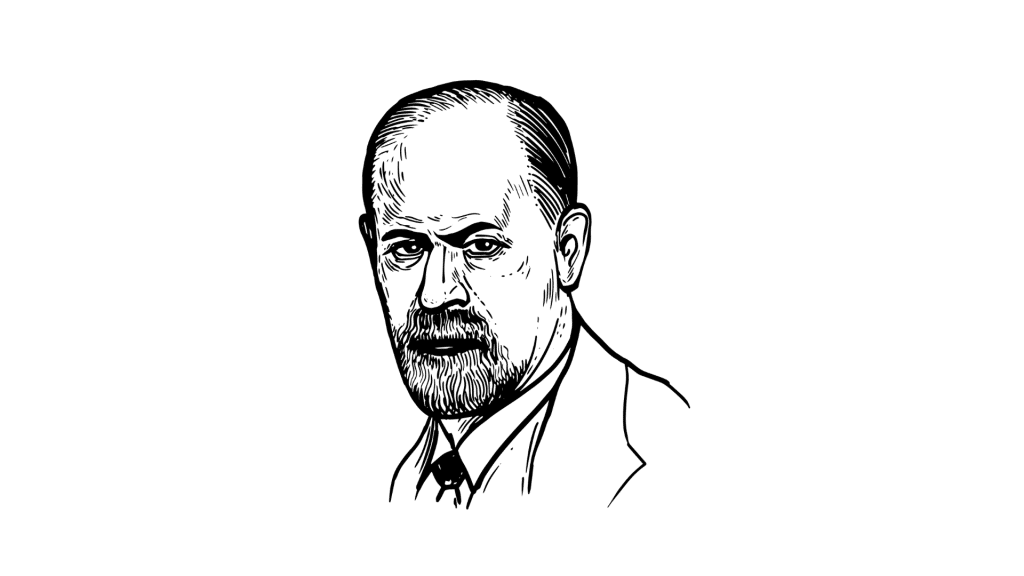

Sigmund Freud: Consciousness, Ego, & Defense Mechanisms

Meet the father of psychoanalysis.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist known as the father of psychoanalysis.

Although his work has been heavily criticized, he was a revolutionary at his time, and much of his theory still lives at the base of modern psychology and psychotherapy.

Within his psychoanalytic model, he developed several structures and theories that sought to explain the psyche’s structure, development, and influence in social relationships.

Some of the most notorious work in his study of the psyche includes:

- The structure of the psyche: This includes the realms of the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, as well as the ego, id, and superego.

- The theory of the ego’s defense mechanisms: A set of unconscious defenses that the ego enacts when threatened.

- His psychosexual development theory: A human development theory that seeks to explain the development of sexual drive, which Freud believed to be a primary player in human behavior.

- Psychoanalytic therapy: His model of exploring the psyche of patients and healing its ailments.

In his article, we will take a look into Freud’s life and work and explore the major concepts of his psychoanalytic theory.

The life of Sigmund Freud

Freud was born to Jewish parents in 1856 in what we now know as Příbor, Czech Republic.

Early in his infancy, his family moved to Vienna, where he spent most of his life.

After graduating from school at the age of 17, Freud began his medical studies at the University of Vienna. There he worked with physician Ernst von Brücke, a well-recognized physiologist of his time.

In 1882 he joined the Vienna General Hospital and trained with Hermann Nothnagel, professor of internal medicine and psychiatrist Theodor Meynert.

Freud eventually left Vienna in 1934 with his wife and daughter after Austria was annexed to the Nazi Germany regime. By this time, most of his notorious work was done, and he lived the last part of his life in London.

His work is believed to be greatly influenced by his experience living in close proximity to Germany’s anti-semitic and imperialist authority of the time.

Hysteria & Freudian Therapeutics

Several years after his work in the Vienna General Hospital and a few blows to his reputation in the medical field — namely his unsuccessful studies on the pharmaceutical benefits of cocaine — Freud moved to Paris to continue his studies in neuropathology.

There he joined the Salpêtrière neurological clinic, where he worked with Jean-Martin Charcot observing patients with so-called “hysteria.”

Hysteria was then used as an umbrella term for a realm of seemingly unexplainable and uncontrollable somatic and psychological symptoms.

The word “hysteria” comes from the greek “hystera,” which means “uterus,” so hysteria was a common yet grossly misinformed diagnosis for women with severe psychosomatic symptoms at the time. Now we know that such symptoms are common in women victims of incest, rape, torture, and other severely traumatizing experiences.

Freud’s work with this population influenced his career in three main ways:

1. It Provided a Base for His Theory of Sexual Development & Fixation

His common encounters with sexual content while working with this population strengthened Freud’s view of sexuality and sexual urges as a root of human behavior and a big part of the unconscious mind.

2. It Introduced the Difference Between Brain & Mind

Freud started to hypothesize with this work that the symptoms and behaviors of his patients were not a problem with their brain but a product of their mind.

With this new separation of brain and mind, Freud began his exploration of the human mind and his study of the unconscious.

3. It Created the Framework for Psychoanalysis as a Practice

Working with patients at the clinic, Freud started to implement some of the methods that became the root of his therapeutic practice, including free association, his version of what we would now know as talk therapy, dream analysis, and even hypnosis.

The Architecture of the Mind: Conscious, Preconscious, & Unconscious

As Freud dabbled into the separation between the mind and the brain, his studies around the mind or psyche led to his proposal of the architecture of the psyche.

This model is now famous in psychoanalysis theory and has been used to analyze human behavior not only in a therapeutic field but in culture, politics, literature, and philosophy as well.

Freud’s model of the unconscious has been explored in famous pieces of literature like Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Albert Camu’s The Stranger, and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye to name a few.

In this theory of the mind’s architecture, Freud introduced the concepts of the three layers of consciousness: The conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious, and the three main players within these layers: Ego, id, and superego.

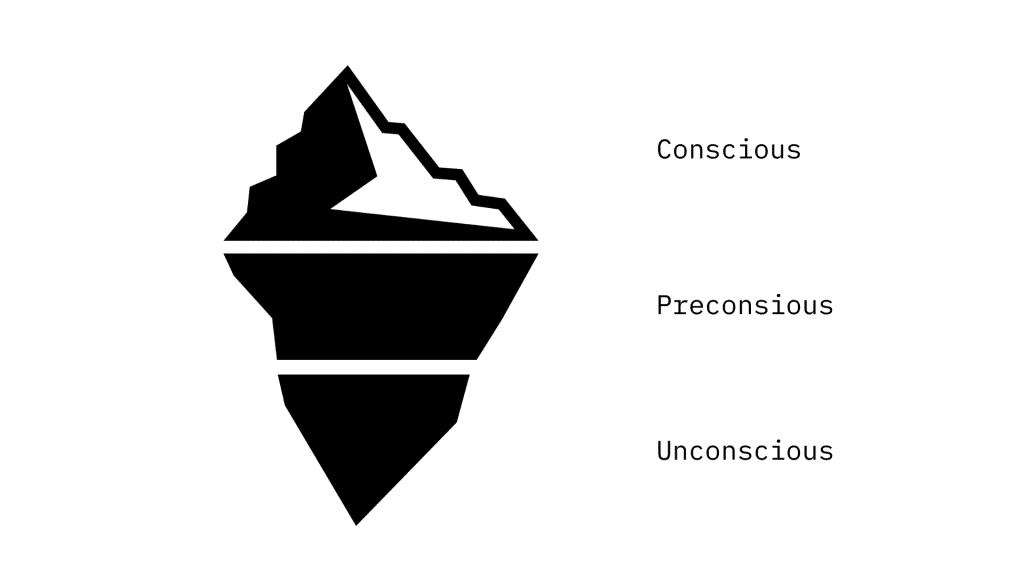

“The mind is like an iceberg, it floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.” — Freud

Most people are now familiar with Freud’s metaphor of the iceberg to describe the architecture of the mind. He states that conscious awareness is just the small tip of the iceberg and that underneath lies most of the mind submerged in the unconscious.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the elements of the psyche.

1. The Conscious Mind

The conscious mind, as its name states, refers to the parts of our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that we are aware of and conscious of.

Freud proposed that the conscious mind is just the tip of the iceberg, so there is far more material that we are not consciously aware of in our minds.

2. The Preconscious Mind

The preconscious mind is Freud’s model of the psyche refers to a part between conscious and unconscious. This is a part of our inner life that we can access if we try and can be seen with some work, but it is not readily accessible like the contents of the conscious mind. Our accessible memories and learned experience live in the preconscious.

In the iceberg metaphor, this is the part that’s under the water’s surface and can still be seen with some effort but is not clear as the part above water.

3. The Unconscious Mind

The unconscious mind is the part of the psyche that is completely removed from any conscious awareness. In Freud’s model, it’s also by far the largest part of the mind. Freud believed that the unconscious governed and informed every other part of the psyche.

In the iceberg analogy, the unconscious is the majority of the submerged iceberg, the part that extends so far underwater that it is impossible to see from above.

The unconscious was a large area of fascination for Freud as well as many of his predecessors like Carl Jung, whose work also revolved around the unconscious mind and eventually parted from Freud’s view when he introduced the collective unconscious.

Within the levels of consciousness, the ego, id, and superego all play a role:

A) Ego

The ego lives somewhere between the conscious and preconscious. It’s the portion of the mind that experiences life, our sense of self, and identity.

B) Id

The id lives entirely in the unconscious. It is the instinctive, uncontrollable portion of the mind. The part that holds all impulses suppressed thoughts and urges.

C) Superego

The superego expands all the way from the depths of the unconscious to the tip of the conscious mind. It’s the reigning force that controls the impulsive, reckless nature of the id and acts through the ego. It is our sense of morality, and it harnesses the power that allows us to behave in a civilized society.

Ego & Id: The Rider & The Horse

A good way to understand the dynamics of ego, id, and superego is the analogy that Freud himself introduced of the horse and the rider.

The horse in this metaphor is the embodiment of the id — the instinctive, impulsive, and animalistic part of the consciousness full of carnal desire. This is the part of the unconscious that knows what it wants and as if unrestrained will do what it needs to get it.

This includes every impulse and drive from basic, instinctive needs like food, rest, and reproduction, to the most socially shunned, dark, and destructive urges and fantasies that may lay repressed in the unconscious.

The rider represents the ego. She guides the powerful force of the id (the horse) and harnesses its strength to take the path she wants.

The superego represents the social norms, values, and moral rules that inform the ego’s decision on how to guide the horse. The superego may be informed by any institution or subject that establishes behavior norms, be it society, a parent, a religious or philosophical model, a political institution, or a self-imposed set of values and morals.

As is the case when riding a horse in real life, the rider (ego) may at times have a good hold on the reins and can successfully guide the horse (id) to where she wants to go, but the force and instinctive drive of the horse is only tamed up to a certain point. At any point, the horse can choose to take its own course leaving the rider no choice and no fighting chance to control the reins.

Ego Defense Mechanisms

When the ego is threatened, offended, or questioned, the unconscious tends to come into play, creating certain behaviors that seek to protect its pride and sense of self. In Freud’s model, these play a big role in how we relate to others, react to conflict, and cope with difficult emotions.

Freud was the first to introduce the ways in which the ego unconsciously defends itself. These are the most commonly referenced defenses in modern psychology:

1. Denial

The refusal to accept a difficult situation. This is often seen in people suffering from addictive behaviors but refuse to see and accept their addiction. Denial is also seen as one of the first steps of coping with the death of a loved one.

Example: Drew has developed an addiction to alcohol that has had detrimental effects on his health, work, and relationships, but when his family brings it up, he insists that everything is fine.

2. Displacement

Changing the target of unpleasant feelings and urges to someone else, normally a less threatening receiver. This is often seen with misplaced anger or frustration.

Example: Marie is upset at her boss for refusing to give her a few days off to take care of her sick child. She doesn’t argue, but later that day, she lashes out at her assistant in an aggressive burst of frustration.

3. Projection

Attributing our own undesirable behaviors or traits to others. Often the traits that we don’t like about ourselves we are quick to spot and judge in others.

Example: Harry complains that his friend is a flake and always cancels plans last minute, but Harry himself has the same habit.

4. Rationalization

Justifying behaviors under a rationale that allows us not to take responsibility for them.

Example: Michelle failed her course in college because she hardly ever showed up to class or studied for her tests. When she sees her failing grade, she insists that her teacher just flunked her because she didn’t like her.

5. Reaction formation

Adopting a reaction contrary to one’s own beliefs to reduce distress.

Example: Tom is annoyed at his coworker who showed up late again because he was up late on a date, but instead of expressing his frustration, Tom listens intently to the details of the date and tells his co-worker how glad he is that he has a good time.

6. Regression

Using coping mechanisms from less mature emotional states, like a tantrum, curling up in bed with a stuffed animal, or anything that in childhood provided safety and comfort.

Example: Every time Maria is feeling anxious, she crawls under her bed as she did as a child when she was afraid.

7. Repression

Unconsciously suppressing the memory of difficult events. Freud proposed that this can often be seen in survivors of traumatic experiences.

Example: Daniel was in a horrible car accident with his family where he lost his younger brother and was severely injured himself, but he has no recollection of the accident itself or the events leading to it.

8. Sublimation

Re-routing socially unacceptable urges or drives into socially acceptable activities.

Example: Stephany often feels bursts of anger that make her want to hurt someone. In order not to act on the urge, she turned to boxing to harness the drive toward a different route.

9. Other Defense Mechanisms

Other less frequently mentioned defense mechanisms that Freud proposed include distortion, splitting, hypochondriasis, passive aggression, dissociation, and phantasy.

All of these mechanisms of defense are an unconscious response to a threatening situation, which is why unless we dive into deeper levels of self-awareness and truthful introspection, we generally remain completely unaware of their presence within ourselves.

Part of Freud’s therapeutic approach was to bring this to light and use them as a tool to explain and understand behavior.

It’s important to note that mechanisms of defense act on a spectrum. They can be adaptive, meaning that they are a tool of the psyche to keep us safe in times of stress with minimal damage, or they can be pathological, which is when these defenses become an obstruction to everyday life and are generally the symptoms and manifestations of a clinical situation.

Freud’s Psychosexual Development Theory

Freud’s work, as mentioned before, had a heavy emphasis on sexuality and sexual drive as a motivating force to most human behavior.

He developed his psychosexual development theory with the belief that humans go through five stages of fixation on different erogenous zones.

He proposed that if these stages of fixation were interrupted or not properly developed, a person could grow to have some sort of maladaptive behavior or fixation involving that particular zone or stage.

The stages of Freud’s psychosexual development theory are:

- The oral stage: Birth until around the first year of age

- The anal stage: 1-3 years old

- The phallic stage: 3-6 years old

- The latent stage: 6 years old to puberty

- The genital stage: Puberty to death

Oedipus & Electra Complex

Freud coined the term “Oedipus complex” as a natural part of human development that happens during the phallic stage.

Named after the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex — where Oedipus, unaware of his birth parents, kills his father and marries his mother — Freud’s Oedipus complex proposed that for a period of his infancy, a boy subconsciously craves a sexual relationship with his mother while generating hostility toward his father.

Freud stated that if the relationship with both parents is smooth and non-traumatic, the complex will resolve itself naturally when the child identifies with his father and represses the impulse.

Jung later introduced the female counterpart of the Oedipus complex: The Electra complex, where similarly, the young daughter unconsciously wants a sexual relationship with her father and seeks to remove her mother. Both Jung and Freud observed the nature of these drives in dreamwork, and later on, Jung would come to see it as a part of the shadow.

Psychoanalysis as Therapy

Freud’s model of helping patients “ease the ills of the mind” was an applied model of psychoanalysis. He used several techniques to bring forth the material of the unconscious mind and use it to help the patient get a better understanding of their own inner world:

Free association

Early in his career, Freud advocated for hypnosis as a method to access the unconscious; however, he quickly shifted to what is now known as free association. In this process, he had his clients talk about the first thing that came to mind (sometimes with a prompt, but most often without) and continue talking without filtering, editing, or trying to make sense of the phrases that came out.

He believed that this practice of free association opened a window into the unconscious and allowed for a deeper level of self-exploration. He also stated that allowing the patient to freely talk encouraged their own conclusions and revelations rather than a prescription by the therapist.

The practice of free association was basically the birth of what we know now as talk therapy.

Dream Analysis

Along with free association, Freud worked with dreams as a way to access material from the unconscious.

Freud’s famous quote states that “the interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” In his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), he summarized his take on dreams and proposed that different kinds of dreams have different purposes and play a role in different processes of the psyche.

His dream work model, which he used as a key part of his work, sought to understand the elements of the dream and their source in reality and the unconscious.

Trauma Recovery Model

The psychoanalytic view on trauma rests heavily on Freud’s theory of repressed memories after a traumatic event. As mentioned earlier, Freud believed that memories that are too hard to bear are repressed by the psyche as a defense and become inaccessible to the conscious mind.

With the use of free association and dream analysis to access the unconscious, Freud sought to help access the repressed memories to create a coherent story of the traumatic event.

Even though the concept of memory repression is controversial in the field of psychology, psychoanalysis even today works under a similar premise seeking to recall or make sense of memories of the event.

Freud Criticism & Rejection

Despite the undeniable influence that Freud has had on modern psychology, he has had a lot of criticism and pushback.

A lot of the lash back against Freud stems from his sexist and non-inclusive approach to psychosexual theories. His stages of psychosexual development are clearly oriented to a cis-gender and heteronormative male collective. This is clearly a product of his own time and upbringing but leaves many flaws for it to be a valid and complete theory that can stand today.

In terms of his career-changing work with “hysterics,” the very nature of his patient’s experiences and his own fixation with the sexual urges of the unconscious creates a breeding ground for malpractice and further abuse and marginalization of women and the denial of their experiences.

It’s important to note that the stories of most, if not all, of his patients in the clinic were plagued with sexual abuse and incest and that the content of sexual encounters with family members that may have been interpreted as an Oedipus complex or sexual fantasy of the unconscious, were actually recounts of traumatizing events.

A big part of modern criticism towards Freud lies in the potential of his theories to normalize these experiences and perpetuate the gaslighting of survivors of abuse.

Many modern experts in the field also argue that none of Freud’s conclusions were arrived at through a proper scientific method and that they mostly represent a subjective report of his own experience and beliefs.

The main subject of this sort of criticism is his theory of repressed memories, which, although still supported by many in the field, has little empirical evidence to back it.

What Was Sigmund Freud’s Stance on Psychedelics?

Although Freud himself never expressed much interest in working with psychedelics to explore the mind, he did have a keen interest in altered states of consciousness and their ability to help us access material from the unconscious.

His work with dream analysis hints at his belief in the potential of altered states as tools of self-awareness.

Freud’s psychoanalysis has played a large role in the beginning stages of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Stanislav Grof, a pioneer in the use of holotropic breathwork who also conducted hundreds of LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) assisted therapy sessions, was interested in Freudian psychoanalysis in his early career and psychedelic experimentation. He proposed an early version of psychedelic-assisted therapy where he combined sessions of full LSD doses followed by psychoanalysis sessions.

Carl Jung’s model of the collective unconscious is now a major component of psychedelic exploration, and his theory of the shadow (which stems from Freud’s theory of the repressed unconscious) has opened the world of shadow work, not only for the fields of therapy and psychology but for anyone who is seeking to gain deeper self-awareness.

It’s no secret that psychedelics induce different states of consciousness, and if we take Freud’s model of the psyche, it would be hard to argue that the use of psychedelics won’t give us some degree of access to the unconscious realm.

Related: 100 Shadow Work Journalling Prompts.

List of Sigmund Freud Books

Sigmund Freud wrote hundreds of books and publications where he thoroughly explored his theories. His publications include case studies from his patients, a wide amount of literary references, and multiple revisions and notes to revise older writings.

Here are some of his most influential books:

- Studies on Hysteria (1895)

- The Interpretation of Dreams (1900)

- The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901)

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905)

- Totem and Taboo (1913)

- On Narcissism ( 1914)

- Introduction to Psychoanalysis (1917)

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920)

- The Future of an Illusion (1927)

- Civilization and Its Discontents (1930)

Sigmund Freud Quotes

Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.”

A man should not strive to eliminate his complexes, but to get into accord with them; they are legitimately what directs his conduct in the world.”

The virtuous man contents himself with dreaming that which the wicked man does in actual life.”

The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.”

People do not really want freedom, because freedom involves responsibility and most people are frightened of responsibility.”

The first human who hurled an insult instead of a stone was the founder of civilization.”

The more perfect a person is on the outside, the more demons they have on the inside.”

The ego is not master in its own house.”

Public self is a conditioned construct of the inner psychological self.”

We are what we are because we have been what we have been, and what is needed for solving the problems of human life and motives is not moral estimates but more knowledge.”

On my way to discovering the solution of the dream all kinds of things were revealed which I was unwilling to admit even to myself.”

Related: Top 100 Quotes on Psychedelics.

Key Takeaways: Who Was Sigmund Freud?

Sigmund Freud was a physician and neurologist who revolutionized the world of psychology. He’s known as the father of psychoanalysis, a model of psychology that seeks to understand human behavior by exploring the psyche and its unconscious drives.

Freud proposed a theory of the architecture of the mind, where he explored the dynamics of the conscious and unconscious mind. Within this model, he introduced the concepts of id, ego, and superego as the main three players in human behavior.

In his work with his patients, Freud dove into dream analysis and free association. He believed that these two techniques were key aspects of understanding the unconscious. Free association is still a staple of psychoanalysis and is a commonly used tool in therapy sessions.

He introduced the idea of the ego’s unconscious defense mechanisms, which are still widely used in modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy.

Although Freud’s work was controversial and his reputation in the medical field took a few blows, much of his work still lies at the base of psychology and the study of human behavior. His work influenced not only the fields of psychology and psychiatry but had a heavy impact on literature, philosophy, and politics as well, and continues to do so today.