What is Rapé (Hapé)? A Guide to Sacred Tobacco

Rapé has been used for thousands of years throughout the Americas, where tobacco is regarded as potent medicine and often reserved for ceremonial use. It’s used by being blown up the nostrils.

Rapé is still produced throughout the Amazon basin to this day, by indigenous groups such as the Yawana, Matse, Huni Kuin, Nukini, Kuntanawa, and many others, with many recipes still kept secret. It’s often part of ceremonial rites of passage in tribes or as part of ayahuasca and Kambo ceremonies, making rapé popular worldwide.

Here, you’ll learn all about rapé, its history, dosing information, health benefits and risks, and much more.

What are the Benefits of Rapé?

From a Western perspective, tobacco is considered a dangerous and addictive vice. However, tobacco is considered a master plant teacher in the Amazon — often used to heal physical and spiritual ailments.

Traditionally, there are many uses of rapé, which can vary greatly geographically, but some common uses are:

- Calming and grounding — to quiet excessive thinking

- Cleansing — to purify the physical & energetic body of negative thoughts or energies

- Guidance — to receive clarity about certain questions or problems

- Expectorant — to clear mucus from sinuses

- Anti-headache — to treat mild to moderate headaches

- Mild euphoric — as a social tool, much like how one might share drinks

- Nootropic — to improve focus & concentration while hunting or working

In the book Plant Teachers, Jeremy Narby outlines a Western scientific perspective of tobacco, exploring why it is seen as a medicine. It’s worth noting that not all rapé contain tobacco, but as it is a common base and because nicotine is perhaps unjustly stigmatized, here are some recent findings about nicotine.

Nicotine, the primary alkaloid in tobacco, resembles the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is involved in everything from learning and memory to voluntary muscle contractions.

Nicotine interacts with the following neurotransmitters:

- Dopamine — Involved in the rewards and pleasure pathways in the brain. It’s believed to play a role in making nicotine addictive [1].

- Glutamate — Associated with learning and new neural connections, and nicotine could have cognitive benefits [2].

- Endorphins — Act as the body’s natural painkillers and induce feelings of pleasure and euphoria [3].

- Epinephrine (Adrenaline) — Involved in the fight or flight (stress) response and inducing a sense of wakefulness and vigilance [4].

Nicotine also shows antimicrobial properties [5]. A report in Wired highlighted how nicotine and drugs derived from it promote the growth of new blood vessels and balance overactive immune systems. Nicotine is even being researched for a growing list of conditions, like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Of course, like so many substances, how nicotine affects the body depends on the dose and frequency. Chronic (long-term) use or high-frequency nicotine consumption carries the most risk.

Is Rapé Safe?

When working with rapé, side effects should be expected. The tribes call these reactions “cleaning.” This includes symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, sweating, vomiting, and diarrhea. Not everyone will experience these effects, but it’s best to be prepared.

From a Western perspective, tobacco snuff, or “smokeless tobacco,” does contain carcinogens [6]. Other common concerns regarding snuff products are the risk of heart disease, dental problems, and potential complications during pregnancy.

Most experts suggest rapé carries the potential for addiction as well. Traditionally rapé is used ceremonially, and like many indigenous perspectives on plant medicine, there’s wisdom in this approach. Ceremonial use prevents people from being able to abuse the plant and establishes a level of respect for the plant and how it should be used.

Perhaps one of the easiest ways to keep addiction in check is to use rapé with specific intentions and around some sort of ceremony. Casual use of rapé is not recommended.

How to Use Rapé (Hapé)

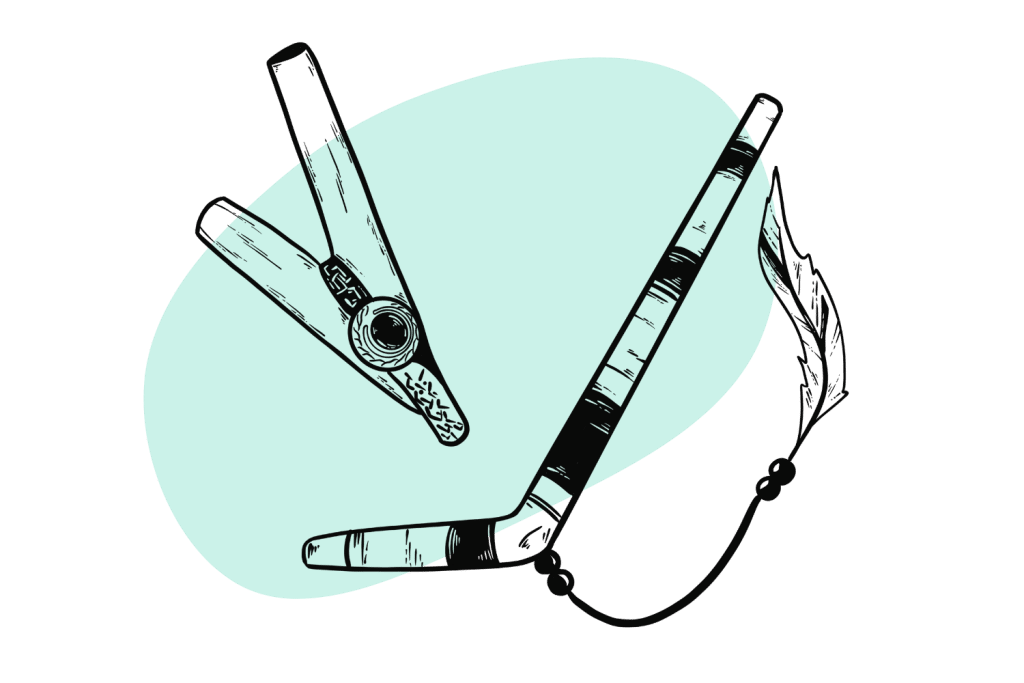

Rapé is traditionally used by blowing fine ground-up powder into the nostrils with specialty pipes. These pipes can be carved from bone or wood or be a piece of bamboo or reed.

There are two different types of rapé pipes:

- Kuripe — A rapé applicator shaped like a “V” for self-administering, also called “curipa.”

- Tepi — Commonly called a rapé pipe. A single long hollow tube is often made of bone, wood, reed, or bamboo for one person to “blow rapé” for another. Also called “tipi.”

What is a Rapé Ceremony?

While one can create a ceremonial container to use rapé within, the best introduction is with an experienced and trained facilitator. Tradition states that having someone blow you rapé means they are putting their life force into you, so choose someone you trust.

Rapé is often given outside for spiritual and practical reasons — such as a connection to nature — and you’ll be spitting, sneezing, and perhaps purging. Having a bathroom nearby is ideal in case of diarrhea, along with lots of tissue paper for blowing the nose.

The person giving or “blowing” rapé will sit across from the receiver. The blower will choose the appropriate amount based on the person’s experience level, the strength of the rapé, and intentions.

What To Expect: A “Typical” Rapé Ceremony Step-By-Step

- The rapé will be measured into the blower’s hand, and the rapé will say prayers, give blessings, or set intentions.

- If it’s your first time, the shaman will direct you. The usual instructions are to stay relaxed with your mouth slightly open.

- The pipe is inserted into one nostril while the blower exhales into the rapé pipe with their chosen breath (a nuance developed by trained rapé shamans).

- The receiver will feel a short burning sensation, and then the pipe will be inserted into the other nostril and rapé blown again.

- The receiver thanks the blower and finds a quiet spot to sit with the experience, which can last from a few minutes to hours in some cases. Effects can vary significantly, ranging from physical body sensations to insights to, in some cases, visions.

How to Give Yourself Rapé

Self-administering rapé is possible with a kuripe. This is best done in a quiet space where you will not be disturbed, ideally in nature and with a specific intention. Set and setting apply when using rapé. Having access to a bathroom and tissue paper is necessary in case of purges.

How to Self-Administer Rapé: Step-By-Step

- Measure out the amount of rapé you want. A pea-size dose for each nostril is a typically recommended starting point. Measure both doses into your hand.

- Put the first dose into the applicator. Insert the long end of the applicator into your nose and the short end into your mouth.

- Blow forcefully but not too hard. This exhale is not exclusively about force, although a strong blow is required. Tribes in the jungle have many different types of blows, each connected to different animals and with different effects. Experiment to find what works for you.

- Fill the applicator with the remaining rapé and do the other nostril.

- Close your eyes, relax, and breathe.

What’s in Rapé? (Rapé Active Ingredients)

Because there is no standard practice for how rapé is made, and its production is spread between many different tribes and now commercial producers, there is no standard formula.

Most rapé contains finely-ground tobacco along with some sort of tree ash and other locally-sourced medicinal plants.

Tobacco in Rapé

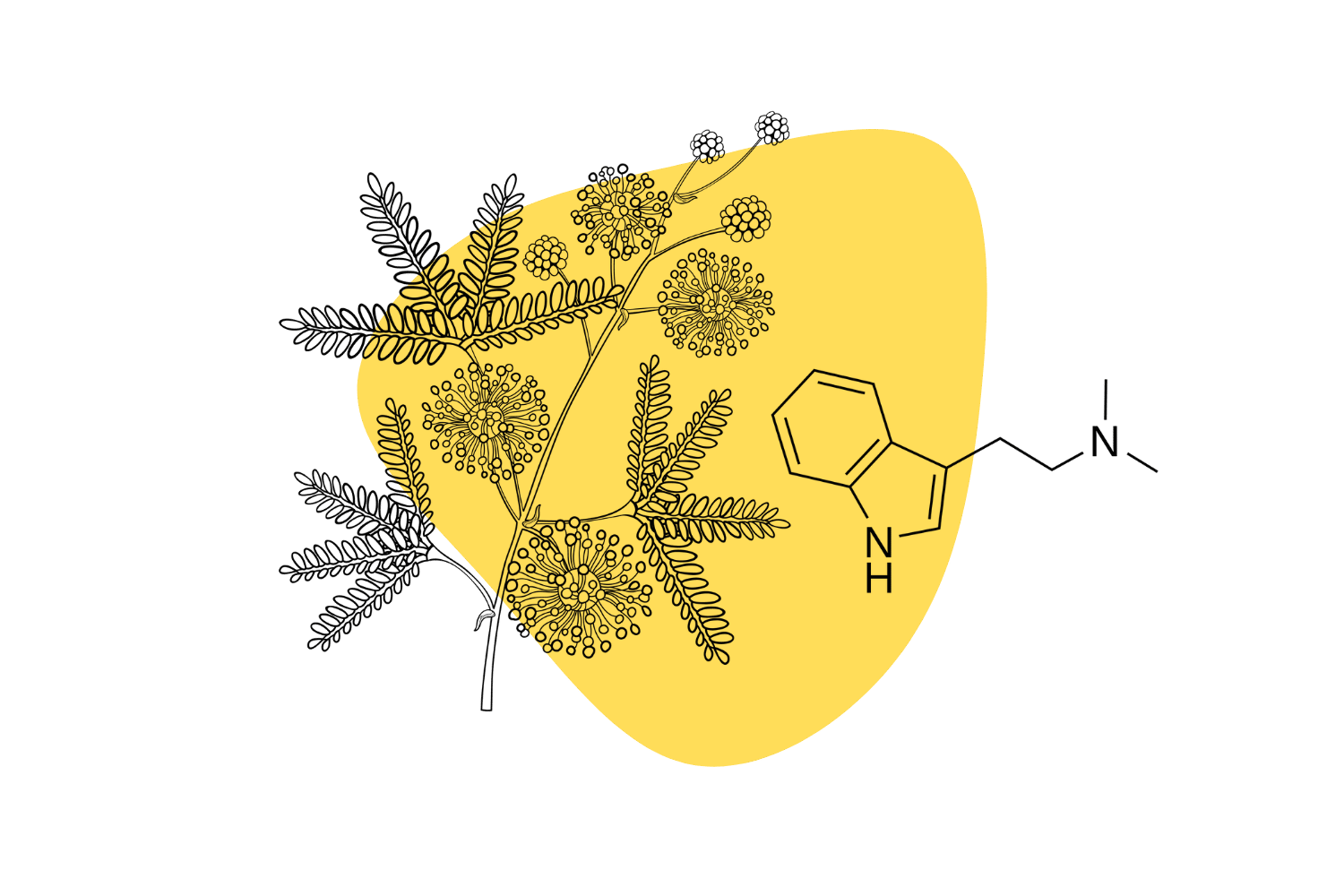

A typical rapé blend contains tobacco, ashes, and a wide variety of medicinal herbs and spices. However, not all rapé blends contain tobacco, and some can even contain psychedelic compounds like DMT (dimethyltryptamine).

Many rapés are made from a base of Tobacco rusticana, a tobacco plant native to South America. Other names include “mapacho,” “corda,” or “moi.” Rusticana notably has 20x the amount of nicotine of the common commercial Nicotiana tabacum.

Alkaline Ashes in Rapé

The other main ingredient is ash from hardwood trees, typically chosen for medicinal or spiritual significance.

While one would assume the active alkaloids in the plants are destroyed, in the book Shamanic Snuffs Or Entheogenic Errhines, Johnathan Ott explains that the perspective of the tribes is that the spirit of the plants is contained in the ashes. Working with ashes for therapeutic purposes is a practice found around the world in Ayurveda as Bhasma and modern alchemy practice known as spagyrics.

These are ritually prepared with both the wood and bark of the tree and make the tobacco more alkaline (raising the pH), which may help absorb active compounds, like nicotine, making the snuff more powerful.

Many different trees are used to reproduce ash for rapé. Typically the bark is used, as it is seen as having more medicinal properties, although sometimes the wood is included.

The trees used often go by local names, which vary between tribes and regions, so sorting out different species and Latin classifications is tricky.

Some examples include:

- Txunú, Tsunu, Sanu — Possibly Platycyamus regnellii, but the classification is contested. Some sources say it is Pau Pereira

- Pau Pereira — Geissospermum vellosii, or Geissospermum leave velloso

- Murici — Byrsonima crassifolia

- Cacao — Theobroma cacao, sometimes hulls are used too

Other Medicinal Plants in Rapé

The rest of the composition varies greatly. For medicinal effects, fragrance, and flavor, dozens of medicinal and aromatic plants can be included. These might be dried or added in their raw form, and some can be psychoactive, so read the label!

Some common examples include:

- Cinnamon — Miconia albicans

- Tonka bean — Dipteryx odorata, a common additive to smokeless tobacco products

- Mint — Mentha spp., quite a few varieties exist, creates a menthol-like effect

- Nutmeg — Myristica fragrans

- Yopo — Anadenanthera peregrina

How is Rapé Made?

Rapé production is traditionally a ceremonial process. Much of the rapé commercially available is still produced by tribes, although the knowledge of how rapé is made is spreading outside of the jungle, particularly in Brazil.

Traditionally the entire process was completed by a “Pajero” (a shaman) who followed a strict diet and sang specific songs and prayers throughout the process, putting intention in the mixture.

Making rapé is pretty labor-intensive, with only small amounts being produced at a time. The ceremonial aspects can only be learned from the tribes, which some keep secret.

The physical process of making rapé generally looks something like this:

- Wild tobacco is chopped and dried in the sun or over a low fire.

- The dry tobacco is beaten with special clubs or ground with mortar and pestle until it’s an extremely fine powder.

- Hardwood tree bark and medicinal herbs or spices are burned in a fire pit or sometimes placed into a pot over the fire. The plant material is reduced to fine white ash. This process is more art than science.

- The dry tobacco and ash are put through a fine sieve like a finely woven cloth until only the finest dust remains.

- The tobacco and ashes are mixed, typically at a ratio of 1:1.

- Other medicinal herbs, aromatic or flavourful plants, are blended with tobacco and ash.

How to Store Rapé

Rapé should be stored in a dark, cool, dry place. Sunlight can break down active compounds in many substances, and moisture can cause rapé to mold.

Traditionally rapé was kept in gourds or giant snail shells. Nowadays, keeping rapé in airtight containers is best. Glass or plastic with a tight-fitting lid is ideal, and opening the containers periodically may help avoid moldy flavors. Rapé with a rancid smell or taste should be discarded.

Exactly how long rapé will last in storage isn’t formally established and will depend on the production process and storage environment. Loss of potency over time should be expected, and studies of dry commercial tobacco snuff suggested the number of carcinogens (nitrosated alkaloids and NNK, possibly linked to cancer) increases with longer storage.

Takeaways: Rapé, Hapé, & Sacred Tobacco

Rapé is an ancient medicine that’s quickly spreading around the world as plant medicine rises in popularity. While this rise in popularity has brought some economic and cultural interest in traditional plant medicine practices of many Amazonian tribes, the use of rapé is quickly becoming a casual vice for many users.

While some tribes use rapé socially, its roots are as a medicinal preparation and spiritual connection to nature. Learning how indigenous cultures use plants is the foundation of modern psychedelic use. The spread of rapé represents an excellent opportunity to trigger greater curiosity and respect for tribes that still exist today and carry profound knowledge of plant medicine. However, the best way for rapé to assist with this is through intentional, responsible use.

References

- Kelton, M. C., Kahn, H. J., Conrath, C. L., & Newhouse, P. A. (2000). The effects of nicotine on Parkinson’s disease. Brain and Cognition, 43(1-3), 274–282.

- Ahmad Alhowail. (2021). Molecular insights into the benefits of nicotine on memory and cognition. Molecular Medicine Reports, 23(6), 1791-2997.

- Papke, R. L. (2014). Merging old and new perspectives on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemical pharmacology, 89(1), 1-11.

- Valentine, G., & Sofuoglu, M. (2018). Cognitive effects of nicotine: recent progress. Current neuropharmacology, 16(4), 403-414.

- Amir, S., Brown, Z. W., & Amit, Z. (1980). The role of endorphins in stress: Evidence and speculations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 4(1), 77-86.

- Wong, D. L., Tai, T. C., Wong-Faull, D. C., Claycomb, R., Meloni, E. G., Myers, K. M., … & Kvetnansky, R. (2012). Epinephrine: A short-and long-term regulator of stress and development of illness. Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 32(5), 737-748.

- Pavia, C. S., Pierre, A., & Nowakowski, J. (2000). Antimicrobial activity of nicotine against a spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens. Journal of medical microbiology, 49(7), 675-676.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (1991). IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: occupational exposures in insecticide application, and some pesticides (Vol. 53). Lyon, France: IARC.

- Roger A. Andersen, Harold R. Burton, Pierce D. Fleming, Thomas R. Hamilton-Kemp. (1989). Effect of Storage Conditions on Nitrosated, Acylated, and Oxidized Pyridine Alkaloid Derivatives in Smokeless Tobacco Products. Cancer Res, 49(21): 5895–5900.