Understanding Psilocybin: A Comprehensive Look at the Psychedelic Substance

Psilocin brings life to the party 🕺 while psilocybin provides stability 🤓 Together, they make an unbeatable duo.

We have likely been consuming magic mushrooms before we evolved into modern humans. Today we use them as a tool for self-growth, introspection, healing, recreation, and more.

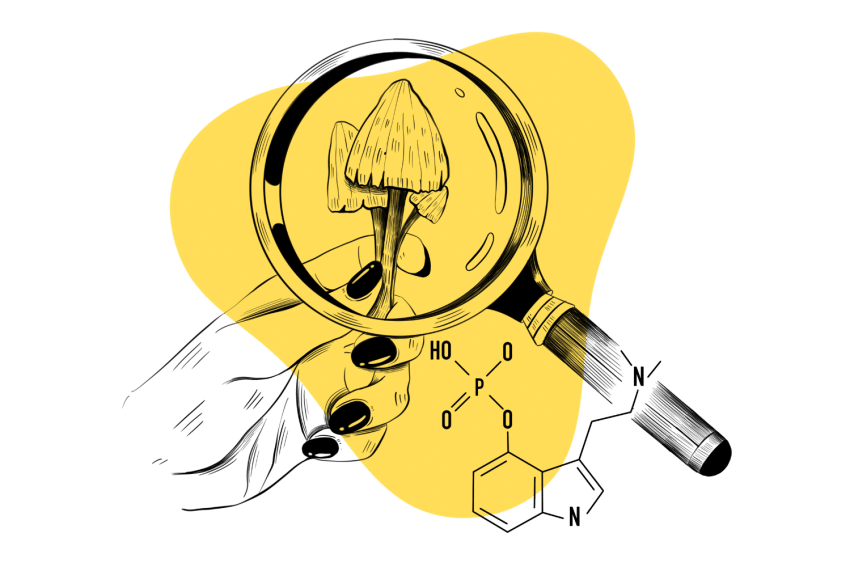

The active components in these mushrooms are a set of indole alkaloids called psilocybin and psilocin.

Most of the research today focuses on the more abundant of the two — psilocybin.

Here’s what we know so far.

What Is Psilocybin?

Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-NN-dimethyltryptamine) is one of the active ingredients in “magic mushrooms.” While it’s the compound people typically discuss, it’s not psychedelic or intoxicating on its own.

Psilocybin rapidly converts to psilocin after passing through the liver — which is the compound responsible for the psychedelic effects.

Psilocybin is a “pro-drug,” an inactive substance that converts to an active drug after consumption. Once mushrooms go through the liver, the enzymes that help us digest them start quickly dephosphorylating them to get rid of the phosphate group [1].

When this happens, psilocin (4-HO-DMT) can pass through the blood-brain barrier and bind to serotonin (5-HT2A, 2B, and 2C) receptors.

Psilocin may steal the show when it comes to effects, but it’s extremely unstable [2]. It breaks down quickly and accounts for only a small percentage of dried magic mushrooms.

Psilocybin, on the other hand, offers stability to the mushroom and ensures it remains potent for a long time.

When magic mushrooms are touched, they bruise a blue color. This is one of the distinguishing features of these mushrooms while hunting them in the wild. In his book Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World, Paul Stamets theorizes that the blue color comes from the oxidation of psilocin [3].

If this were the case, the bruising would likely indicate a loss of potency as the psilocin oxidizes and forms a bluish hue.

Far more prominent is psilocybin, a stable compound that reliably converts to psilocin after consumption.

Tripsitter Psilocybin Safe-Trip Checklist

Before taking psychedelics, it’s important to know the risks associated with the substance you intend to use. While psilocybin-containing mushrooms are considered one of the safest drugs available, they aren’t completely devoid of risk.

Use the below checklist to minimize the risks of tripping with psilocybin-containing mushrooms:

- 🐍 I understand why psychedelics should be treated with respect

- ⚖️ I’m familiar with the laws for psilocybin-containing mushrooms in my country & state

- 🍄 I’m familiar with and confident in the dose I’m taking (1–3 g for the first session)

- 💊 I’m not mixing any medications or other substances with magic mushrooms

- 🏔 I’m in a safe & comfortable environment with people I trust

- 🐺 One of the members of my group is responsible and sober (AKA a trip sitter)

- ⏳ I have nothing important scheduled for after the trip

- 🧠 I’m in a sound & healthy state of mind

- 📚 I’m familiar with the four pillars of responsible psychedelic use — set, setting, sitter, & substance.

- 🍄 I’ve properly identified the mushrooms I’m using — never wildcraft psilocybin mushrooms unless you’re 100% sure about the species you’re picking. There are poisonous lookalikes.

- ⏳ Know the timeline — the effects of magic mushrooms are going to last between 6 and 8 hours.

- 🙅♀️ Know when to avoid magic mushrooms — don’t take shrooms if you have underlying cardiovascular, neurological, or psychiatric disorders.

Note: These tips can’t ensure you will have a good experience, but it goes a long way in helping. Bad trips can happen to anyone, but they’re much less likely with a little preparation.

Scientific Research: Psilocybin

Psilocybin is widely studied. It’s currently being explored as a treatment for depression, existential anxiety, addiction, cluster headaches, and more.

Of the many different possible applications, these are the current most promising areas of research:

1. Psilocybin & Treatment-Resistant Depression

Depression is a major concern in modern society and has been for some time — even if we haven’t always had the right words for it. You might be surprised to hear how often we are unable to treat these conditions.

According to research, as many as two-thirds of all patients diagnosed with depression will not find success in their first treatment. Another third will not find remission from any current treatments for depression [4].

While we’ve never had a solution for this before, psychedelics are showing significant potential to help with depression. A study involving two psilocybin sessions with 24 participants found that 17 of them reported significant reductions in depression scores after four weeks [5].

Despite having previously failed to find effective treatment, 13 participants met the criteria for depression remission. The participant size was small, but their conditions were severe, making the results very promising.

Learn More: Medicine for the Mind — Psychedelics for Depression & Mental Health

2. Psilocybin & Existential Anxiety

Existential anxiety is a type of anxiety that arises from thoughts and concerns about the meaning and purpose of life, death, and one’s place in the world. It’s common among people who receive a terminal diagnosis (or recently recovered from a life-threatening injury or illness).

A 2016 study involving 29 subjects facing life-threatening forms of cancer found the potential for easing the existential anxiety they felt [6]. This was a “crossover” study, meaning patients received both a placebo and an active dose.

The result was “immediate, substantial, and sustained … clinical benefits” despite the incredible levels of anxiety the patients must have felt. Existential anxiety and the fear of death itself were the baselines for this group of participants — of whom 58% saw reduced anxiety compared to 14% with the placebo.

Researchers saw a 60–80% success rate at the 6.5-month follow-up, showing the results were long-term.

Learn More: Shrooms for Existential Anxiety & End-of-Life Care

3. Psilocybin & Addiction

Nicotine — the addictive substance in tobacco — is one of the most likely substances to lead to dependence. A study from 2014 found it was more addictive than cocaine, alcohol, and cannabis [7].

In the study, researchers found 67.5% of smokers became dependent, as opposed to under 21% of cocaine users (the next highest group).

In another study, researchers aimed to look at the effects of psilocybin on nicotine addiction [8]. Preliminary findings involving 15 participants found that 12 of them (80%) were abstinent from tobacco after a six-month follow-up. These results are substantial, considering fewer than 10% of smokers are successful at quitting each year, according to the CDC.

Despite promising results, studies are slow to follow up on this. Hopefully, this changes in the future, and the full potential of this treatment can come to light.

Learn More: How Psychedelics Are Reinventing Addiction Therapy

4. Psilocybin & Cluster Headaches

Cluster headaches — painful headaches occurring in cyclical or episodic patterns — are likely the most painful type of headache. While a few treatments have shown a small amount of success in treating the symptoms of cluster headaches, most sufferers are unsuccessful in stopping them completely.

Psilocybin and the related tryptamine, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), have shown significant promise for this elusive condition.

A small study conducted in 2012 interviewed 53 patients who claimed to have used psilocybin and LSD to treat cluster headaches. Before discussing results, there’s an important distinction between this and the other research discussed above — this study only involves people who personally reached out to researchers.

This means there is likely a bias since participants with success stories are more likely to be vocal about it.

Still, of the 22 respondents, 20 of them reported psilocybin as effective for “treatments for cluster attacks, cluster periods, and remission extension” [9]. That makes psilocybin — and/or other psychedelic drugs — a potential breakthrough treatment for cluster headaches.

Despite the inherent problems with this review, hopefully, it will lead to more robust research in the future.

Learn More: Psilocybin for Cluster Headaches

What to Expect from Psilocybin

The effects of magic mushrooms depend a lot on how much you take, and even a minute increase makes a big difference in the effects.

There are four main “categories” for dosage size that people often refer to:

Here’s what to expect from psilocybin based on how much you consume in dried mushrooms or pure psilocybin.

1. Microdose

(2–5 mg psilocybin)

Microdoses are, by definition, sub-perceptual — meaning you don’t notice the effects. While this amount won’t make you “trip,” many claim they experience several benefits.

Whether this is true or not is still uncertain; individual reports are very positive, but scientific research remains more uncertain. The frequency varies but typically involves multiple doses per week on alternating schedules.

A microdose of psilocybin is around 2–5 mg — which works out to roughly 0.2–0.5 grams of dried Psilocybe cubensis (depending on the strain).

Reported benefits of microdosing psilocybin include [10]:

- Improved cognition

- Increased energy

- Feelings of connectivity

- Higher overall wellbeing

- Boosted Productivity

- Elevated happiness

There are relatively few risks associated with microdosing psilocybin, and the effects can be beautiful. However, even if microdosing is beneficial, try interspersing some larger doses here and there.

2. Threshold Dose

(5-10 mg psilocybin)

A threshold dose refers to the minimum amount of a substance needed for users to notice their effects. Also known as “museum doses,” a threshold dose is used to alter perception and induce visual effects without being too strong physically. It’s also a useful metric for assessing the safe dose of a substance. Whenever trying something new, it’s wise to take the threshold dose first to get a feel for its effects before going deeper.

A threshold dose of psilocybin is around 5–10 mg — which works out to roughly 0.5–1 gram of dried Psilocybe cubensis.

Threshold doses are used to enhance creativity, boost mood, and increase a sense of empathy without a heavy body load. Due to psilocybin’s ability to quickly build up a tolerance in your system, the threshold dose increases every day you take it. Tolerance reverses after about a week of no use.

3. Standard Psychoactive Dose

(20–50 mg psilocybin)

The standard psychoactive dose refers to the common dose used by people who intend to experience the full effects of a substance.

This is the “sweet spot” for most psychonauts — strong enough to lead to a complete psychedelic experience.

Full doses of psilocybin cause visual and auditory hallucinations and heavy introspection and facilitate self-exploration. As far as the effect on the body, this amount can feel quite heavy — resulting in difficulty moving, nausea (especially at the beginning of the trip), and poor coordination.

A standard psychoactive dose of psilocybin is around 20 to 50 mg — which works out to around 1–3 grams of dried Psilocybe cubensis.

It’s important to be conservative when using mushrooms for the first time. Even the difference between 1 or 2 mg is substantial.

4. Heroic Dose

(50+ mg pure psilocybin)

A heroic dose refers to a very large dose taken with the desire to achieve a mystical experience.

Terence McKenna was a proponent of this dosage and would take it a step further by isolating himself in a quiet, dark room.

I’ll let his own words speak for its power and the caution you should take:

Experimenters should be very careful. One must build up to the experience. These are bizarre dimensions of extraordinary power and beauty. There is no set rule to avoid being overwhelmed, but move carefully, reflect a great deal, and always try to map experiences back onto the history of the race and the philosophical and religious accomplishments of the species. All the compounds are potentially dangerous, and all compounds, at sufficient doses or repeated over time, involve risks. The library is the first place to go when looking into taking a new compound.

A heroic dose of psilocybin is around 50 mg or higher — which works out to 5 g or more of dried Psilocybe cubensis.

Due to the intense experience induced by this kind of dose, we always recommend having a trained professional nearby — or, at the very least, a responsible, trusted trip sitter. This is a dose you should reserve for once or twice a year at most.

Is Psilocybin Safe?

Psilocybin has an incredible safety profile and is very unlikely to lead to serious problems or death, regardless of dosage. The LD50 of psilocybin — or the amount it would take to kill half of the people who ingest it — comes out to around 280 mg per kilogram of your weight [11].

On average, this would equate to ingesting around 17 kg (~37.5 lbs) of mushrooms. This renders it basically impossible since your body would metabolize and pass the mushrooms you start with long before finishing the rest.

Researchers often determine safety by comparing the amount you need to feel its effects to the amount you need to die from it. Using 2 g of dried mushrooms as a baseline, you would have to consume roughly 8,500x the standard dose to die from it.

Even trying to consume pure psilocybin would be difficult — a 170-pound person would need to consume 21.5 g of the powder (roughly ¾ oz) to reach this limit.

While psilocybin is physically safe, it isn’t without its risks. The main concern when it comes to hallucinogenic experiences centers around the psychological effects, as opposed to the physical ones.

Psilocybin & Psychological Concerns

The psychedelic experience calls you to explore every corner of your mind — sometimes, these corners can get quite dark. It is not uncommon to contemplate horrific or depressing things while tripping on psychedelics.

Related: What is the Shadow & Why Should I Seek to Confront It?

It’s common for people to go into a trip without the proper precautions or expectations and find themselves overwhelmed and frightened.

Regardless of how long the trip lasts, time-dilation effects can make each minute feel like several hours. Having a trip sitter nearby to help you work through these difficult emotions can change the course of your trip and bring good out of it.

If you’re alone and feel a bad thought coming on, don’t ignore it: try to face it, learn from it, and see if you can grow because of it. It may seem scary, but it’s much less frightening than spending the entire time trying to hide from your own mind.

One major concern for people with psychological conditions such as schizophrenia is that hallucinogens could trigger an episode.

In rare instances, some people experience a condition called HPPD (hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder). With this condition, users experience lasting visual or auditory hallucinations weeks or months after taking the psychedelic.

How Long Does Psilocybin Last In Your System?

Psilocybin kicks in within about 45 minutes and lasts about six or seven hours. It then remains detectable in the system (as psilocin) for around 24 hours.

Psilocybin itself doesn’t stay in the system long since our body rapidly metabolizes it into other compounds. It’s almost immediately converted to psilocin. Therefore, psilocin is the main compound researchers test for when conducting studies on magic mushrooms [12]. However, they must do so very carefully since psilocin degrades very quickly too.

When checking for psilocybin or psilocin in urine, scientists must flash-preserve the urine right away. Most people excrete all the psilocin from their system within about 24 hours.

Some suggest psilocin could stay within hair follicles for up to 90 days after ingestion, but these types of tests are rare and unreliable. Blood and saliva tests are not possible for magic mushrooms since they metabolize too quickly.

As far as psilocybin’s effects go, users can expect to be back to their baseline state within 8 hours. There may be some lingering “afterglow” effects lasting another 12–24 hours, but the “trip” is essentially over at this point.

The History of Psilocybin Use

Humans have been using mushrooms for religious and recreational reasons for thousands of years — some scientists believe our prehistoric ancestors ate these mushrooms too — making the use of magic mushrooms older than humanity itself.

Let’s take a trip through time and see how psilocybin has impacted cultures.

The Stoned Ape Theory: Psilocybin & Brain Expansion in Early Primates

It seems likely humanoid ancestors were using psilocybin-containing mushrooms long before we became Homo sapiens sapiens. Credit for popularizing this theory goes to Terrance McKenna, who coined it “The Stoned Ape Theory.”

He postulated that early human ancestors were forced from their trees and largely fruitarian lifestyles during the Pliocene Epoch. This is a time of global temperature fluctuation, changing the environment our tree-dwelling evolutionary ancestors had adapted to over such a long period.

As vegetation diversified and forests gradually morphed into grasslands, our primate ancestors were forced to descend from the trees. Hominins — these ape-like ancestors — had to change their diet as a result. One of the foods they were believed to consume was psilocybin-containing mushrooms, which grew readily out of the dung of grazing animals living in the grasslands.

Over time, the consumption of mind-expanding mushrooms among these early primates was believed to contribute to the sudden expansion of the brain roughly 3 million years ago. This enlargement of the neocortex of the primate brain is what allowed for the invention of art, language, culture, and more.

Research on Psilocybin & Human Evolution

While McKenna was likely starry-eyed in his approach, he’s not alone in his thinking. As one report on evolution and psychedelics puts it [13]:

We recognize that a simplistic version of McKenna’s account of human evolution implying that psilocybin use by itself led inevitably to the emergence of the unique cognitive, communicative, and cooperative patterns characteristic of modern human populations is most certainly false. Hominin entry into the socio-cognitive niche cannot be explained in terms of a single causal factor, a critical adaptive breakthrough (e.g., bipedality, tool-use, cooking, or even psychedelic use), but instead through positive feedback loops among various aspects of hominin life, an adaptive complex involving novel or greatly exaggerated features of our lineage (Sterelny, 2012). From this multifactorial and coevolutionary viewpoint, we propose psychedelics acted as an enabling factor in human adaptation and evolution (emphasis theirs).

While psychedelic mushrooms were unlikely the sole contributor to this change, it’s possible they contributed to it. The idea seems more likely when you pair this with the fact that 22 other primates eat mushrooms [14], and so did early humans in the Paleolithic period directly after the Pliocene Epoch [15].

Indigenous & Traditional Psilocybin Use

Nearly every corner of the world has a history of psilocybin-containing mushrooms, especially the regions around Central and South America where these mushrooms were abundant.

For example, the Aztec culture revered these mushrooms, honoring them with the name Teonanácatl, or “flesh of god.”

While this may be the most popular location for magic mushroom use, it’s far from the only one. Evidence exists for use in the ancient societies of Greece, Egypt, Australia, Southeast Asia, and more.

Common traditional uses of magic mushrooms around the world include:

- For spiritual growth

- For self-examination & reflection

- For the treatment of psychiatric conditions & other diseases

- For ceremonial use

Unfortunately, brutal colonization efforts destroyed much of what we know about the exact context in which psilocybin-containing mushrooms were used throughout history.

Modern History of Psilocybin

In 1957, when R. Gordon Wasson and his crew finally found the mushrooms in Mexico after four summers of searching, he mentioned the Christian intermingling in the ceremony [16]. He states, “The [Indigenous peoples] mingled Christian and pre-Christian elements in their religious practices in a way disconcerting for Christians but natural for them.”

The write-up of his experience for Life Magazine — the biggest publication at the time — effectively unleashed the mushroom on America. He even included diagrams to identify the psychedelic mushrooms, which many used as early “field guides” for seeking the mushroom on their own.

He went on to state how they were “the first white men in recorded history to eat the divine mushrooms, which for centuries have been a secret of certain [indigenous] peoples living far from the great world in southern Mexico.”

Shortly after Wasson brought the mushroom samples back, Albert Hofmann — the inventor of LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) — isolated the compounds responsible for the effects.

Today, as a result of these efforts, along with the work of early pioneers like Timothy Leary, Alexander Shulgin, Terence McKenna, Dennis McKenna, Richard Alpert, and countless others, we’ve been given a glimpse at their incredible therapeutic potential.

The Effects of Psilocybin Popularization on Indigenous Communities

Tragically, the biggest victims of this movement are the indigenous communities that took a risk by opening up their spirituality to the world. Maria Sabina, the curandera — or mushroom healer — who introduced Wasson to the mushroom, famously came to regret doing so.

After the profile on Sabina by Wasson, her city became a tourist destination for psychotourists who often had little interest in the mushroom’s spirituality. Her community would go on to shun her, burn her home down, murder her son, and briefly jail her.

She died in poverty at the age of 95, despite worldwide fame and after leading numerous ceremonies for high-profile celebrities.

How Does Psilocybin Compare to Other Drugs?

Psilocybin is characterized as an indole alkaloid (indolealkylamine) and tryptamine — which makes it most closely related to psychedelics like LSD (and other lysergamides), DMT analogs, DiPT analogs, ibogaine, and the harmala alkaloids.

In terms of effects, psilocybin is most comparable to psilocin (which is the active metabolite) and 4-AcO-DMT (which is another pro-drug of psilocin). The effects are also very similar to LSD and the rest of the lysergamides family, albeit shorter-lasting and with a slightly stronger body load.

Psilocybin is also comparable in effects to the phenethylamine psychedelics, such as mescaline or various 2CX compounds.

Psilocybin is not comparable to the dissociative classes (such as the arylcyclohexylamines) or amphetamine psychedelics like MDMA.

One of the biggest differences between psilocybin and other conventional psychedelics comes down to something completely separate from its chemical structure or effect profile. What makes psilocybin unique is how easy it is to produce at home.

You can easily grow psilocybin-containing mushrooms at home with little cost or care. Most other psychedelics require chemistry know-how and access to a lab. Mescaline can also be obtained naturally, but growing San Pedro or peyote cactus takes significantly more time and effort.

Psilocybin vs. LSD

The effects of psilocybin are very similar to LSD — but with some key differences.

Psilocybin tends to have a stronger effect on the body than LSD and doesn’t last as long. It can feel heavier, produce more tactile trippiness, and can cause some users to feel a bit nauseous. LSD tends to be lighter and more “clear” feeling overall.

In terms of duration of effects, psilocybin lasts around 5-7 hours (8 hours max), and LSD remains active for around 6–8 hours (10 hours max).

| Metrics | Psilocybin | LSD |

| Chemical Class | Tryptamine | Tryptamine |

| Natural or Synthetic? | Natural | Semi-Synthetic |

| Duration of Effects | 5–7 hours | 6–8 hours |

| Common Dose | 20–50 mg | 80–160 mcg |

Psilocybin vs. MDMA

MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is classified as an amphetamine, which makes it very different from a structural perspective. MDMA is much more stimulating than psilocybin, lending itself more to the party or rave scene than the more individual exploration people engage in with magic mushrooms.

Psilocybin is a much stronger hallucinogen than MDMA overall — but MDMA does activate similar receptors (5-HT2C) and is technically classified as a hallucinogen.

MDMA, by contrast, acts primarily as an “empathogen,” meaning it brings about feelings of love and empathy.

| Metrics | Psilocybin | MDMA |

| Chemical Class | Tryptamine | Amphetamine |

| Natural or Synthetic? | Natural | Synthetic |

| Duration of Effects | 5–7 hours | 4–6 hours |

| Common Dose | 20–50 mg | 50–150 mg |

Psilocybin vs. DMT

There are a few substances people refer to when talking about DMT (dimethyltryptamine) — N,N-DMT is the form found in sources like ayahuasca, while 5-MeO-DMT is the active ingredient in Bufo toad venom. Both are extremely potent psychedelics that act via the 5-HT2C pathway, but the qualitative experience is distinct between them.

In small doses, DMT shares similar qualities to psilocybin — altering visual, auditory, and tactile perception and inducing divergent thought patterns.

In larger doses, DMT and psilocybin are entirely different. High-dose DMT has the capacity to separate the mind from reality entirely — often blasting off into a world of geometric fractals and vivid visions of other places. Psilocybin rarely has this profound of an impact, even in very high doses.

Another major difference between DMT and psilocybin is the duration of action. 5-MeO-DMT lasts roughly 45 minutes total before wearing off completely.

| Metrics | Psilocybin | N,N-DMT | 5-MeO-DMT |

| Chemical Class | Tryptamine | Tryptamine | Tryptamine |

| Natural or Synthetic? | Natural | Natural | Natural |

| Duration of Effects | 5–7 hours | 30–60 minutes Ayahuasca (6–9 hours) | 30–60 minutes |

| Common Dose | 20–50 mg (oral) | 10–25 mg (inhalation) | 5–12 mg (inhalation) |

Psilocybin vs. 4-AcO-DMT

4-AcO-DMT (4-Acetoxy-DMT) is a prodrug for psilocin (4-HO-DMT) just like psilocybin. Therefore, 4-AcO-DMT and psilocybin are almost identical in terms of effects. The only major difference between the two is the onset time — which is about 20% longer with 4-AcO-DMT compared to psilocybin.

Another difference between these two compounds is their legal status. 4-AcO-DMT is a newer, synthetic molecule and isn’t always included on the restricted substances list. For example, you can buy 4-AcO-DMT fairly easily in places like Canada that don’t have analog laws to preemptively ban newer psychedelic lookalikes.

| Metrics | Psilocybin | LSD |

| Chemical Class | Tryptamine | Tryptamine |

| Natural or Synthetic? | Natural | Synthetic |

| Duration of Effects | 5–7 hours | 2–6 hours |

| Common Dose | 20–50 mg | 20–30 mg |

References

- Gotvaldová, K., Hájková, K., Borovička, J., Jurok, R., Cihlářová, P., & Kuchař, M. (2021). Stability of psilocybin and its four analogs in the biomass of the psychotropic mushroom Psilocybe cubensis. Drug testing and analysis, 13(2), 439-446.

- Stamets, P. (1996). Psilocybin mushrooms of the world. Ten Speed Press.

- Lenz, C., Dörner, S., Trottmann, F., Hertweck, C., Sherwood, A., & Hoffmeister, D. (2022). Assessment of Bioactivity‐Modulating Pseudo‐Ring Formation in Psilocin and Related Tryptamines. ChemBioChem.

- Ionescu, D. F., Rosenbaum, J. F., & Alpert, J. E. (2022). Pharmacological approaches to the challenge of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience.

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., May, D. G., Cosimano, M. P., Sepeda, N. D., Johnson, M. W., … & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 78(5), 481-489.

- Ross, S., Bossis, A., Guss, J., Agin-Liebes, G., Malone, T., Cohen, B., … & Schmidt, B. L. (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1165-1180.

- Lopez-Quintero, C., de los Cobos, J. P., Hasin, D. S., Okuda, M., Wang, S., Grant, B. F., & Blanco, C. (2011). Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug and alcohol dependence, 115(1-2), 120-130.

- Garcia-Romeu, A., R Griffiths, R., & W Johnson, M. (2014). Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Current drug abuse reviews, 7(3), 157-164.

- Sewell, R. A., Halpern, J. H., & Pope, H. G. (2006). Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. Neurology, 66(12), 1920-1922.

- Polito, V., & Stevenson, R. J. (2019). A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PloS one, 14(2), e0211023.

- Daniel, J., & Haberman, M. (2017). Clinical potential of psilocybin as a treatment for mental health conditions. Mental Health Clinician, 7(1), 24-28.

- Hasler, F., Bourquin, D., Brenneisen, R., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2002). Renal excretion profiles of psilocin following oral administration of psilocybin: a controlled study in man. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis, 30(2), 331-339.

- Arce, J. M. R., & Winkelman, M. J. (2021). Psychedelics, Sociality, and Human Evolution. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

- Hanson, A. M., Hodge, K. T., & Porter, L. M. (2003). Mycophagy among primates. Mycologist, 17(1), 6-10.

- O’Regan, H. J., Lamb, A. L., & Wilkinson, D. M. (2016). The missing mushrooms: Searching for fungi in ancient human dietary analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 75, 139-143.

- Wasson, R. G. (1957). Seeking the magic mushroom. Life, 42(19), 100-120.