Fosazepam Fact Sheet: Risks, Uses, & Alternative Options

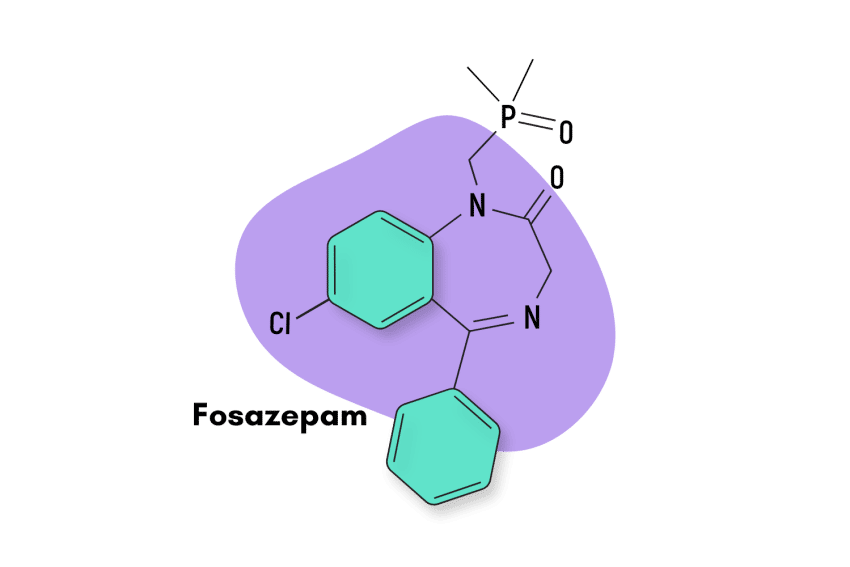

Fosazepam is a chemical derivative of diazepam, a more widely known benzodiazepine sold under the commercial name Valium.

Fosazeman is essentially a water-soluble form of diazepam. It’s created by adding a dimethylphosphoryl group to the original chemical structure of diazepam.

This change was thought to enhance fosazepam’s absorption and make it stronger than diazepam. However, researchers discovered the potency of fosazepam was only 20% as potent as diazepam [2] and about 10% as potent as nitrazepam [1].

This drug is not used much in medicine, but it’s become relatively popular on the designer drug market in recent years. It’s considered a gentler and less sedative form of Valium.

Fosazepam Specs:

| Status: | Approved 💊 |

| Common Dosage: | 2–20 mg |

| PubChem ID: | 37114 |

| CAS# | 35322-07-7 |

IUPAC Name: 7-chloro-1-(dimethylphosphorylmethyl)-5-phenyl-3H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one

Other Names: None

Metabolism: Fosazepam is N-demethylated by CYP3A4 and 2C19 to the active metabolite N-desmethyldiazepam and is hydroxylated by CYP3A4 to the active metabolite temazepam.

Duration of Effects: Long-Acting (12+ hours).

How Does Fosazepam Work?

There are dozens of medications in the benzodiazepines class. Even though there are significant differences between them, they all share a similar mechanism of action, making them effective for treating anxiety and sleep disorders.

When it comes to benzodiazepines, the main mechanism of action comes about through their interactions with gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors — more commonly known as GABA receptors. These are a class of neurotransmitters that have significant inhibitory effects on the central nervous system.

Specifically, benzodiazepines bind to the GABA-A subtype but at a site different from where GABA-A itself binds, producing an “allosteric effect.” This effect increases activity at the GABA receptor site without directly stimulating it. Despite several decades of research, these receptors are still poorly understood [3].

Increased GABA receptor activity heightens the passage of negatively charged chloride ions into the neurons. They become hyperpolarized, making it less likely that the neurons will fire the electrical impulses that send signals throughout your body. With the neurons less likely to “fire,” there is a reduced activity level in the brain and central nervous system. These actions are the primary way benzodiazepines exert their effects on the body.

In simple terms, GABA acts like the brake pedal for the brain. Benzodiazepines activate these brakes, slowing down brain activity. High doses can bring neurological activity almost to a dead stop — causing users to become sedated until the drug wears off.

Fosazepam Pharmacodynamics

The GABA-A receptor is composed of different subunits for which many subsequent subtypes exist. Differences in the activation of these subunits account for the distinct effects profile of each benzodiazepine drug.

For instance, receptors containing the α1 subunit mediate the sedative, anterograde amnesic, and partly anticonvulsive effects of diazepam [4].

Furthermore, research shows that diazepam, and consequently fosazepam, exerts its effects via GABA-A receptors composed of α1βγ2, α2βγ2, α3βγ2, and α5βγ2 subunits [5].

However, a scientific consensus in regard to the precise mechanisms of action is still lacking due to the insufficient amount of high-resolution structural data for this drug-binding site.

Is Fosazepam Safe? Risks & Side-Effects

Benzodiazepines are currently listed as a Schedule IV drug in the United States, which means it does have the potential for misuse, as well as physical dependence, although to a lower degree than drugs listed as Schedule III.

In terms of drug overdoses and overall toxicity, deaths resulting from benzodiazepine use have increased considerably over the last 20 years, although the numbers did plateau after 2010 [6]. A 2020 survey by the CDC showed how, in that year, benzodiazepines were involved in 12,290 deaths in the United States. The NIDA states that in 2020, 16% of overdose deaths involving opioids also contained the presence of benzodiazepines.

In response to these worrying trends, the concomitant use of opioids and benzodiazepines is clearly identified as a significant contraindication. The FDA strongly advises against using this drug combination, as it has the potential to cause respiratory depression, the main cause of death in opiate-related drug overdoses.

However, when benzodiazepines are taken properly, the potential for overdoses and serious side effects is considerably lower.

Side Effects of Fosazepam

The FDA has identified a number of adverse reactions associated with fosazepam.

The most common side effects of fosazepam include the following:

- Drowsiness

- Fatigue

- Muscle weakness

- Ataxia

The following side effects have also been reported (rare):

- Antegrade amnesia

- Blurred vision

- Confusion

- Constipation

- Depression

- Dizziness

- Dry mouth

- Dysarthria

- Hallucinations

- Headaches

- Hypotension

- Irritability

- Nausea

- Skin reactions

- Slurred speech

- Tremors

- Vertigo

Benzodiazepine Withdrawal & Dependence

Fosazepam is generally regarded as safe — but addiction and overdoses are always a risk for benzodiazepine drugs, especially among those using the drug off-label or without a doctor’s oversight.

Research shows about one-third of individuals who take benzodiazepines for longer than four weeks become dependent and experience withdrawal symptoms upon cessation [7]. For this reason, benzodiazepine use is generally recommended for the shortest possible time, with a slow-tapered cessation to manage withdrawal symptoms.

In general, the more a drug is consumed, the higher the chance of dependence and withdrawal symptoms. The withdrawal symptoms related to benzodiazepines are comparable to those of alcohol and barbiturates and can be deadly [8].

Fosazepam is a double-edged sword when it comes to dependence and withdrawal. It produces the metabolite nordiazepam, which has a long elimination half-life. This means that daily fosazepam use leads to an increased buildup of this metabolite and an increased potential for addiction. However, fosazepam’s long-elimination half-life also makes it a prime candidate for drug tapering since it can reduce benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.

Fosazepam use should be weighed against the potential of developing dependence. The process of drug tapering is a slow process that usually takes 14-28 weeks. It is safe when conducted appropriately, but complications can develop.

Harm Reduction: Fosazepam

Benzodiazepines carry a high risk of abuse — here are some tips to stay safe and minimize the harm caused by this drug class.

Some tips and tricks for staying safe while taking benzodiazepines like fosazepam:

- 🥣 Don’t mix — Mixing benzodiazepines with other depressants (alcohol, GHB, phenibut, barbiturates, opiates) can be fatal.

- ⏳ Take frequent breaks or plan for a short treatment span — Benzodiazepines can form dependence quickly, so it’s important to stop using the drug periodically.

- 🥄 Always stick to the proper dose — The dosage of benzos can vary substantially. Some drugs require 20 or 30 mg; others can be fatal in doses as low as 3 mg.

- 💊 Be aware of contraindications — Benzodiazepines are significantly more dangerous in older people or those with certain medical conditions.

- 🧪 Test your drugs — If ordering benzos from unregistered vendors (online or street vendors), order a benzo test kit to ensure your pills contain what you think they do.

- 💉 Never snort or inject benzos — Not only does this provide no advantage, but it’s also extremely dangerous. Benzos should be taken orally.

- 🌧 Recognize the signs of addiction — Early warning signs are feeling like you’re not “yourself” without the drug or hiding your habits from loved ones.

- ⚖️ Understand the laws where you live — In most parts of the world, benzodiazepines are only considered legal if given a prescription by a medical doctor.

- 📞 Know where to go if you need help — Help is available for benzodiazepine addiction; you just have to ask for it. Look up “addiction hotline” for more information where you live. (USA: 1-800-662-4357; Canada: 1-866-585-0445; UK: 0300-999-1212).

Avoid Long-Term Use (Take Breaks)

It’s wise to limit benzodiazepine use to the shortest time frame possible, which reduces the potential for harmful effects. In this sense, only use benzodiazepine when a situation is acute enough to warrant it.

Long-term benzodiazepine use carries considerable risk, so seek alternative treatment options that can be used long-term and without risk. For example, therapy or other behavior-oriented solutions and non-pharmacological medications can be very effective.

Drug Interactions to Avoid

Users must also be aware of dangerous drug interactions — alcohol, GHB, phenibut, and opiates almost invariably raise risk levels.

Fosazepam is metabolized by the CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 enzymes in the liver, so other medications that affect these enzymes can interact with fosazepam. The effects of these interactions are unpredictable and are best avoided.

Contraindications

It’s also important to know the characteristics of the specific benzodiazepine. Some benzodiazepines can cause problems when used by people with specific health conditions. For instance, fosazepam’s long elimination half-life makes it a poor candidate for sleep-related issues compared to other benzodiazepines.

All benzos are considered unsafe for people who suffer from myasthenia gravis, sleep apnea, bronchitis, COPD, or major depression. The risk of side effects also increases substantially in older adults (65+).

Fosazepam Dosage

What is the proper fosazepam dosage for each indication?

According to the Mayo Clinic, the approved dosages for each of the indications related to fosazepam include the following:

For anxiety:

- Adults —2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 2 to 4 times a day

- Older adults — At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed.

- Children 6 months of age and older — At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed

- Children up to 6 months of age — Use is not recommended

For alcohol withdrawal:

- Adults — 10 milligrams (mg) 3 or 4 times for the first 24 hours, then 5 mg 3 to 4 times per day as needed

- Older adults — At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor will gradually increase your dose as needed

- Children — Use and dose must be determined by your doctor

For muscle spasms:

- Adults — 2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 3 or 4 times a day

- Older adults — At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed.

- Children 6 months of age and older — At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed

- Children up to 6 months of age — Use is not recommended

For seizures:

- Adults — 2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 2 to 4 times a day

- Older adults — At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed.

- Children 6 months of age and older — At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed.

- Children up to 6 months of age — Use is not recommended.

Similar Benzodiazepines

Fosazepam is classified as a long-acting 1,4-benzodiazepine derivative. Other compounds with the same characteristics include chlordiazepoxide (Librium), clorazepate (Tranxene), halazepam (Paxipam), ketazolam (Anseren), medazepam (Azepamid), phenazepam (Phenazepam), quazepam (Doral), and others.

The closest alternative to fosazepam is diazepam (Valium), and noridazepam (Nordaz).

Other popular benzodiazepines with similar effects include alprazolam (Xanax), bromazepam (Lectopam), clonazepam (Klonopin), and lorazepam (Ativan).

Natural Alternatives to Benzodiazepines

For those that don’t want to take their chances risking adverse effects and physical dependence on benzodiazepines, there are some pretty good herbal options worth considering.

One of the main options is the kava plant (Piper methysticum).

Kava hails from the pacific islands and carries a variety of psychoactive properties that are similar to benzodiazepines. The active ingredients, called the kavalactones, share very similar GABAergic effects and are useful for managing the same conditions (anxiety, insomnia, muscle tension) [9].

Another herbal alternative to benzodiazepines is the kratom plant (Mitragyna speciosa). Kratom has recently been involved in controversy due to its malignment by biased health agencies, but the fact of the matter is that it’s a much safer alternative to benzodiazepines.

Kratom doesn’t offer the same mechanism of action through the GABA receptors. Instead, active alkaloids in kratom, such as mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, work by downregulating neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. The end result is a similar sense of calmness and relaxation experienced after taking benzodiazepines.

Kratom produces anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) and sedative effects in mid-to-high doses and has a limited risk potential when properly used [10]. However, kratom consumption can still cause dependence and is unsafe when mixed with other nervous system depressants like opioids or alcohol.

Fosazepam FAQs

1. Who should avoid taking fosazepam?

According to the FDA, fosazepam is contraindicated in the following situations:

- Patients with a known hypersensitivity to fosazepam

- Patients under six months of age

- Myasthenia gravis

- Severe respiratory insufficiency

- Severe hepatic insufficiency

- Sleep apnea

- Acute narrow-angle glaucoma

It may be used in patients with open-angle glaucoma who are receiving appropriate therapy.

Also, there’s an increased risk of congenital malformations and other developmental abnormalities associated with benzodiazepine drugs during pregnancy.

2. Does food affect fosazepam’s absorption?

The FDA has stated that after oral administration,>90% of diazepam is absorbed, and the average time to achieve peak plasma concentrations is 1 – 1.5 hours, with a range of 0.25 to 2.5 hours.

Absorption is delayed and decreased when administered with a moderate-fat meal. In the presence of food, mean lag times are approximately 45 minutes compared to 15 minutes when fasting. Additionally, there is also an increase in the average time to achieve peak concentrations to about 2.5 hours in the presence of food compared with 1.25 hours when fasting.

References Used

- Risberg, A. M., Henricsson, S., & Ingvar, D. H. (1977). Evaluation of the effect of Fosazpeam (a new benzodiazepine), nitrazepam and placebo on sleep patterns in normal subjects. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 12(2), 105-109.

- Nicholson, A. N., Stone, B. M., & Clarke, C. H. (1976). Effect of diazepam and fosazepam (a soluble derivative of diazepam) on sleep in man. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 3(4), 533-541.

- Campo‐Soria, C., Chang, Y., & Weiss, D. S. (2006). Mechanism of action of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors. British journal of pharmacology, 148(7), 984-990.

- Sieghart, W., & Sperk, G. (2002). Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABA-A receptor subtypes. Current topics in medicinal chemistry, 2(8), 795-816.

- Richter, L., De Graaf, C., Sieghart, W., Varagic, Z., Mörzinger, M., De Esch, I. J., … & Ernst, M. (2012). Diazepam-bound GABAA receptor models identify new benzodiazepine binding-site ligands. Nature chemical biology, 8(5), 455-464.

- Bachhuber, M. A., Hennessy, S., Cunningham, C. O., & Starrels, J. L. (2016). Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996–2013. American journal of public health, 106(4), 686-688.

- Riss, J., Cloyd, J., Gates, J., & Collins, S. (2008). Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Acta neurologica scandinavica, 118(2), 69-86.

- Sachdeva, A., Choudhary, M., & Chandra, M. (2015). Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: benzodiazepines and beyond. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 9(9), VE01.

- Cairney, S., Clough, A. R., Maruff, P., Collie, A., Currie, B. J., & Currie, J. (2003). Saccade and cognitive function in chronic kava users. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(2), 389-396.

- Swogger, M. T., & Walsh, Z. (2018). Kratom use and mental health: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 134-140.