What Is the Federal Analogue Act?

In the US, if it looks like something illegal — it’s probably illegal, too.

The law attempts to regulate “designer drugs” by comparing them to controlled substances — but doesn’t offer specific enough criteria to do so consistently. This leads to widespread confusion, particularly in the hemp and psychedelics industries.

This article takes a look at the Federal Analogue Act, explains what it says and what it attempts to do, reviews two important lawsuits, and considers what it means for the cannabinoid and psychedelics industries.

What Is the Federal Analogue Act?

The Federal Analogue Act is a law that bans drugs that are sufficiently similar to illegal drugs.

The law was passed in 1986 as a response to “designer drugs,” which are handcrafted substances made to mimic illegal drugs in order to circumvent bans.

Designer drugs can be more dangerous than the illicit substances they’re meant to mimic and often have higher potency and unpredictable side effects.

The Federal Analogue Act has been the subject of much controversy since it was passed. Most of it stems from a debate about what qualifies a drug as similar enough to an illegal drug. Lawyers and laypeople alike should easily interpret laws in the United States, making phrasing like “sufficiently similar” arguably too vague.

What Did the Federal Analogue Act Aim to Do?

The goal of the Federal Analogue Act was to make it possible to control designer drugs without having to ban each one individually. The legal system is slow by design, making it challenging to stay on top of containing newly produced dangerous substances in a timely manner. It can take years for legislation to work its way through the system, and designer drugs can proliferate during that time.

Designer drugs are dangerous for two reasons. The obvious one is that they produce similar effects to their banned counterparts, which are usually illegal due to having dangerous effects or implications. Sometimes, designer drugs can have more potent effects due to the tweaks made to skirt the law.

Less obvious is that designer drugs can have unintended side effects that bear no resemblance to the original drug. These effects are especially dangerous since users may not recognize the warning signs and could be caught unprepared to respond. If a person’s reaction to a designer drug requires medical intervention, emergency personnel may be unable to help since they don’t know what the drug contains or its typical effects on the human body.

Unfortunately, the law wasn’t as effective as it could have been, largely due to confusion surrounding its vague and confusing wording.

What Is an “Analogue Drug”?

Much of the confusion about the Federal Analogue Act comes from interpreting the word “analogue.” According to the law, an analogue of an illegal drug is one that has a similar chemical structure and function. Quantifying chemical and functional similarity is impossible, leaving it open to interpretation of how similar a designer drug needs to be to fall under the act’s control.

As a result, some comparisons are made in a legal setting based on the effect profile, while others are predominantly based on the chemical structure of the compounds being compared.

The definition of analogue also includes a section covering user intent. This clause is even more nebulous than the clauses that cover chemical and functional similarity, stating that a substance a person intends to use to elicit a similar response to an illegal drug can be qualified as an analogue.

Are Analogue Drugs Illegal?

No, not all analogue drugs are illegal. Vicodin and Oxycontin are considered analogues to heroin but are legal with a prescription. However, they are both illegal without a prescription and are often abused.

Many analogue drugs — like bath salts and K2 — are entirely illegal because they don’t have an officially recognized medical use.

What Are Some Examples of Analogue Drugs?

Here are a few examples of analogues:

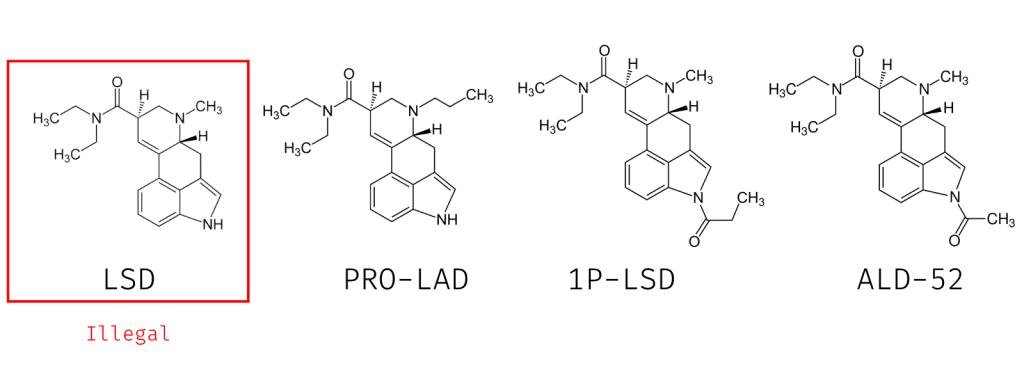

1. LSD Analogs

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is clearly listed as a Schedule I drug in the US and has comparable restrictions in other countries around the world.

But LSD is just one of many compounds considered analogues of each other — including LSZ, ETH-LAD, AL-LAD, PRO-LAD, 1P-LSD, ALD-52, and many others.

The Federal Analogue Act would arguably ban all of these other compounds even though none of them are specifically mentioned on the controlled substances act.

2. DMT Analogs

DMT analogs are a little bit harder to define because many forms of DMT are radically different from each other. It’s less clear where the line is that deems a given compound to be considered an analog of N,N,DMT, or 5-MeO-DMT — which are the only two listed as controlled substances in the United States.

Potential analogs of DMT include 4-AcO-DMT, bufotenin, and 5-Bromo-DMT.

3. THC Analogs

There were a ton of THC analogs on the market prior to the introduction of the Federal Analogue Act. Many of these compounds have been proven to be harmful, addictive, and even lethal.

The main problematic analogs of delta 9 THC are the non-classical cannabinoids — which means they activate the cannabinoid receptors but didn’t meet other criteria to be deemed a cannabinoid.

Arguably, these compounds could be different enough on their own to sidestep the Federal Analogue Act.

However, a few of them have been added to the list of controlled substances, which then enabled all of their direct analogs to become illegal as well. This includes compounds such as JWH-007, JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, JWH-398, AM-1221, AM-2201, AM-694, and WIN-55,212-2.

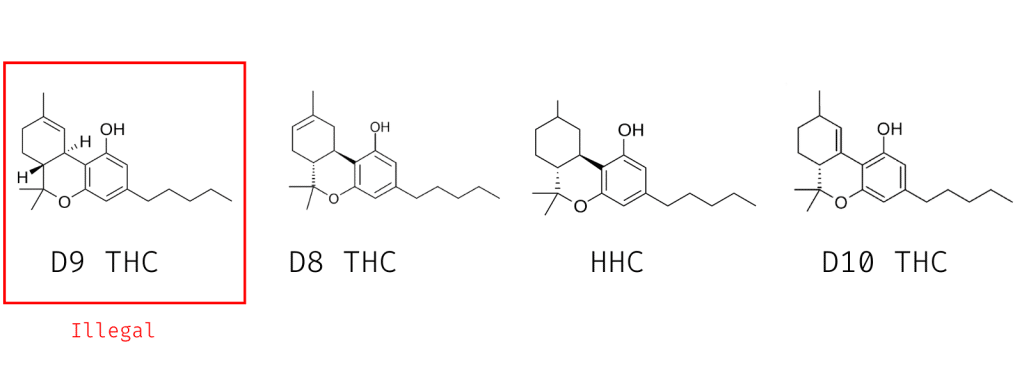

True THC analogs include delta 8 THC, delta 10 THC, HHC, THC-O, and THCP.

Loopholes in the Federal Analogue Act

It is becoming more common for analogue drugs to find a foothold in the recreational drug community, even if they aren’t successful at circumventing the Federal Analogue Act. Examples include bath salts, spice, and K2, all of which are powerful psychoactive drugs that aren’t specifically illegal.

Some daring proprietors attempt to sell synthetic cannabinoids like spice and K2 by labeling them not for human consumption.

The term “bath salts” came from vendors selling synthetic cathinones as “bath salts” because of their similarities in appearance.

Giving compounds a nickname or suggesting they are “not meant for human consumption” isn’t enough to avoid the restrictions put in place by the Federal Analogue Act. The very sale of these compounds, regardless of their intended purpose, is illegal.

The loopholes come down to whether or not someone can convince a judge that the compound they’re selling is different enough from compounds listed on the controlled substances act. If it’s different enough that it can’t reasonably be considered an analog drug, it could be considered legal by proxy.

Notable Cases Regarding the Federal Analogue Act

There have been several prominent legal battles over-interpreting the Federal Analogue Act that have set some precedent for future rulings. Here is a look at two of them.

1. United States v. Forbes

In 1992, Colorado district courts deliberated on whether a drug called alphaethyltryptamine (AET) was sufficiently similar to dimethyltryptamine (DMT) to be considered an analogue. The court ultimately concluded that it could not be considered a DMT analogue based on three main factors.

First, AET is a primary amine, while DMT is a tertiary amine, meaning the drugs do not have the same chemical structure. Although no clear definition of “similar” is given in the Federal Analogue Act, the Colorado district court deemed these differences sufficient.

Second, AET cannot be created from DMT, further emphasizing their different structure. There is no stipulation establishing the ability to synthesize an analogue from the drug it’s based on as a criterion. In this case, that point apparently played an important role, according to court records.

Finally, the court ruled that AET does not have substantially similar psychoactive effects to DMT to be classified as a DMT analogue.

The court commented that, ultimately, the decision to rule that AET was not an analogue of DMT came down to vagueness. The ruling included a recommendation that the Federal Analogue Act be revised to increase its clarity and specificity.

In light of this decision, AET was scheduled separately.

2. United States v. Washam

A 2002 case, United States v. Washam, is an example where the court decided that the drug in question was substantially similar to the controlled drug it was being compared to.

This case was in the eighth judicial circuit and was centered around whether 1,4-butanediol (1,4-B) was similar enough to the controlled substance gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) to qualify as an analogue.

The court decided that 1,4-B and GHB were structurally similar since both are linear molecules consisting of four carbon atoms. It was also decided that the two drugs were functionally similar since 1,4-B is metabolized into GHB in the body.

Interestingly, this case mirrored United States v. Forbes, stating that the Federal Analogue Act is unconstitutionally vague. However, this case upheld the Federal Analogue Act and set a precedent for it to be enforced.

Interpretation of the Federal Analogue Act

The previous two cases demonstrate how difficult it can be to interpret a law like the Federal Analogue Act. Without precise language and quantitative metrics to fall back on, it is difficult to predict what decision a court will reach since there are many ways to parse the terms “substantially similar.”

By contrast, the 2018 Farm Bill that legalized hemp-derived cannabinoids specifically stated that cannabis plants containing less than 0.3% THC by volume were categorized as hemp legal under federal law. While the wording in the Farm Bill is clear and precise, the Federal Analogue Act could conceivably be used to argue that several cannabinoids like delta 8 THC and delta 10 THC should be illegal since they’re technically analogues of delta 9 THC.

As of this writing, it is unclear whether the 2018 Farm Bill supersedes the Federal Analogue Act, but most people agree that it does. Delta 8 THC, delta 10 THC, and other minor cannabinoids are legal in many parts of the United States, and so far, there haven’t been any prominent cases that attempt to use the Federal Analogue Act to ban them.

An additional important point is that states are free to set and enforce their own laws, regardless of federal policies. Some states have instituted bans or restrictions on cannabinoids, something they can do without appealing to the Federal Analogue Act, which operates at the federal level.

Wrapping Up: The Significance of the Federal Analogue Act

The Federal Analogue Act attempts to regulate designer drugs so that lawmakers don’t need to ban synthetic versions of illicit drugs individually. Unfortunately, its usefulness is hampered by confusing, vague wording that makes it difficult to interpret.

Two major court cases have attempted to use the Federal Analogue Act to illegalize substances, one successfully and one unsuccessfully. The cases are similar to an untrained eye, and the opposite decisions add to the confusion. Both cases encouraged legislatures to rework the law to make it more transparent.

Cannabinoids like delta 8 THC and delta 10 THC are left in legal limbo by the competing forces of the Federal Analogue Act and 2018 Farm Bill. The Federal Analogue Act appears to indicate that they should be banned due to their similarity to the controlled substance delta 9 THC, while the Farm Bill explicitly legalizes them at the federal level.