Lessons From Portugal: Decriminalization in Action

Portugal decriminalized the personal possession, use, and acquisition of all drugs in 2001. What are the results? Did it go far enough?

It was my first day in Lisbon, and I was hoping that I could rustle up some of the famous Portugal hashish I had been reading about. Walking down a moderately-trafficked staircase (the one pictured below) in a public area, I saw three men smoking out of a metal pipe and began approaching them.

It was only after I had already asked them if I could “buy some of what they were smoking” that I realized the product in their baggies was white. While I recognized that I probably wasn’t interested in partaking in what they had, it made me happy to see them there. These men weren’t holed away in some alley or dark home; they were in public, in the daytime, unafraid.

Portugal decriminalized all drugs in 2001 and has sought a humanely-focused drug treatment since. To that end, the possession, acquisition, and use of personal quantities of all drugs are now effectively ‘legal’ and have been for over 20 years.

There are many ways that this has been helpful, but there are still a few areas in which it has not gone far enough.

The Positive Side of Decriminalization in Portugal

The idea that the best way to control drugs is to not punish people for using them flies in the face of most drug policies worldwide. Even after looking at the successful elements of Portugal’s humanitarian policy, I have heard excuse after excuse for why it works “there, but not here.”

To be clear, Portugal’s drug policy is far from perfect and represents only a fraction of what many advocates would like to see. That said, a small win is a win nonetheless. While the approach has often fallen short, the fact that they made such a radical choice was outstanding, and they have seen plenty of positive outcomes.

Decriminaliztion’s Effect on Needle-Born Illness

Portugal first launched their needle exchange program back in 1993, and its popularity and ease of use have grown since. In 2017, pharmacies and other needle exchange centers traded out 1.4m needles [1].

When they first instituted their policies of harm reduction, Portugal had one of the highest rates of HIV infection in Western Europe. The needle exchange program “Say No to a Second-Hand Syringe” in Portugal drastically lowered this and had massive health implications.

Some estimates state that the program saves the country an average of €3.01 per syringe exchanged [2]. An external evaluation in 2002 concluded that the program had avoided 7,000 new HIV infections per 10,000 injecting drug users at that time [3].

The public should view needle exchanges as one of the least radical ways to combat needle-born illness. The connection between a person’s ability to obtain a clean needle without fear and the risk associated with injecting with used needles is an obvious one.

Giving clean needles to people who need them doesn’t encourage drug use. Rest assured, the desire for drug use was present long before the clean needle came to them.

Easy, non-intimidating access to clean needles should be a right that humans have at this point. Especially if the argument is that addiction is a disease that the user cannot help. Why, then, would we not provide them the tools they need while they tend to their “disease?”

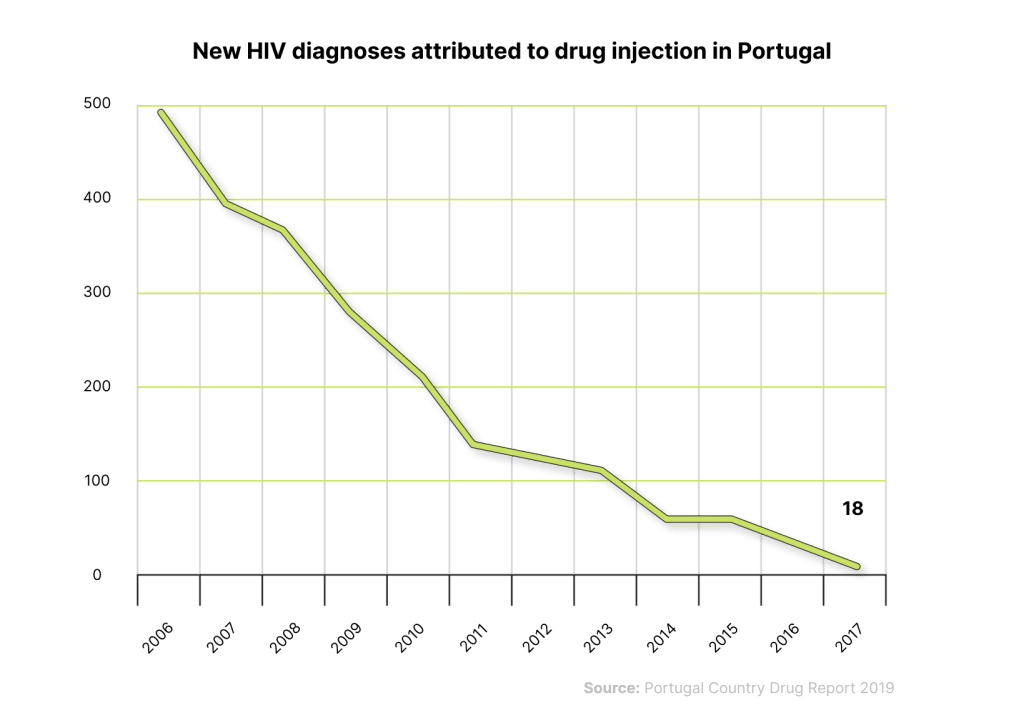

The following graph shows the decreasing trend in the number of new HIV diagnoses attributed to drug injections in Portugal from 2006 to 2017 [1].

In 2017, 13% of drug users who had ever injected drugs and who were tested at outpatient treatment services were HIV positive. In 2011, this number was up 16.48%, and 19.48% in 2010 [3].

Compared to other European Union countries, Portugal had one of the lowest prevalences of new HIV diagnoses related to injecting drug use. The country ranked in place 24 out of 29, with <0.1 HIV-positive people per million population [4].

Decriminalization’s Effect on Use-Disorder

Taking away the taboo on psychoactive substances and encouraging education over indoctrination is the only sympathetic approach to use disorder. The common claim is that removing the penalty for drug use will only encourage others to use more drugs.

The inherent flaw in this argument is that drugs are currently very much illegal, and plenty of people still find encouragement to use them. Cocaine and the illicit amphetamine trade in North America are not slowed by the increasingly stern legislation against it — mostly because the vast majority of drug arrests are for simple possession and have no overall effect on the clandestine market.

Decriminalization seems to reduce the amount that people use drugs as well. The drug use rate of young adults (15-34 years) in Portugal is less than the European average for cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, and amphetamines [1].

This stays true when looking at the lifelong use of drugs. According to the ESPAD 2019 report, 14% of Portuguese students between 15 to 16 years reported drug use in their lifetime; that’s lower than the 16.7% average among all the other European countries [5].

Related: What’s the Difference Between Decriminalization & Legalization?

Where Portugal Falls Short

Twenty years ago, Portugal took a significant step forward in health and human policy. They became the first country to change the focus of their laws so that they were off the user and on the provider.

While removing many of these penalties is great, they fall short of proactively assisting them. Needle exchange programs should be the beginning of a much larger battle. There is still a great deal of harm reduction services that Portugal has promised to deliver but has not followed up on.

In particular, drug-checking assistance and safe injection rooms are still missing from the Portuguese landscape. These two options make it easier to prevent overdose from contamination — one of the largest causes of drug-related deaths.

Another major issue comes with the definition of “personal quantities,” which Portugal calculates to be ten days’ worth of a drug. Each substance has its own quantity that the government deems acceptable for that period.

This limits the freedom of the people who use drugs and have to re-up their supply every ten days. For many, the 10-day limit is far from the amount they use in that time which puts the Portuguese Ministry of Health in the unique position of determining the amount of drugs its citizens can purchase.

Contrasting Portugal with America

In America, minor possession of an illegal substance could ruin your life.

Even minor quantities of the wrong substance can place you on a list for the rest of your life, making it harder to get a job, rent an apartment, or participate in society.

Not only does prison not work as an effective deterrent, but we can’t expect it to act as a de facto detox center. That’s because so many drugs enter the walls of the places where we lock people up for using drugs that we are essentially unable to stop them.

Humans have been using drugs for as long as there have been humans. Perhaps even longer if you buy into the Stoned Ape Theory. Almost every American uses drugs in the form of caffeine or alcohol daily, yet we don’t demonize them for it.

Instead, we choose which substances can shape our society and which ones should lead to jail time. For most, this thought process finds its root in misinformation and genuine concern. Our whole lives, the concept of penalizing away behaviors we don’t like has been the prevailing narrative of drugs.

One thing is sure: criminalization doesn’t help. Drug use is as alive as ever, and the illegal trade of drugs has only gained the ability to demand higher prices. Why keep bulking up the budget on the war on drugs when it has been an abject failure for over 50 years?