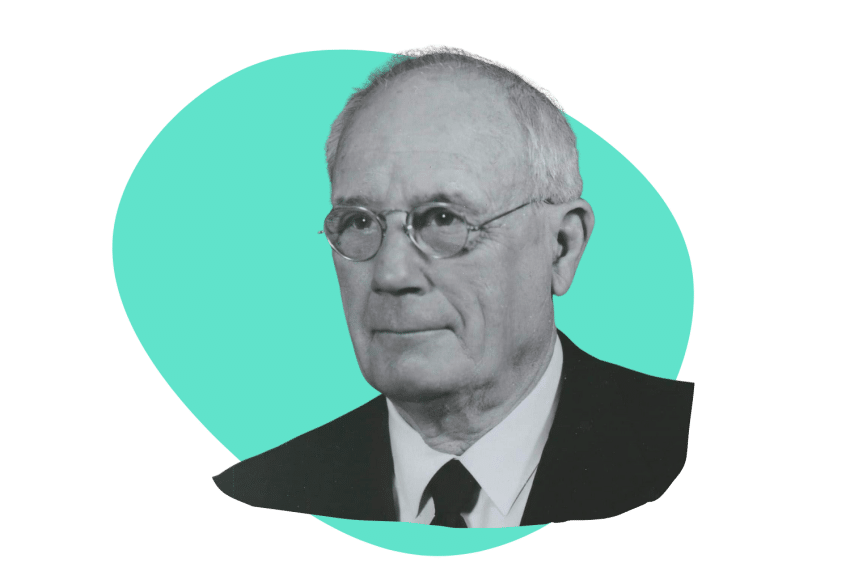

Richard Evan Schultes: “The Father of Ethnobotany”

Richard Evan Schultes paved the way for an era of psychedelic research and ethnobotanical study. He was a pioneer in his field and introduced the West to several sacred plants and medicines.

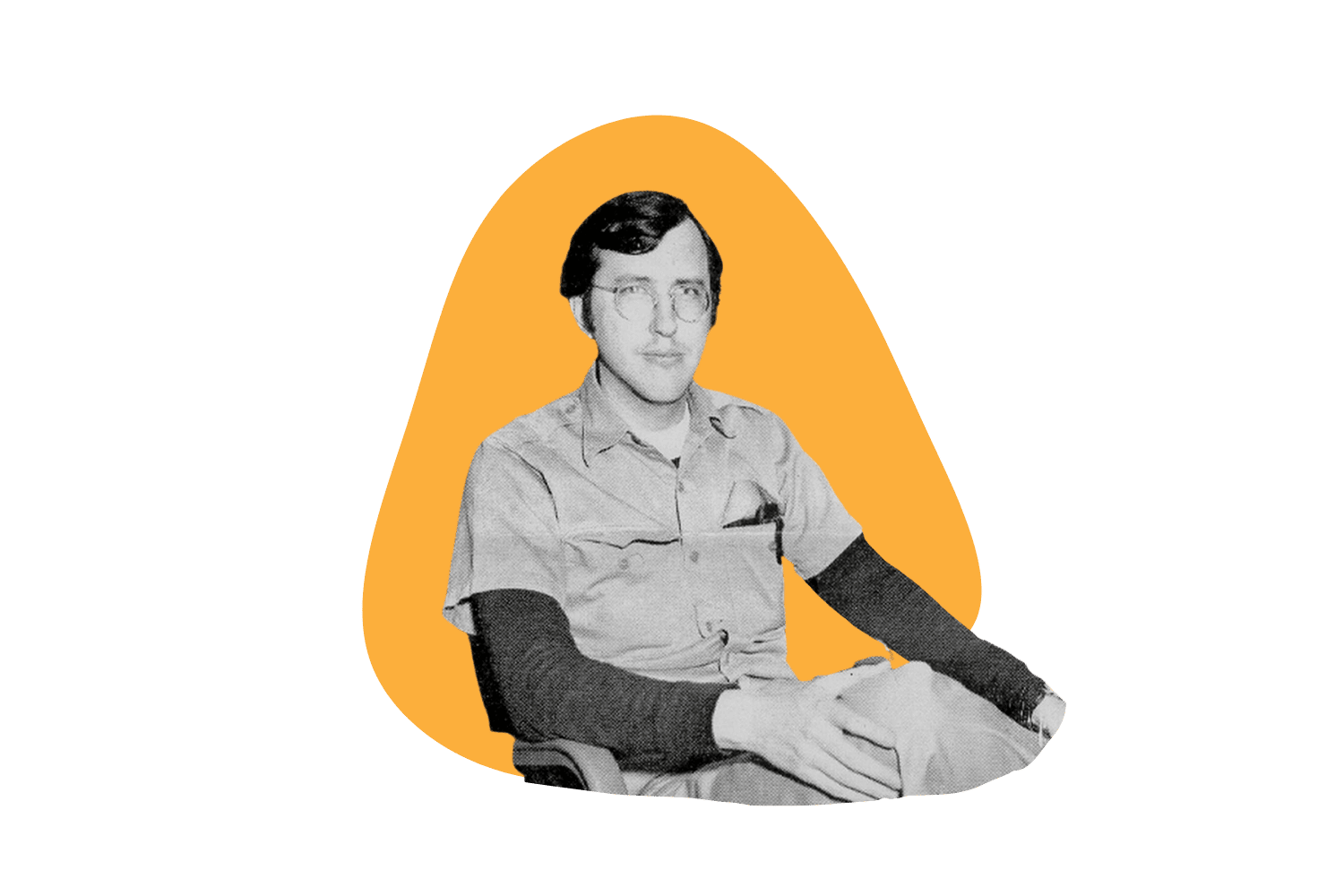

Richard Evan Schultes (1915–2001) was a pioneering scientist in the field of ethnobotany — the study of traditional knowledge concerning the medical, religious, and cultural uses of plants.

He started his life as a poor boy from Boston but ended up becoming the most famous, well-regarded, and most important explorer of the Amazon rainforest of the 20th century.

Schultes is an important figure in the world of psychedelics. He was the first Westerner to study ayahuasca in the Amazon, the first to discover the “sacred mushrooms” the Aztecs used and one of the people that helped discover psilocybin.

In this article, we’ll be delving into the fascinating life of R. Evan Schultes by looking at the following:

- Who is Richard Evan Schultes?

- What is he most famous for?

- Schultes’ early life and what inspired him

- His education and early expeditions

- Schultes’ life after he graduated from Harvard

- His groundbreaking research into the psychedelic brew ayahuasca

We’ve also compiled an extensive list of Schultes’ expedition notes, books, and research.

Who Is Richard Evan Schultes?

Richard Evan Shultes was an American ethnobotanist born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1915. He conducted extensive research on psychoactive and medicinal plants and their traditional uses by the indigenous peoples of South America.

Most of Shultes’ work centered around the Amazon rainforest and the tribes that reside there. He’s credited for discovering numerous plant species, including those used in traditional shamanic practices.

Through his research, Shultes made important contributions to the understanding of plant chemistry, the pharmacology of psychoactive plants, and the importance of traditional shamanic practices. He was the first Western scientist to study the psychedelic brew “ayahuasca.” His research into the brew helped introduce and popularize its use among Westerners.

Schultes worked for many years as a professor at Harvard University, and his research there significantly impacted the fields of pharmacology, anthropology, and ethnobotany. Several of his students from Harvard went on to become influential figures in these fields.

Over the course of his career, Richard Evan Schultes received numerous honors and awards, including the National Geographic Society’s Centennial Award (1988), the Gold Medal Award from the Linnean Society of London (1979), and the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement (1992).

Richard Evan Shultes passed away on April 10, 2001, at the age of 86. Today, he’s remembered as one of the most influential ethnobotanists of the 20th century — his work continues to inspire and inform researchers in the field of ethnobotany.

What’s Richard Evan Schultes Most Famous For?

Richard Evan Shultes is most famous for his pioneering work on the traditional uses of hallucinogenic plants, which he studied extensively in several parts of the Amazon rainforest (Colombia, Peru, and Brazil) and several regions in Mexico.

He’s known as the “Father of Ethnobotany,” and his research into ayahuasca and other traditional shamanistic psychedelic plant mixtures had a significant impact on the fields of anthropology, botany, and pharmacology.

Although he conducted numerous influential studies during his career, his research into ayahuasca is his most well-known and influential work. His work on the psychoactive plant mixture contributed significantly to our understanding of the pharmacology and chemistry of psychoactive plants.

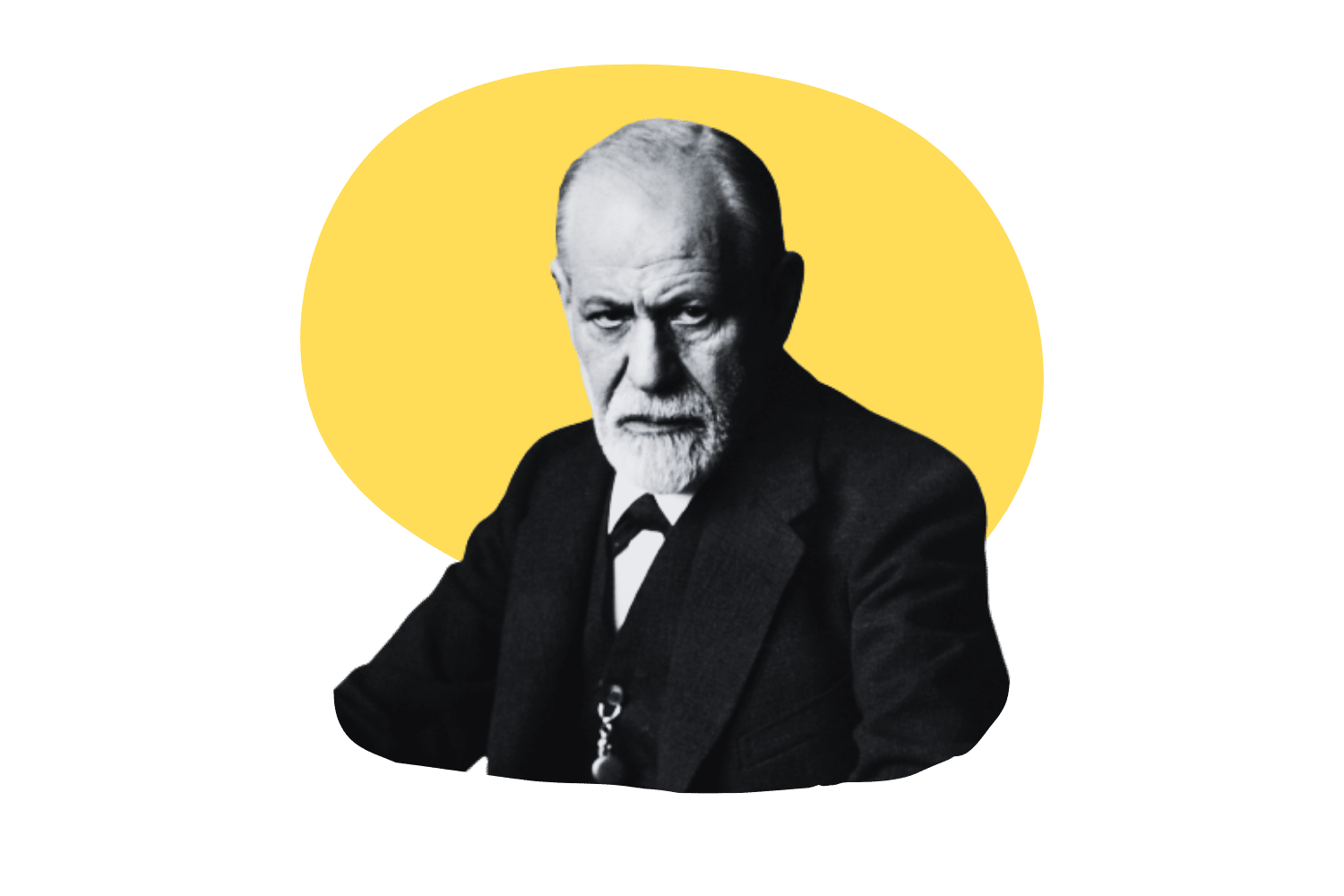

Schulte’s research on ayahuasca paved the way for other pioneering ethnobotanists, pharmacologists, and psychedelic researchers. His work influenced people such as Alexander Shulgin, Wade Davis, Mark Plotkin, Michael J. Balick, Terence McKenna, Dennis McKenna, and Rick Strassman.

Related: Top 10 Most Influential Women in Psychedelics

Richard Evan Schultes’ research on ayahuasca and other psychoactive and medicinal plants continues to be cited and built upon by scientists and researchers in the field of ethnobotany to this day.

The Early Life of Richard Evan Schultes

Richard Evan Schultes was born on January 12, 1915, in Boston, Massachusetts. He came from a working-class family of German and English immigrants — his father, Otto, was a plumber, and his mother, Maude, was a homemaker.

In his early life at home, Schultes had a severe stomach ailment that left him bedridden throughout the majority of his childhood. He’d spend much of his time lying in bed reading books that his father would bring him from the public library.

Schultes became fascinated with the tales of exploration, faraway lands, and indigenous cultures he read about. The book that would inspire him to pursue a life in ethnobotany was “Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and the Andes” — written by the 19th-century English botanist Richard Spruce [1].

Spruce became an idol to Schultes.

Spruce’s writing gave the young Richard Evan Schultes the drive to excel in his early education — hoping that one day he could follow in Richard Spruce’s footsteps and travel to meet the indigenous peoples of Amazonia.

Richard Evan Schultes’ Education & Early Expeditions

Richard Evan Schultes excelled during his school years and received a full scholarship at Harvard University for his efforts. He enrolled during the fall of 1933 at the age of 18, intending to study medicine. However, he had a change of heart when he took a job at the university, filing papers in the Harvard Botanical Museum for 35 cents per hour.

The extensive botanical collections at the museum gripped the young Richard Evan Schultes and inspired him to enroll in “Biology 104, Plants and Human Affairs.”

The class — taught by the renowned orchid expert and Harvard Museum director Oakes Ames — delved into a diverse array of subjects, from the history of wine and alcoholic drinks to the use of sacred plants and fungi.

This was Schultes’ first exposure to the world of ethnobotany — the study of traditional knowledge and customs of people concerning plants and their spiritual and medicinal uses.

Schulte’s First Paper — “Peyote: the Magic Cactus”

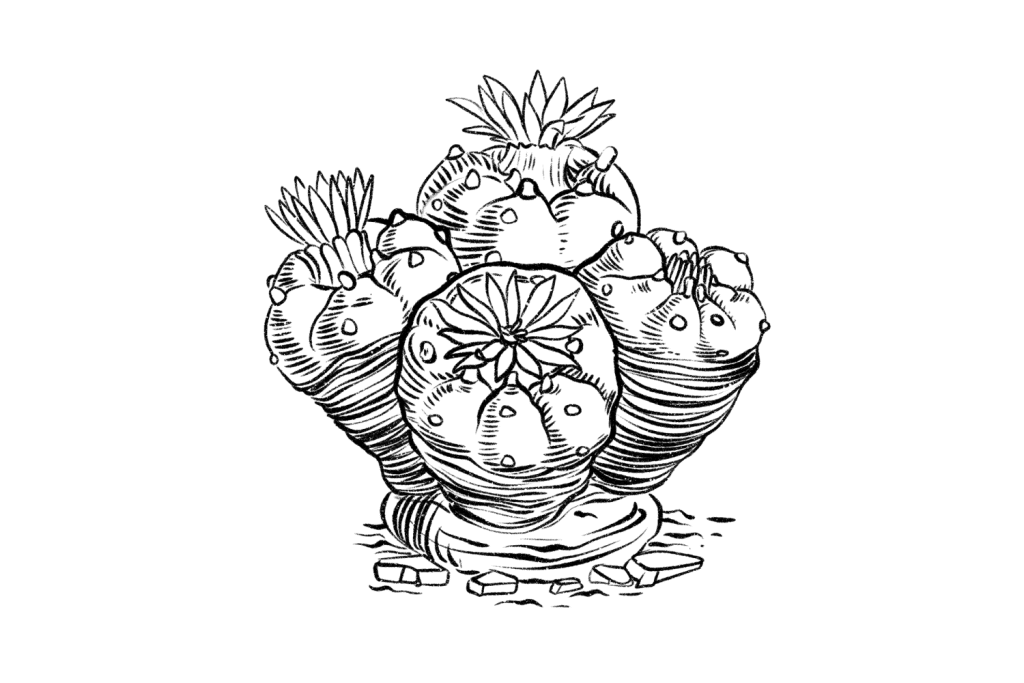

The students of the class were instructed to write a term paper based on one of the books from the classroom’s library of books. Schultes selected “Mescal: The Divine Plant and its Psychological Effects,” written by the German psychiatrist Heinrich Klüver, in 1928 [2].

The book described an early study of peyote — a psychedelic cactus native to Mexico and parts of Texas that induces powerful hallucinations from the active compound mescaline.

Schultes would travel to Oklahoma to study the peyote cactus and the Kiowa people — a Native American tribe that uses the cactus in their ceremonies. He shared the driving with anthropology graduate student Weston La Barre. With an unreliable 1928 Studebaker motorcar and a bit of determination, the pair arrived in the Kiowa community of Anadarko, Oklahoma, on June 24.

Schultes and La Barre had two main contacts for the expedition — Charlie Charcoal (a Kiowa leader) and his aunt Mary Buffalo (an elder with an extensive knowledge of the local flora). Thanks to Charlie and Mary, Schultes and La Barre visited 15 tribes throughout the summer and ingested peyote up to three times a week.

The pair partook in several peyote ceremonies, and Schultes describes these experiences in his 1937 paper “Peyote and Plants Used in the Peyote Ceremony” and his 1938 paper titled “The Appeal of Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) as a Medicine” [3, 4].

Although blown away by the visions he had during the peyote ceremonies, Schultes discovered that the cactus was far more than a visionary plant. A man from the Kickapoo tribe told Schutes that the Natives use peyote “as a white man uses aspirin.”

Many of the Native American tribes they encountered during the summer asserted the same view — claiming that when used correctly, peyote could cure a variety of ailments, and there’s little need for any other medicine.

“The Flesh of the Gods” — An Unexpected Discovery

While researching the peyote cactus, Schultes stumbled across an intoxicating substance used by the Aztecs known as teonanácatl — “Flesh of the Gods.” He was intrigued by these accounts and quickly learned that the substance was a psychedelic mushroom used for spiritual purposes.

Schultes found several pre-Colombian documents as well as Aztec artwork that outlined the significance of the mushroom.

One document, “Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus,” illustrates this sacred fungus with images of the seven gods holding mushrooms while beating a drum made from a human skull. It’s believed that the depiction describes the first encounter of teonanácatl by the gods.

Schultes read a thesis by William Safford — a leading botanist who worked for the United States Department of Agriculture — that discouraged the existence of these sacred mushrooms. Safford claimed that teonanácatl was peyote, and the Natives were trying to mislead the Catholic Church so they could consume the cactus without interruption.

Skeptical of Safford’s theory, Schultes went in search of the fungus. He didn’t understand how a cactus that grows in select regions of the northern deserts could be depicted by cultures that reside in the wet regions of southern Mexico.

Schultes came across a letter from Blas Pablo Reko — an Australian national living in Mexico — that was addressed to the Harvard Herbarium director J.N Rose. The letter stated that “the Flesh of the Gods” was indeed a psychedelic mushroom and was still used by the Mazatec tribes of Oaxaca.

In 1938, Richard Evan Schultes traveled to the mountainous region of Mexico to investigate the claims.

Schultes met with Blas Pablo Reko in Mexico City, and the two traveled by train to the Teotitlán region. The two quickly found evidence of mushroom use through divinators who offered advice through “mushroom ceremonies.” However, due to their sacred status, they struggled to find any samples of the mysterious fungus.

The two decided to venture into the mountains to more remote regions in search of the sacred shrooms.

After several weeks of climbing through the mountains, Schultes and Reko arrived in Huautla de Jiménez — the capital of Mazatec country.

While Schultes was laying plant samples he’d collected to dry, a Mazatec man approached him with a dozen small mushrooms. The man referred to them as “the Sacred Children” (niños santos) — were these the teonanácatl?

Schultes identified the mushrooms as a species of Panaeolus, but they were later correctly identified as a species in the Psilocybe genus — a family of mushroom species that contained the (not known then) psychedelic compound psilocybin.

Richard Evan Schultes had successfully discovered the sacred mushrooms that have been used for millennia. He had no context with the mushrooms, and the “mushroom ceremonies” they were used in still eluded him. However, he did find out that the mushrooms flourished in the region between June and September in boggy pastures.

Schultes would return to Oaxaca one year later to further pursue the mushroom and its uses.

Although unable to collect specimens due to the late onset of the rainy season that year, Schultes did manage to obtain five dried mushrooms in exchange for some quinine pills. Schultes consumed the mushrooms and described their effects:

“Shortly after ingestion of the mushrooms, the subject experiences a general feeling of levity and well-being. This exhilaration is followed within an hour by hilarity, incoherent talking, uncontrolled emotional outbursts, and, in the later stages of intoxication by fantastic visions in brilliant colors, similar to the visions so often reported for the narcotic peyote.”

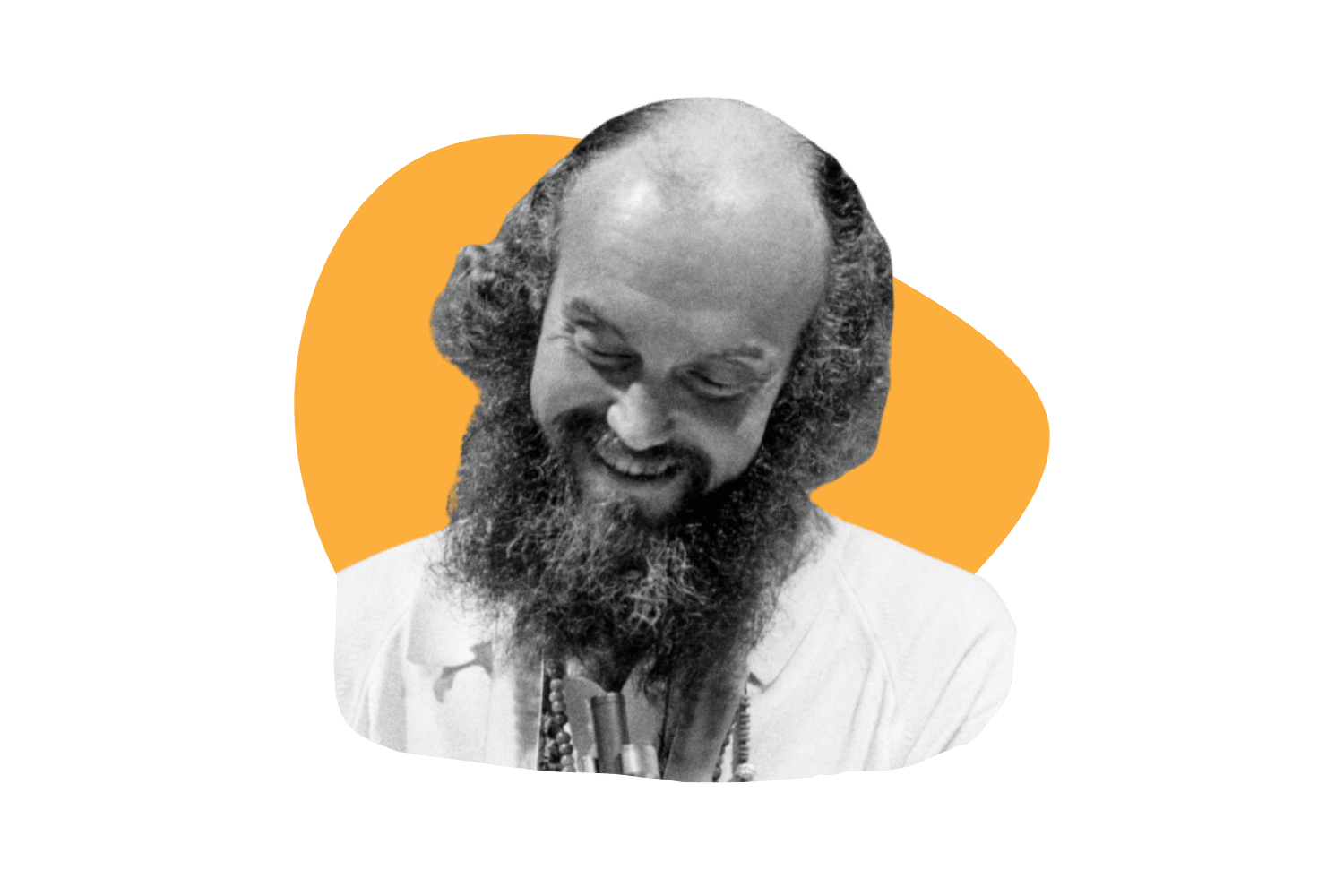

Schultes’ encounters with these sacred mushrooms would inspire another pioneering ethnobotanist by the name of Robert Gordon Wasson.

A renowned English poet called Robert Graves sent Schultes’ paper on teonanácatl to Wasson. He would then go on to launch several expeditions to the Oaxaca region, which eventually led to him meeting Maria Sabina and consuming the shrooms in one of her mushroom ceremonies in 1955.

Two years later, Wasson published an article in LIFE Magazine titled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” which quickly went viral [5]. This article introduced the West to magic mushrooms and paved the way for the psychedelic renaissance of the 1960s.

Schultes Discovers Coaxihuitl: “The Vine of the Serpent”

During his years of research into the peyote cactus and teonanácatl, Richard Evan Schultes discovered another sacred plant that was used by the Aztecs. This plant was known as Coaxihuitl — the Vine of the Serpent.

The plant Schultes was to encounter on his next expedition was Ipomoea corymbosa — a species in the family commonly known as “Morning Glory.”

The plant — with heart-shaped leaves and long white blooms — was said to have psychoactive seeds. When ingested, the seeds would cause intense hallucinations and “visionary” experiences.

Schultes searched far and wide for evidence of these psychedelic seeds. He spent several days collecting samples around San Juan Lalana before venturing south to Teotalcingo. He discovered reports of the locals of the area consuming psychoactive seeds from a vine that grew in the area, but he was unable to locate a specimen.

He continued south to the town of Santo Domingo Latani in the Choapam district. Here, he encountered a large vine bearing hundreds of fruits. The local curanderos didn’t hesitate to answer questions about the vine and the use of its seeds. Schultes found out that the plant — known as kwan-la-si among the Chinantec people — was a “medicine for divination.”

Schultes continued on his expedition and arrived at the Zapotec settlement of Yaveo. Here, he encountered more narcotic seeds, which the locals called kwan-do-a — “Children’s Medicine” in English.

Schultes and the Chinantec guides that accompanied him surveyed over 100 square kilometers of land across the Oaxacan highlands in search of the vine. His expedition helped solve the mystery surrounding “the Vine of the Serpent” and secured the botanical identity of the plant in question.

He also discovered exactly how the seeds of Ipomoea corymbosa were consumed in a ceremonial context. The natives of Teotalcingo and Santo Domingo Latani consumed around 13 seeds from the vine. They would mix the seeds with water, mescal, or tepache and drink the liquid at night in peaceful, silent surroundings.

In his 1941 paper titled “A Contribution to our Knowledge of Rivea Corymbosa,” Schultes outlined the effects produced by the sacred seeds [6]:

The intoxication begins shortly after the ingestion of ololiuqui. It rapidly proceeds to a stage where visual hallucinations appear. However, there is often an intervening stage of dizziness or giddiness followed by a feeling of general ease and well-being, lassitude, and increasing drowsiness.

Usually, the drowsiness develops into a stupor or a kind of somnambulistic narcosis. During this stupor, the patient is dimly aware of what is going on about him and is susceptible to suggestions. The visions which occur during the somnambulistic stage of the intoxication are described by the natives as very similar to those which are said to be induced by Lophophora williamsii and by Paneolus campanulatus var. sphinctrinus [sic].

They are often grotesque visions that portray people or thoughts, or happenings that have occupied the patient’s mind during the preceding hours. It is partly by means of these hallucinations and partly by means of the indistinct and delirious talking which accompanies the narcosis that the medicine man practices divination.”

Schultes’ Life After Graduation

Richard Evan Schultes left Harvard in 1941 with a Ph.D. He received a fellowship from the National Research Council to study the botanicals used in the creation of curare — a poison used to coat arrowheads used by hunters in the Amazon rainforest.

Schultes worked in the field throughout several different regions of the Amazon to discover the plants used to create poison. He discovered that curare derived from plants in the genera “Strychnos” and “Chondrodendron” — two tropical woody vines that produce the lethal toxins strychnine and Chondrodendron.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Schultes was called to put his botanical knowledge to patriotic use. Many of the British rubber plantations in Southeast Asia were under Japanese control — starving the Western market of rubber.

Rubber plants from the genus Havea are native to the Amazon rainforest and are a vital agricultural crop in the rubber industry. The wild rubber plants of the Amazon rainforest were a direct source of rubber before large-scale plantations were established in Asia. Once again, these wild plants became essential to the Western rubber market.

Richard Evan Schultes was employed by the Governmental Rubber Development Corporation in 1942 as a field agent in the Amazon rainforest. He began working on finding wild sources of rubber to meet the demand of the then-underserved market — his job was to locate Havea trees and teach the local people about the extraction and processing of rubber.

He collected hundreds of Havea seeds which would be used to develop breeding programs for high-yielding rubber plants during and after the war.

Schultes continued to work with rubber plants for the entirety of his career — traveling throughout South America and Asia. While in South America, Schultes traced the steps of his childhood idol — Richard Spruce. During his expeditions to follow in Spruce’s footsteps, he suffered repeated bouts of malaria, severe hunger, and several life-threatening situations.

While working in the Amazon for the Rubber Development Corporation, Schultes also undertook ethnobotany research under the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship.

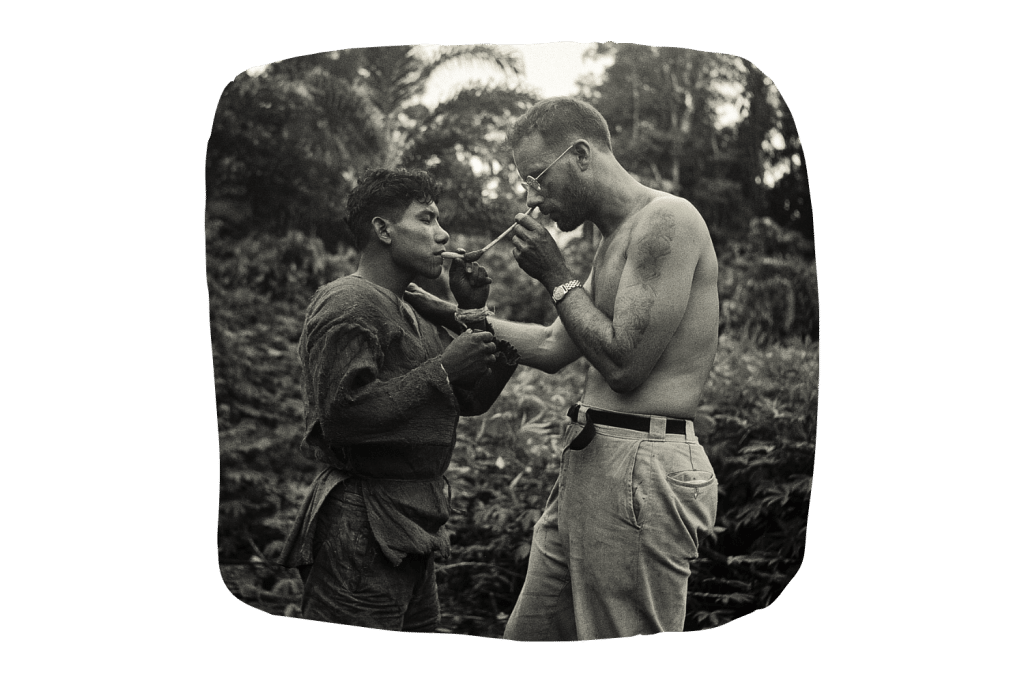

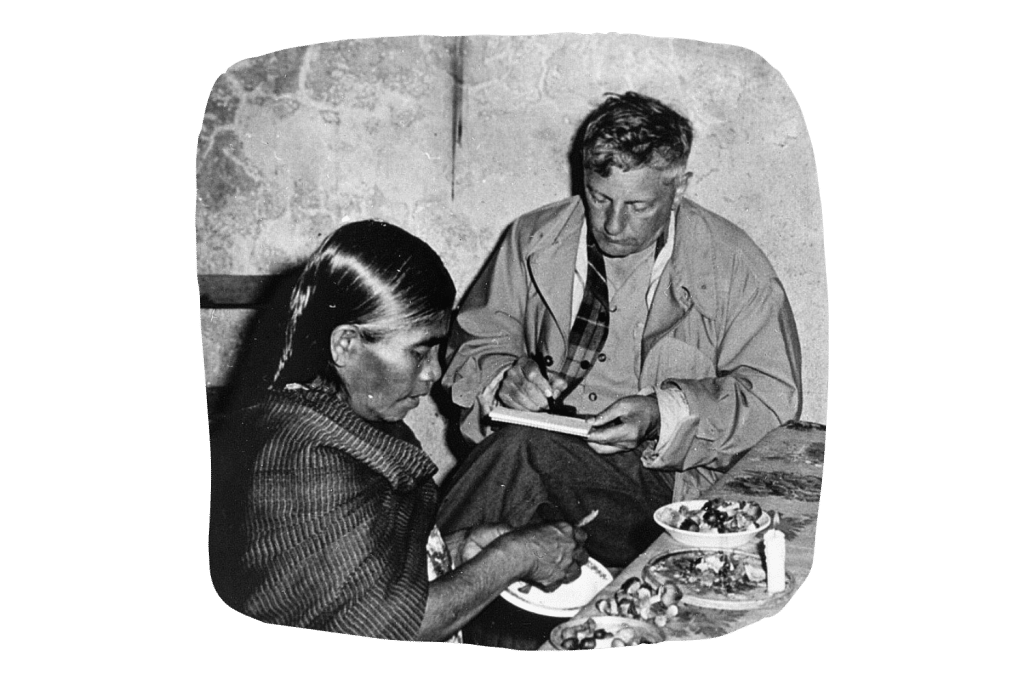

During his travels in the Amazon, he lived with the natives for extended periods — eating with the tribes, learning about their culture, and experimenting with the medicinal and hallucinogenic plants they consumed. Among the natives, Schultes was known as “the White Witchdoctor.”

It was during his work and expeditions of the Amazon that Richard Evan Schultes earned his reputation as the “Father of Ethnobotany” — this came from his research into the hallucinatory plant mixture ayahuasca.

Schultes’ Research on the Amazonian Brew Ayahuasca

Richard Evan Schultes explored the Amazon from 1941 to 1953 while employed by the Rubber Development Corporation — spending nearly 17 years in the rainforest. During his time in the Amazon, Schultes visited several ayahuasca-using indigenous tribes and participated in countless spiritual ceremonies involving the psychedelic brew.

Schultes’ documentation of ayahuasca and its use by indigenous Amazonian tribes was pioneering. His book Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers (1979) is an encyclopedia of the knowledge he gained throughout his time with these tribes.

The book contains information on several different aspects of ayahuasca, its use, history, cultural significance, preparation methods, pharmacology, chemistry, applications, and visionary effects.

The book contains a plethora of knowledge of the plant mixture and how it’s traditionally used as a visionary and spiritual tool. It features first-hand information and photographs that had never been seen by the Western world before.

Schultes was the first person to scientifically and taxonomically document the preparation and use of ayahuasca. He was also the first to botanically identify the plants used in the psychedelic brew. He identified the main active ingredients in ayahuasca as the vine “Banisteriopsis caapi” — known as “aya waska” in the Quechua language — and Psychotria viridis — a source of the psychedelic compound DMT.

“Aya Waska” translates to “vine of the soul” in English, and the original name shares the same pronunciation with the English-written name for the brew — ayahuasca.

Schultes spent much of his time in the Amazon with the Cofán people — indigenous tribespeople native to parts of the rainforest in the Sucumbíos Province of Northeast Ecuador and parts of Southern Colombia.

The Cofán shamans are renowned for their extensive knowledge of spiritual and medicinal plants from the rainforest. Schultes gained a plethora of knowledge from these natives. He learned their language, lived their lifestyle, took part in their daily activities, and helped in the preparation and ritualistic use of ayahuasca.

It was with the Cofán shamans that Schultes meticulously described the tribes’ use of psychedelic plant medicines and photographed never-before-seen images of ayahuasca preparation, use, and ceremonies. These images can be seen in his 1992 book “Vine of the Soul: Medicine Men, Their Plants and Rituals in the Colombian Amazon.”

The book focuses solely on ayahuasca and its use by the Cofán and other indigenous tribes of the Amazon.

Although Schultes identified the main active plant in the brew as the Banisteriopsis caapi vine, he noted several other plants that were used in ayahuasca throughout different regions. He reported that Diplopterys caberana and Psychotria viridis were employed in the brew by tribes over a wide area of the Amazon.

Schultes discovered that when the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and Diplopterys caberana or Psychotria viridis were combined, the brew would induce strong psychedelic effects that would often last several hours. However, when used solely, no effects were noticed.

We know now that this is because DMT (the active ingredient in ayahuasca) isn’t orally active. When plants with high levels of DMT are mixed with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), the compound becomes orally active and can be absorbed by the human body. The Banisteriopsis caapi vine contains various harmala alkaloids — an MAOI.

The shamans of the Cofán were so knowledgeable about the local flora that they knew exactly which plants to mix to make the DMT active — even if they didn’t know exactly how the mixture worked on a chemical level.

Schultes noted that the shamans were so adept that they could distinguish between different ayahuasca vines that looked identical to the untrained eye but produced differences in effects when brewed. The shamans told Schultes that much of this plant knowledge was given to them during ayahuasca experiences — providing them with knowledge through “supernatural” means.

Schultes partook in several ayahuasca ceremonies throughout his time in Amazon and became a “white” legend among the native people of several Amazonian regions. He discovered that many tribes of the Amazon treated ayahuasca ceremonies as a right of passage for people coming of age or newcomers to the tribe.

Almost every new tribe Schultes met would “initiate” him through an ayahuasca ceremony to help him integrate into their way of life.

Schultes can be credited for making ayahuasca popular among the Western world and is one of the pioneering bodies that introduced the psychedelic brew to the West.

Although Schultes brought ayahuasca to the attention of the Western world, the ceremonies he partook in were worlds apart from the ayahuasca ceremonies people from overseas partake in today. The boom in “psychedelic tourism” has led to Amazonian facilitators altering the ceremonies to fit the desires of Western “Psychotourists.”

Richard Evan Schultes’ Botanical Discoveries

Richard Evan Schultes made thousands of botanical discoveries. Over the course of his time in the Amazon, he identified a total of 24,000 plants (around 300 of which were unknown to science) and over 2,000 medicinal plants that were used by Amazonian natives.

Some of Schultes’ most notable botanical discoveries include:

- Psychotria viridis — Schultes discovered and identified this Amazonian plant as the primary source of DMT — the hallucinogenic compound present in the ayahuasca brew that’s used in traditional Amazonian shamanic practices.

- Tabernanthe iboga — Schultes identified this African plant as the source of ibogaine — a psychoactive alkaloid used in traditional spiritual, medicinal, and healing rituals by several tribes across Africa.

- Banisteriopsis caapi — Schultes identified this Amazonian vine as a key ingredient in ayahuasca that makes DMT orally active. This vine was a constant in all the ayahuasca brews Schultes came across in the Amazon.

- Theobroma grandiflorum — Schultes discovered and described this Amazonian plant (also known as Cupuaçu). It’s widely used by tribes in the Amazon rainforest for its edible fruits and potential medicinal properties.

- Paullinia yoco — Schultes identified this Amazonian plant as the source of “yoco” — a stimulant-type brew with light hallucinogenic qualities that are traditionally used by indigenous peoples (especially hunters) in the Amazon rainforest.

- Virola — Schultes identified and described numerous species within the genus “Virola” — tree species that are used by indigenous peoples in the Amazon for their psychoactive and medicinal properties.

- Myristica fragrans — Also known commonly as “nutmeg,” Schultes conducted research on this plant and identified its psychoactive properties.

- Erythroxylum coca — The primary source of the stimulant drug cocaine — Schultes studied its traditional use by indigenous peoples in the Andean region as a stimulant and acclimatization medicine.

- Ayapana triplinervis — Schultes discovered and described this Amazonian plant, which is used for medicinal purposes by indigenous communities in the Amazon rainforest. It’s commonly used to heal wounds and control blood coagulation.

- Thevetia peruviana — Schultes studied this Mexican plant and identified its potential use as a treatment for cardiac arrhythmia.

Richard Evan Schultes’ Contributions

Richard Evan Schultes made several contributions to the fields of botany, ethnobotany, pharmacology, and biology. He has also made significant contributions to conservation, the environment, and the preservation of indigenous cultures.

He was the first person to inform the globe about the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, the decline in rare species and their habitats, the disappearance of its native people, and cultural assimilation through Western involvement.

Schultes strongly advocated for the conservation of rainforests and the preservation of their indigenous cultures. He warned the public about the destruction of traditional knowledge and cultural diversity that comes with the loss of indigenous communities and their relationship with the natural world.

He believed that preserving the traditional knowledge of indigenous communities was critical. He helped preserve this knowledge by documenting and promoting the traditional uses of medicinal and healing rainforest plants to help establish “community-based conservation initiatives.”

He warned about the loss of biodiversity and ecological services in the Amazon that comes with the destruction of rainforests through timber extraction and farming. He called for urgent action to protect the rainforest environment and advocated for rainforest conservation as early as the 1960s.

His work helped to bring the environmental issues associated with the Amazon rainforest to the public consciousness. Although no immediate action was taken when Schultes warned the Western world about the devastation, he inspired subsequent generations of researchers and conservationists to continue his legacy and fight for conservation.

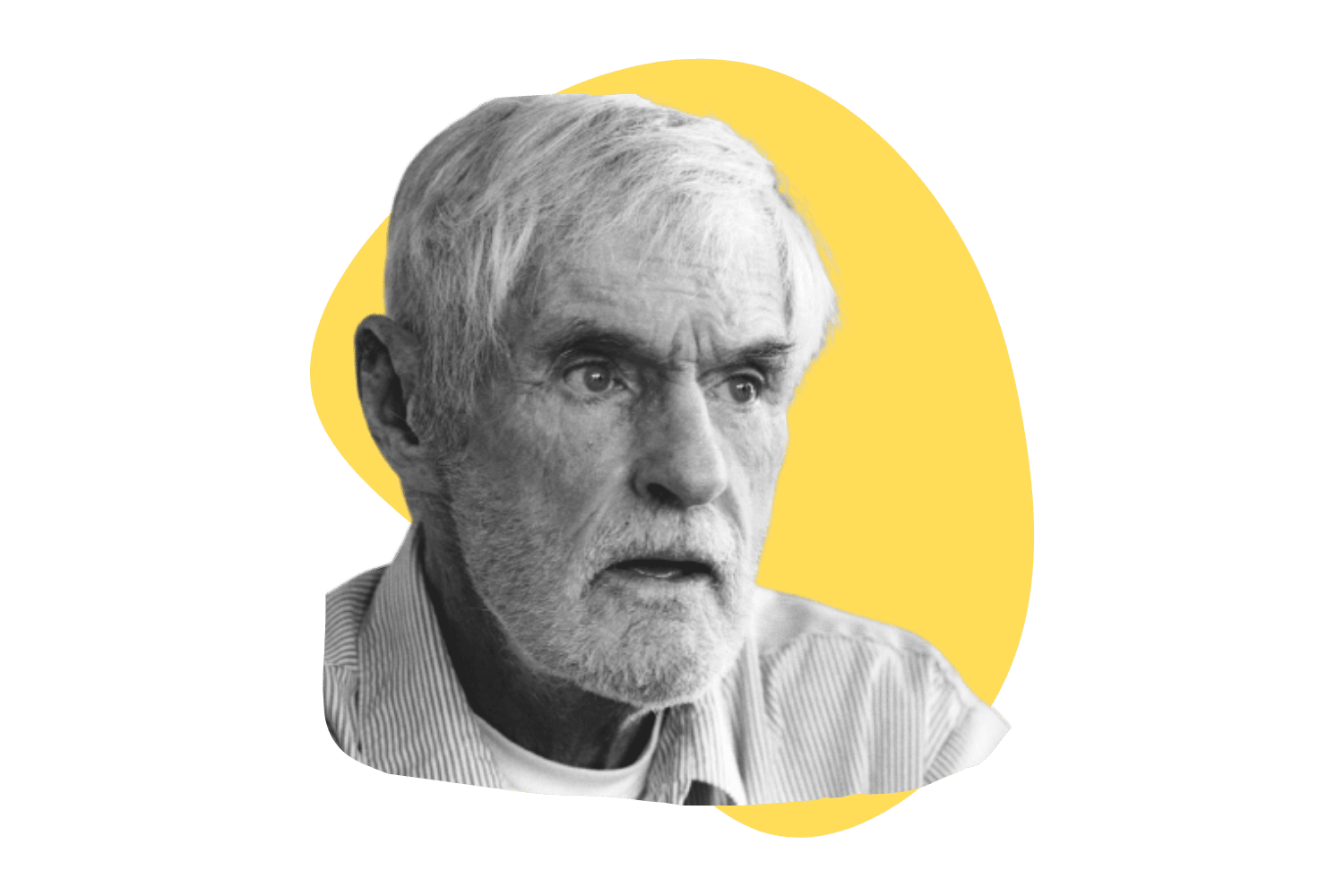

Schultes trained and inspired hundreds of young researchers and students in ethnobotany during his years at Harvard University. He personally trained the renowned Canadian anthropologist and ethnobotanist Wade Davis who went on to become an influential writer and “Explorer-in-Residence” at the National Geographic Society.

Schultes’ work has had significant implications for the fields of ethnobotany, pharmacology, and conservation biology. Throughout his career, he was honored and awarded for his efforts…

Richard Evan Schultes’ Awards & Honors

Richard Evan Schultes received many awards and honors throughout his long and distinguished career as an ethnobotanist.

Here are some of Schultes’ most notable awards:

- Gold Medal Award from the Linnean Society of London (1979)

- Distinguished Economic Botanist Award from the Society for Economic Botany (1980)

- David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration from the National Tropical Botanical Garden (1982)

- Order of the Southern Cross from the government of Brazil (1987)

- Gold Medal Award from the New York Botanical Garden (1987)

- International Cosmos Prize from the Expo ’90 Foundation (1990)

- National Geographic Society Centennial Award (1988)

- Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement (1992)

These awards recognized Richard Evan Schultes’ groundbreaking discoveries and his contributions to the field of ethnobotany, his role in advancing the understanding of traditional plant medicines, and his efforts to promote environmental conservation and sustainability.

Schultes’ Best Quotes

Adventures happen only to those incapable of planning an expedition.”

One wonders how people in primitive societies, with no knowledge of chemistry or physiology, ever hit upon a solution to the activation of an alkaloid by a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Pure experimentation? Perhaps not.”

The Indians’ botanical knowledge is disappearing even faster than the plants themselves.”

You have a feeling of achievement when you discover a new plant, even a plant that has no use.”

I have tried several of the Indian hallucinogens, in part because the Indians consider them sacred plants and it would have been an unpardonable rudeness to refuse them when the Indians were kind enough to offer them to me during a ceremony.”

It is therefore our responsibility — nay, our duty — to put ourselves in the forefront of ethnobotanical conservation. We cannot allow such precious funds of knowledge to become extinct.”

What should concern us, is the advisability of intensive chemical and pharmacological investigations of the cactus family, especially the genera related to peyote. There has never been a concerted screening of this family for potential medicinal properties.”

Books By Richard Evan Schultes

Richard Evan Schultes wrote and contributed to several titles in botany, ethnobotany, and mycology. He also released several scientific papers on plant medicines, natural psychedelics, cultural and spiritual practices, environmental conservation, and toxic plants and fungi.

Schultes’ most famous book is “Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers” but he has published, co-authored, and contributed to many others. A selection of his field notebooks was gathered and published as books in 2021 as well — these provide a fascinating insight into the travels of Richard Evan Schultes and his ethnobotanical research.

Here are the titles that Richard Evan Shultes has written, co-authored, or featured in:

- Native Orchids of Trinidad and Tobago: International Series of Monographs on Pure and Applied Biology — Published in 1960

- The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens — Published in 1973

- A Golden Guide: Hallucinogenic Plants — Published in 1976

- Teonanácatl: Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of North America — Published in 1978

- Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers — Published in 1979

- The Glass Flowers at Harvard — Published in 1982

- Where the Gods Reign: Plants and Peoples of the Colombian Amazon — Published in 1988

- The Healing Forest: Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia — Published in 1990

- Vine of the Soul: Medicine Men, Their Plants, and Rituals in the Colombian Amazonia — Published in 1992

- Ethnobotany: Evolution of a Discipline — Published in 1995

- The Journals of Hipolito Ruiz — Published in 1998 (Translation by R. Evan Schultes)

- The Lost Amazon: The Pioneering Expeditions of Richard Evans Schultes — Published in 2004

- Field Notebook: Oaxaca, Mexico, 1938 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Igara Paraná River, Colombia, 1942 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Rio Madeira, Brazil, 1945 — Published 2021

- Field Notebook: Rio Amazonas and Sergipe, Brazil, 1946 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Norte De Santander, Colombia, 1941 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Peru and Colombia, 1945 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia and Brazil 1945 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1940 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1941 — Published in 2022

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1942 – 1943 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1945 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1952 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Colombia 1960 – 1970 — Published in 2021

- Field Notebook: Mexico 1938 — Published in 2021

Richard Evan Schultes’ Expedition Notes

Throughout his expeditions across the globe, Richard Evan Schultes documented his experiences and findings in note form. Several of his notebooks were published as hard copies in 2021, but many more are available online.

Alongside his expedition notes, Schultes also listed the plants discovered during his expeditions. These “plant lists” include the common names of the plants he collected as well as some of their traditional, medicinal, and cultural uses.

Below is an archive with links to the digitized versions of Richard Evan Schultes’ notebooks and plant lists:

- Notebook 1, 1952 August-November. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 9. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 2, 1940. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 1. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 3, 1952 April-June. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 8. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 4, approximately 1945-1947. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 5. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 5, 1952 February. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 6. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 6, approximately 1967. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 10. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 7, 1982. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 13. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 8, approximately 1975. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 12. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 9, 1971 April. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 11. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 10, 1944-1983 (bulk 1944). Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 3. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 11, 1944. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 4. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 12, 1943-1944. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 2. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Notebook 13, 1952 February-March. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 7. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Oaxaca plant list, #s 490-675, 1938. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 14. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Oaxaca and Guerrero plant list, #s 1-63, 510-757, R50-R65, 1938. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 15. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 12043-12551, 1941. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 16. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Norte de Santander plant list, 1941. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 17. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 3200-3698, 1-56, 1942. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 18. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 3700-3753, 3981-4011, 4030-4093, 1942. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 19. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Igara Parana plant list, #s 3770-4003, 1942. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 5100-5330, 1942-1943. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 21. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 5350-5607, 7000-7277, 1943. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 22. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 5608-5720, 7278-8046, 1943-1946. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 23. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 5850-5888, 1944. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 24. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 6300-6397, 1945 April-May. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 25. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Peru plant list, #s 6400-6421, 1945 April-May. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 26. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Rio Madeira plant list, #s 6490-6534, 1945 July-August. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 27. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- South America plant list, #s 6535-6820, 1945 September-November. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 28. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- South America plant list, #s 6821-6969, 8104-8569, 1946. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 29. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Brazil plant list, #s 8713-9148, 1947 September-November. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 30. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Brazil plant list, #s 9160-9738, 1947 November-December. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 31. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- South America plant list, #s 9739-10269, 1948 March-July (bulk), 1950. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 32. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Brazil plant list, #s 10270-10384, 1947-1948. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 33. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 16785-16872, 1952. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 34. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 19215-20235, 1953. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 35. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 22400-22494, 1960 July. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 36. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 22500-22720, 1960 July-August. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 37. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 24000-24413, 1966. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 38. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Rio Negro plant list, #s 24500-24630, 1967. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 39. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 2311-2391, 1969. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 40. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 26000-26101, 1970. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 41. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Manaus plant list, #s 26100-26205, 1972. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 42. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

- Colombia plant list, #s 26300-26364, 1972. Richard Evans Schultes papers, ecb00004, Series VI, Box: 3, Folder: 43. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

References

- Spruce, R., & Wallace, A. R. (1908). Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes…: In 2 Vol…. Clark.

- Klüver, H. (1928). Mescal: the divine plant and its psychological effects.

- Schultes, R. E. (1937). Peyote and plants used in the peyote ceremony. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 4(8), 129-152.

- Schultes, R. E. (1938). The appeal of peyote (Lophophora williamsii) as a medicine. American Anthropologist, 40(4), 698-715.

- Wasson, R. G. (1957). Seeking the magic mushroom. Life, 42(19), 100-120.

- Schultes, R. E. (1941). Contribution to our knowledge of Rivea corymbosa.