The Science of Psilocin: The Active Compound In Magic Mushrooms

Most mushrooms only contain trace amounts of psilocin, but it still contributes to the magic ✨

In 1959, Albert Hofmann and a team of researchers cracked the code of the mushroom. They determined the main components of the hallucinogenic drugs were psilocybin and psilocin, noting the latter was present only “in trace amounts” [1].

While psilocin is often only present in negligible quantities, our metabolism converts psilocybin into psilocin after consumption. Psilocybin plays a crucial role by being more stable, but it exists solely as a prodrug for its active metabolite.

Let’s discuss this process and what makes this molecule so interesting.

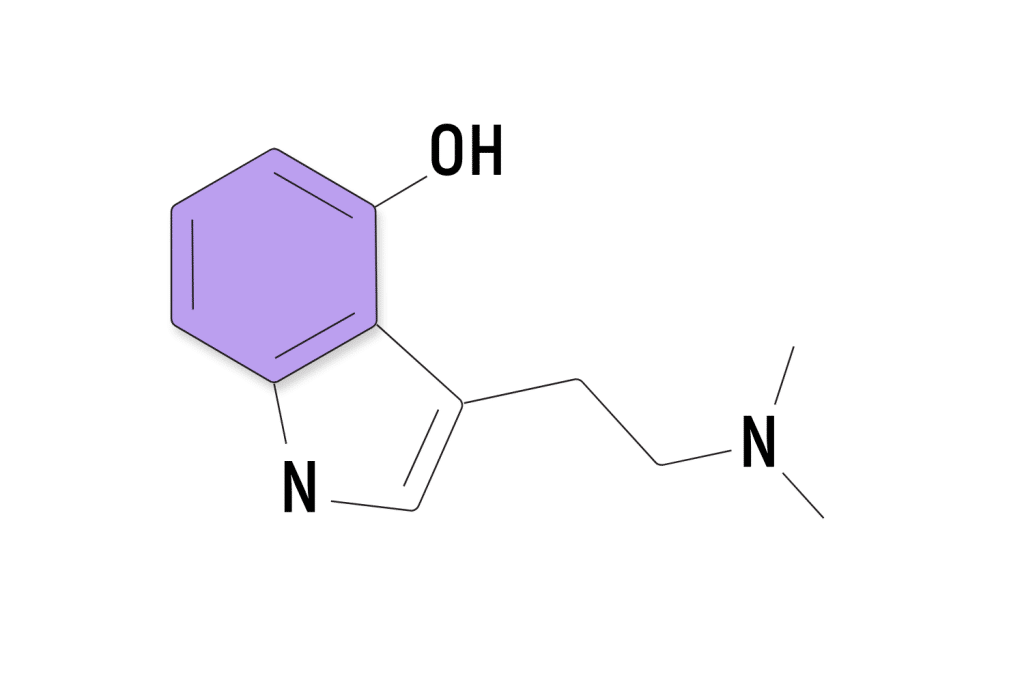

Molecular Makeup of Psilocin

4-hydroxy-n,n-dimethyltryptamine (4-HO-DMT) — psilocin — occurs naturally in magic mushrooms and as a metabolite of psilocybin. As PubChem describes it: “Psilocin is a tryptamine alkaloid that is N,N-dimethyltryptamine carrying an additional hydroxy substituent at position 4.”

This addition makes psilocin orally active and creates a drastically different experience from DMT (N,N,dimethyltryptamine). DMT without this component immediately metabolizes into inactive compounds thanks to our digestive monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes.

A hydrogen bond pulls the ends together to form a barrier protecting it from the degrading actions of MAO enzymes [2]. There are two ways we consume this molecule — as is and through its naturally-occurring prodrug, psilocybin.

After consuming mushrooms, psilocybin loses a phosphate group — the process of dephosphorylation — converting to psilocin. It can easily cross the blood-brain barrier from here, causing the effects we know and love.

Pairing psilocybin-containing mushrooms with an MAOI — “psilohuasca” — shows psilocin still undergoes some degradation, however. Inhibiting the MAO enzyme amplifies the effects of magic mushrooms by as much as 4x, depending on the subjective report.

Due to this, it appears as though psilocin is much more resistant to the enzyme but may still lose some potency due to it.

Is Taking Psilocin Different From Psilocybin?

There’s little research on how taking these two different — yet similar — molecules compare. Subjective reports indicate psilocin has a faster onset, a more intense experience, and a heavier effect on movement than psilocybin.

Whether these are true experiences or only perceived differences is yet undetermined, but one team of researchers is working on getting to the bottom of it. Dr. Joshua Woolley of the University of California, San Francisco, has a study underway to determine if there is a difference.

In the study, Dr. Woolley and his team will randomize 20 healthy participants into three groups:

- Sublingual Psilocin — Since psilocin doesn’t need to undergo metabolization, this will determine if psilocin can enter the bloodstream and cross into the brain directly through the mucosal membrane.

- Oral Psilocin — To determine the effects of taking the molecule orally without the need for dephosphorylation.

- Oral Psilocybin — Since psilocybin relies on the metabolic process, sublingual isn’t an option, but oral psilocybin can provide a baseline for the typical experience with magic mushrooms.

Dr. Woolley laid out their anticipated results in an episode of the Psychedelic Medicine Podcast. While many potential findings could flow from this, the sublingual use of psilocin may be the most exciting.

As Dr. Woolley put it, “it doesn’t have to go to the liver, and it might be faster that way and maybe again more consistent. And fewer side effects — maybe you won’t get any GI side effects if it doesn’t go to the GI tract.”

This will be the first study of its kind and may determine the standard for researchers going forward. It could have profound implications if one can prove more reliable or measurable than the other.

Related: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin (Differences & Similarities Explained)

The History of Psilocin

We’ll discuss the indigenous use of this molecule later, but for now, we’ll talk about psilocybin’s modern history.

Its story starts when Albert Hofmann and his team discovered, isolated, and named the molecule in 1958. This was a triumphant success for science at the time — finding the scientific reason for certain cultures’ spiritual relationship with magic mushrooms.

Hofmann was also the scientist who created lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and discovered its potential 20 years earlier. Though many refer to him as the “father of LSD,” he had his hands on many psychedelics and advanced the science of multiple substances.

It took another 40 years for scientists to perfect the ability to synthesize psilocybin on a large scale. Osamu Shirota and his colleagues, who were working at the National Institute of Health Sciences in Tokyo, get credit for cracking the code [3].

It wasn’t until 2017 — nearly 60 years after the compound was first discovered — that we understood how the mushroom produces it [4]. This knowledge has helped researchers manipulate other microorganisms to produce large quantities of psilocybin and psilocin [5].

Psilocin Research: What Are the Benefits?

Research was in full force on psilocybin and psilocin when the government first created the Controlled Substances Act and outlawed them. Luckily, they’re becoming much easier for researchers to get now.

As a result, a host of new studies on the potential benefits have taken off. Most research focuses on using psilocybin as a way to measure dosage, but since psilocin is the active metabolite, they’re all effectively studying this.

Here are some of the most important areas of research in the field of psychedelic mushrooms

Psilocin & Depression

A 2021 study of a small group of people found psilocybin, along with therapy, had a significant effect on Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [6]. MDD has been elusive and difficult to manage since we still have only a small grasp on the issue of depression.

On top of being more difficult to manage, MDD is also often treatment-resistant — meaning it is not responsive to current treatment options. Though this study utilized a small sample size, the results are promising, and a lot more is coming up around this concern.

Most solutions typically show little success in treating MDD, but researchers noted that 71% of participants saw a “clinically significant response to the intervention” after four weeks. Even more impressive, 54% were in remission at the four-week mark.

The sample size alone leaves a lot of room for further study, but this is exciting regardless.

Related: Medicine for the Mind: Psychedelics for Depression & Mental Illness

Psilocin & The Mystical Experience

Many people treat psychedelics as an easy, one-stop solution for treatment, but the most successful experiences with psychedelics involve lifestyle changes after the trip.

One study found meditation and spiritual practice are determining success factors — and that psychedelics like psilocybin (and subsequently psilocin) help initiate spiritual experiences [7].

Participants who took one or more large doses of psilocybin and maintained healthy spiritual practices showed “significant positive changes on longitudinal measures” of the following:

- Interpersonal closeness

- Gratitude

- Life meaning and purpose

- Forgiveness

- Death Transcendence

- Daily Spiritual experiences

- Religious faith and coping

- Community observer ratings

In all cases, the two factors determining success were the dose size and the participants’ practices after. This is an interesting direction for psychedelic studies — determining how our overall lifestyle can determine the outcomes of our experience.

Mystical Experiences & Their Meaning

One study in 2006 sought to explain the feelings behind psychedelic experiences and how they compare to spontaneous mystical experiences. Thirty adults who reported regularly practicing religious or spiritual activities but had never tried the drug volunteered for the study.

Researchers found “supportive conditions” when administering psilocybin could result in effects “similar to spontaneously occurring mystical experiences” [8]. This was still true at the 2-month follow-up, showing potential for lasting effects.

The prospect is for scientists to have an easy, reliable way to research these feelings, what causes them, and how they affect us.

We’ve never had a good way to look at them before now. This study shows the role of meditation, along with psychedelics, and the importance of spirituality.

Psilocin & Existential Anxiety

One of the most popular studies for psilocybin and psilocin involved a group of participants with terminal cancer [9]. As an introduction to the topic, this study had very few participants — 12 in total.

The aim was to see if the patients could find peace with their diagnoses and likely deaths. Though it was just a start, the results were promising, and the use case was interesting.

More research is likely in the upcoming years, but one victory is that a number of states have enacted “right to try” laws. These legislative changes allow terminal patients in these states to try any drug beyond phase 1 trials.

Outside of the fact that little harm can come to a person already suffering from a life-ending illness, this gives individuals the right to try riskier drugs in hopes they might help. Another benefit is the ability to try psilocin and other psychedelic drugs to face the existential anxiety often looming overhead.

Psilocin & Anxiety Disorders

Giving up control to the extent required for a psychedelic experience may sound daunting for someone dealing with anxiety. Researchers are finding it’s potentially the missing key to unlocking treatment for this condition.

In another study with cancer patients, psilocybin was found to reduce depression and anxiety “substantially and for a long time” [10]. Unlike depression or anxiety medications, which require daily use to work, this was a treatment with potential longevity after one dose.

This randomized, double-blind trial was still small, with only 56 total participants and 24 taking two doses of psilocybin. Results indicated an 80% success rate in “continuing to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety.”

Results remained steady after a 6-month follow-up, indicating a lasting effect. While there is a myriad of unanswered questions, this gives a glimmer of hope for many.

Historic & Indigenous Use of Psilocin & Magic Mushrooms

In many ways, psilocin has a history more storied than we could ever present in a single article. The whole story of the mushroom’s hallucinogenic component would have to go back thousands of years.

Partly because of the extreme length of time psilocybin has been in use and partly due to brutal colonization efforts that destroyed historical artifacts, we don’t know how far back mushroom use goes. However, we do know the “Stoned Ape Theory” by Terrance McKenna is getting some scientific traction.

The idea behind this theory is that psilocybin-containing mushrooms may have helped the people who came before homo sapiens evolved. Several historical studies have found evidence that mushroom use may have been pivotal in our story [11].

This probably went on for hundreds of years until colonization tried to wipe out other religions and ways of life. There are still a few places in the world honoring the mushroom, but they often have to do so in near-isolation or change as they become tourist spots.

As legalization efforts progress, a growing voice advocates for a thoughtful approach to the indigenous use of psychedelics. Part of this involves calling out the appropriation of rituals, and almost all of it comes down to a lack of education, understanding, and openness.

Related: The History of Psychedelics

Using Psilocybin/Psilocin Responsibly

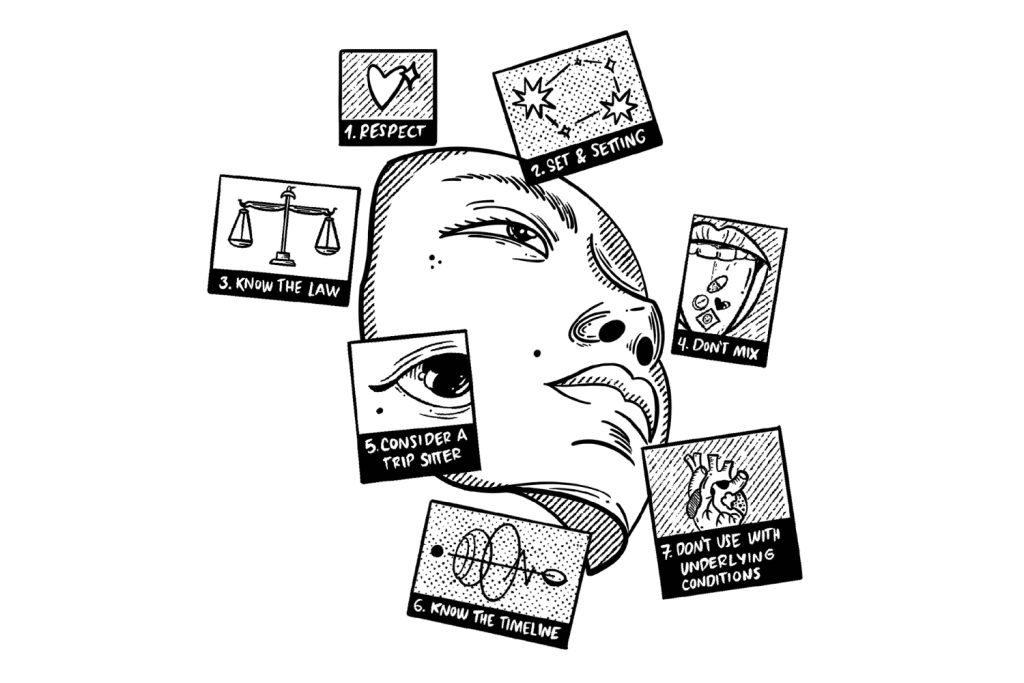

Bad trips can happen to anyone anytime, but there are several ways to minimize the risk before and during your trip.

Below is a checklist you should go through before participating in a psychedelic experience:

- Respect — Whether it is your first time or your 1000th, you should always approach these substances with respect and reverence.

- Set and Setting — Intentionally setting your goals and preparing your mind for the experience is crucial, as is the location of the trip and how clean and safe it is.

- Know the Law — Every state and country can set its own laws and expectations for magic mushrooms. Be familiar with the laws and regulations in your current location.

- Don’t Mix — You shouldn’t mix psilocin with any other drugs or substances, including prescribed medication.

- Consider a Trip Sitter — Have someone nearby who is sober and can help; this can be a lifesaver.

- Know the Timeline — Psilocin and psilocybin can take upwards of an hour to take effect and may last as long as 6-8 hours, depending on the dose.

- Don’t Use With Underlying Conditions — Particularly heart, psychiatric, and neurological conditions.

Summing It Up: What Is Psilocin?

Psilocin is a phenomenal molecule that contains the entire spectrum of the mushroom experience. While we often speak of psilocybin when referring to these, it’s not the real star of the show.

Rather, psilocybin is a precursor to psilocin, converting in the liver shortly after ingestion. Psilocybin is more stable than psilocin and likely acts as an evolutionary bolstering of the chemical since it has a longer shelf-life.

When it comes to magic mushrooms, only discussing psilocybin shows half the picture. Psilocin is a critical element of the hallucinogenic experience and deserves full respect.

References

- Hofmann, A., Heim, R., Brack, A., Kobel, H., Frey, A., Ott, H., … & Troxler, F. (1959). Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 42(5), 1557-1572.

- Lenz, C., Dörner, S., Trottmann, F., Hertweck, C., Sherwood, A., & Hoffmeister, D. (2022). Assessment of Bioactivity — Modulating Pseudo‐Ring Formation in Psilocin and Related Tryptamines. ChemBioChem.

- Shirota, O., Hakamata, W., & Goda, Y. (2003). Concise large-scale synthesis of psilocin and psilocybin, principal hallucinogenic constituents of “magic mushroom”. Journal of natural products, 66(6), 885-887.

- Fricke, J., Blei, F., & Hoffmeister, D. (2017). Enzymatic synthesis of psilocybin. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 56(40), 12352-12355.

- Milne, N., Thomsen, P., Knudsen, N. M., Rubaszka, P., Kristensen, M., & Borodina, I. (2020). Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the de novo production of psilocybin and related tryptamine derivatives. Metabolic engineering, 60, 25-36.

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., May, D. G., Cosimano, M. P., Sepeda, N. D., Johnson, M. W., … & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 78(5), 481-489.

- Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., Jesse, R., MacLean, K. A., … & Klinedinst, M. A. (2018). Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(1), 49-69.

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268-283.

- Grob, C. S., Danforth, A. L., Chopra, G. S., Hagerty, M., McKay, C. R., Halberstadt, A. L., & Greer, G. R. (2011). Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Archives of general psychiatry, 68(1), 71-78.

- Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Carducci, M. A., Umbricht, A., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., … & Klinedinst, M. A. (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1181-1197.

- Rodríguez Arce, J. M., & Winkelman, M. J. (2021). Psychedelics, sociality, and human evolution. Frontiers in Psychology, 4333.