Making Sense of Psychedelic Research

We’re about to enter the golden age of psychedelic research. Here’s a snapshot of where we’re at in 2022.

Psychedelic research reached its zenith in the early 1960s. Over 1000 articles exploring psychedelics as a psychiatric treatment were published in the 50s and 60s, involving more than 40,000 participants [1].

After just a short (but promising) stint of research and some unscrupulous practices by the federal government, psychedelics were eventually banned by the Nixon administration in 1968.

This brought research to an abrupt halt — where it remained for nearly 30 years.

Today, after decades of prohibition and a now failed war on drugs, psychedelic research is picking up where it left off.

Here, we’ll examine the current state of psychedelic research. We highlight some of the top research for various psychedelic plants, fungi, and synthetic molecules, break down the motivations for this research, and give kudos to some of the biggest influencers in the academic investigation of mind-altering substances.

An Overview of Psychedelic Research

- Early research (the 50s and 60s) was focused on understanding the effects of psychedelics — primarily mescaline, LSD, and psilocybin.

- Research picked up again in the late 90s — primarily applying neuroimaging and animal research to understand the mechanisms of action & safety profile for various psychedelics.

- Numerous high-level institutions now have dedicated psychedelic research departments, including Johns Hopkins, UC Berkely, NYU Langdone, and several others.

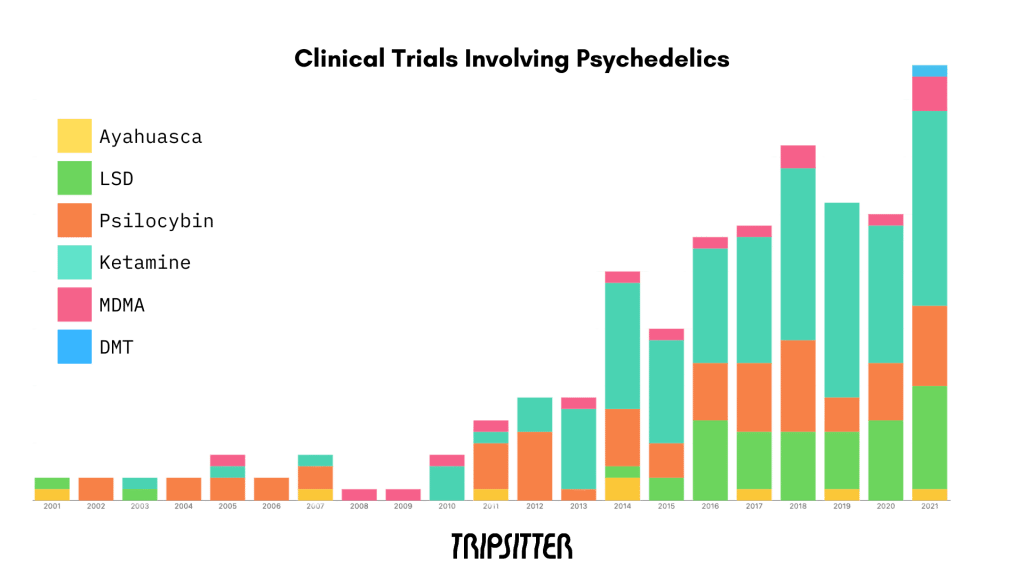

- The most researched psychedelics are MDMA, psilocybin, & ketamine — accounting for more than 50% of the clinical research on psychedelics to date.

- There are more than 50 biotech startups operating in the psychedelic space, now worth more than $10 billion combined.

- Globally, there are 82 active phase II trials with psychedelics, of which 45% are completed.

Psychedelic Research Over the Years

The start of modern psychedelic research stems from a trip to Mexico by a wealthy banker by the name or R. Gordon Wasson. Wasson and his wife took some psychedelic mushrooms given to him by a local shaman, which he brought back to America for further investigation amongst his colleagues. A sample was sent to the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann (also the creator of LSD), who was able to identify, isolate, and synthesize the active ingredient, psilocybin.

Around the same time, Wasson published an article in LIFE Magazine detailing his experiences with the strange mushrooms. This article went on to inspire many of the great psychedelic explorers of the time, including Alexander Shulgin and Timothy Leary.

After reading the article and traveling to Mexico to explore these mushrooms himself, Leary, a professor at Harvard University, set up the first institutional psychedelic research department along with his colleagues Richard Alpert, Aldous Huxley, David McClelland, Frank Barron, and Ralph Metzner. The program was dubbed “The Harvard Psilocybin Project.”

After just a few years of “research” — which mainly involved dosing friends, grad students, and colleagues with LSD and psilocybin to “see what happens” — the program was eventually shut down.

Around the same time, the CIA was studying psychedelics for their potential role in dubious activities like mind control or interrogation. The secret name for this project was called MK-ULTRA, which was later declassified in 2001. This research, along with the growing counterculture movement that was particularly fond of psychedelics, led then-president Nixon to ban all use, research, or mention of LSD in 1968 and later added psilocybin and several other compounds two years later.

After three long decades of radio silence, the pulse on psychedelic research finally began to beat once more. For the first time in several decades, the NIH approved a research program involving DMT led by University of New Mexico researcher Rick Strassman. Strassman conducted human research on the compound from 1990 to 1995 — eventually publishing a summary of his work in the book DMT: The Spirit Molecule.

Five years after Strassman completed his research, the Obama administration passed a bill that allowed psychedelics to be used for research purposes again, which opened the doors for many eager researchers to dive back into this promising field of psychiatric research. The first major studies through the gate came out of places like Johns Hopkins with their infamous 2006 psilocybin study led by Roland Griffiths.

The field of psychedelic research is now alive and well. Every year, hundreds of articles are published exploring different facets of psychedelics, including dozens of high-level clinical trials.

Research is being funded by government organizations, biotech startups, wealthy philanthropists, and various institutional grants.

Areas of Focus in Psychedelic Research

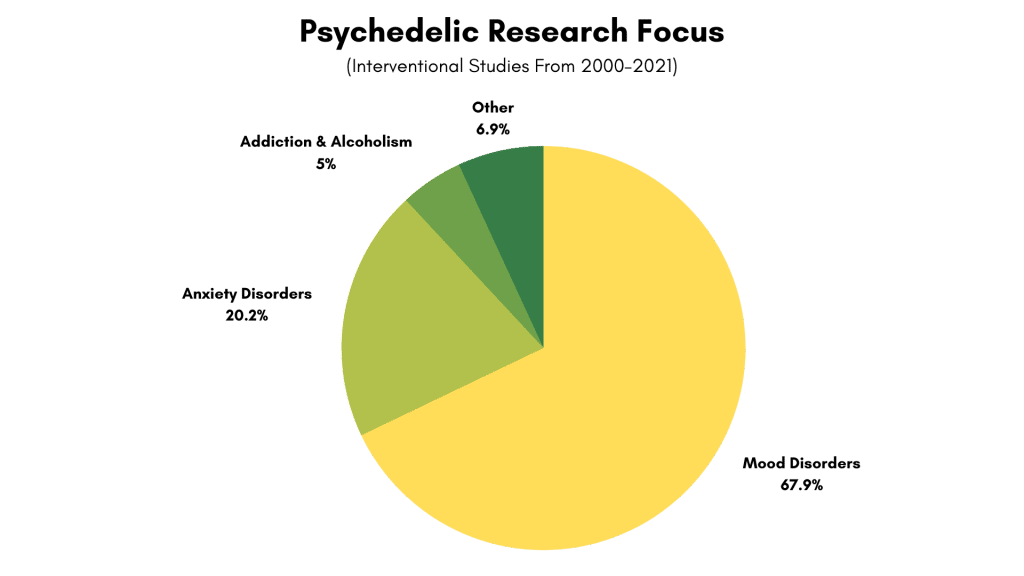

The recent wave of interest in examining psychedelic substances spans a wide range of topics and focus points, but there are a few prominent areas that stand out.

By far, the two psychedelics with the most attention are psilocybin and MDMA. Both are being explored as a potential treatment for depression and PTSD in phase I, II, and III clinical trials. All of the prominent psychedelic research institutions listed below are investigating either one or both of these compounds in greater detail.

Other psychedelics with strong interest are ketamine for treatment-resistant depression, LSD and psilocybin for cluster headaches, and DMT or ibogaine for addiction.

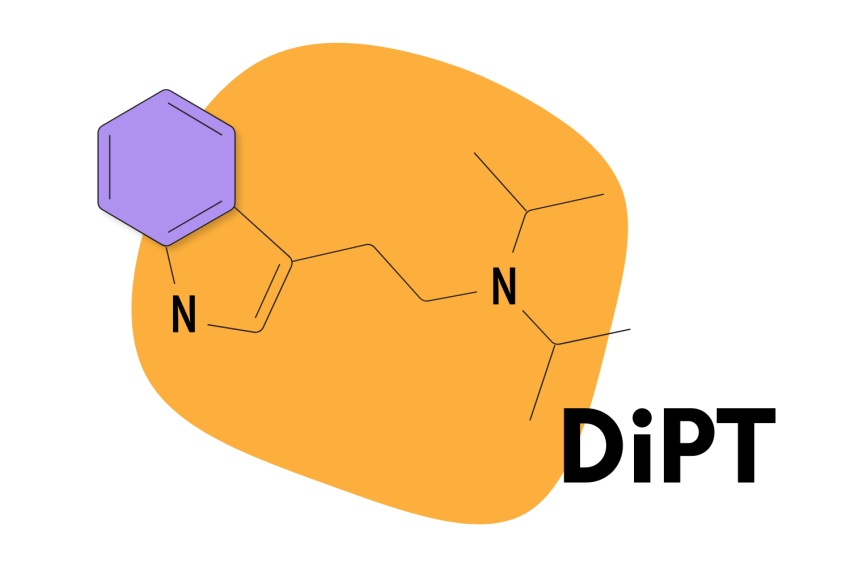

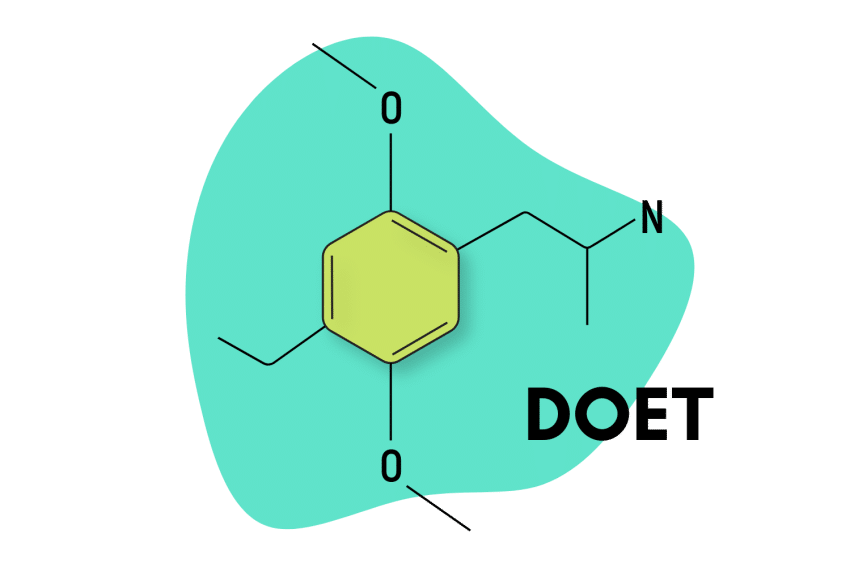

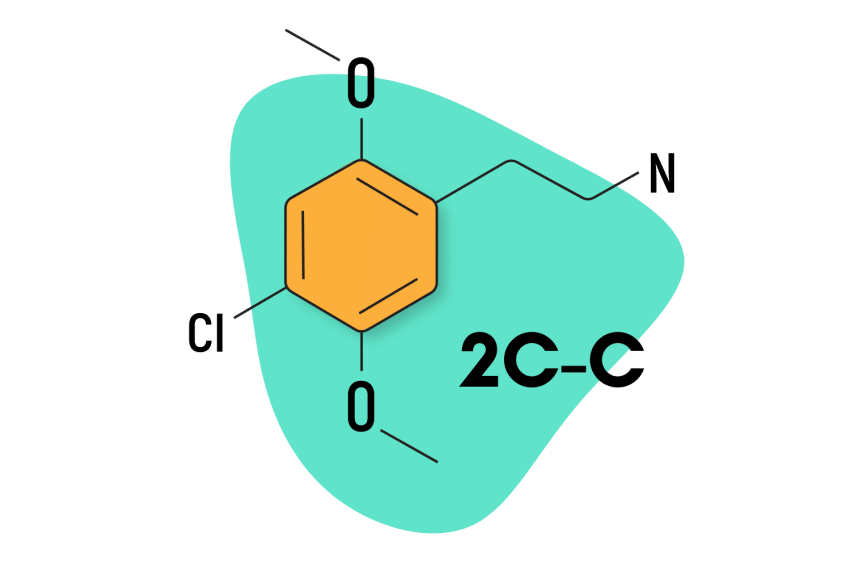

Biotech companies are primarily focused on products that can be patented — such as new delivery methods for administering ketamine or psilocybin or new psychedelic compounds like 18-MC (MindMed) or GH001 (GH Research Ireland).

There are three key areas of focus when it comes to psychedelic research:

- Addiction & Alcoholism

- Anxiety Disorders (Including Existential Anxiety & PTSD)

- Depression & Mood Disorders

Other areas of focus involving psychedelics include consciousness research, neuropharmacology, and the application of psychedelic compounds for enhancing problem-solving and creativity, treating chronic pain, cluster headaches, and supporting patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit disorders (ADD/ADHD).

Below is an analysis of over 208 interventional clinical studies in our database and their primary areas of focus:

Note: This analysis covers interventional studies only (studies aiming to assess the effectiveness of a drug for treating a specific medical condition). There are thousands of other clinical trials that have been published on healthy volunteers to assess safety, understand neuropharmacological changes, and much more.

Psychedelic Substances in Focus

There are thousands of known psychedelic substances, but the research tends to focus most heavily on just a few of them.

Most psychedelic research focuses on psilocybin, MDMA, LSD, ayahuasca, ketamine, and iboga.

Here’s what the research looks like for these common substances so far:

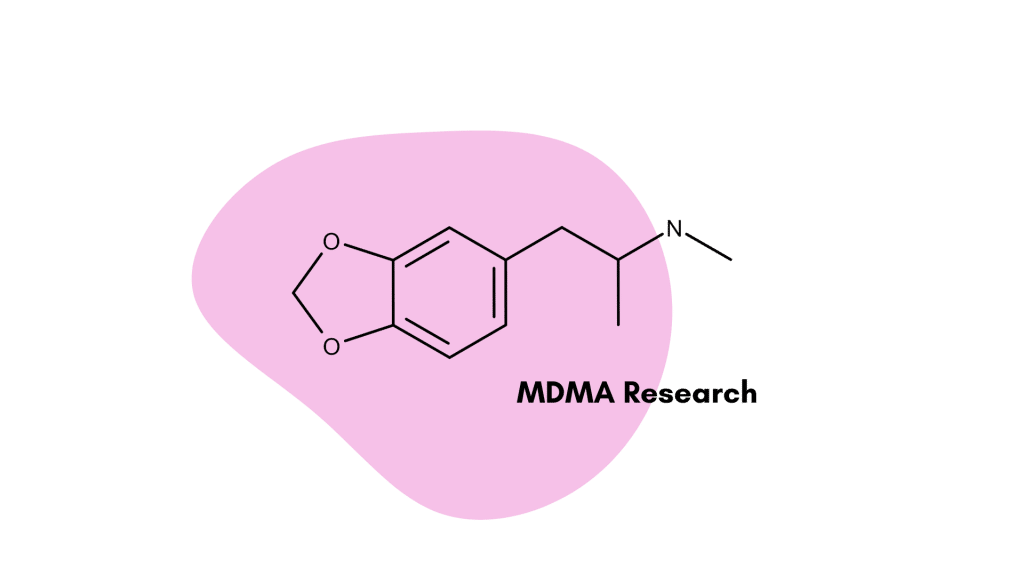

1. MDMA Research

Most of the clinical research on MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) has been funded and organized by MAPS and University Hospital in Basel, Switzerland.

So far, research strongly supports the use of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and preliminary findings suggest it may be helpful for dissolving barriers between therapists and their patients.

MAPS first clinical trial was published in 2010, which explored the efficacy of using MDMA in the treatment of PTSD. This study was a breakthrough in the field of MDMA research — resulting in a clinical response rate of over 80% (compared to 25% in the placebo control group).

Over the following years to the present day, MAPS has conducted several clinical trials examining the effects of MDMA on PTSD, social anxiety, substance abuse, and existential anxiety. MAPS is currently working on a phase III clinical trial on the application of MDMA for the treatment of PTSD, which is scheduled to complete sometime in 2023.

The University Hospital in Basel has been conducting its own studies on MDMA, covering topics related to MDMA-drug interactions (Pindolol, Duloxetine, Modafinil, Clonidine, Reboxetine, Carvedilol, Doxazosin, Methylphenidate, and many others), as well as the effects on emotional processing, and fear extinction.

Prominent Clinical Research on MDMA:

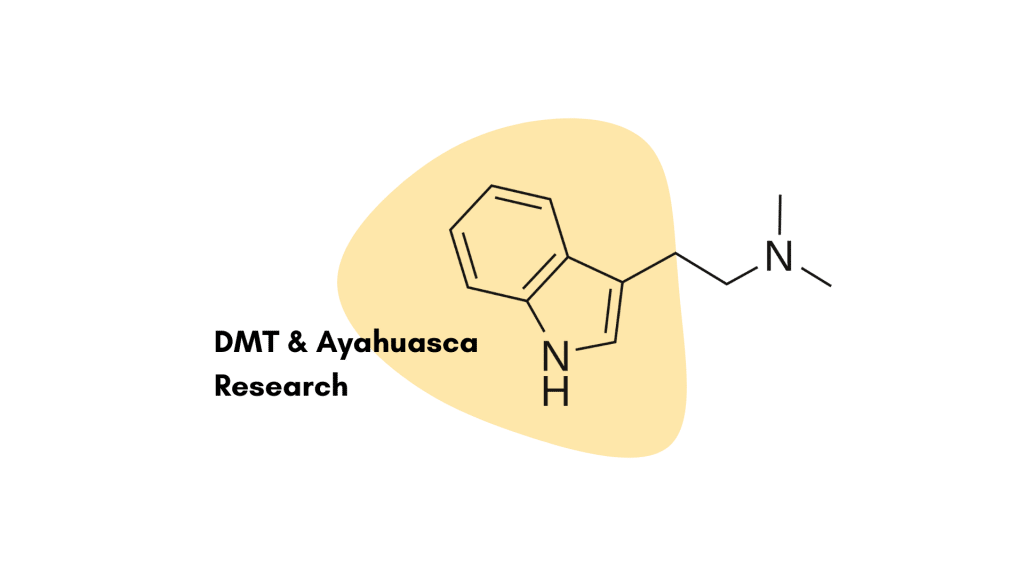

2. DMT & Ayahuasca Research

Research on DMT started off slowly. It wasn’t an area of focus in the early wave of psychedelics in the 1950s and 60s. A few studies were published in the 1970s examining various methods of identifying DMT in blood or urine samples and elucidating its chemical structure.

It wasn’t until the year 1990 when Dr. Rick Strassman began his groundbreaking clinical research on DMT. For five years, Strassman and his team sought to understand the effects of N,N,DMT on human subjects. Over the course of his studies, he administered approximately 400 doses of DMT to nearly 60 volunteers.

Strassman’s research also led to the development of the Hallucinogen Rating Scale (HRS), which is still used in psychedelic research today to obtain qualitative information on the psychedelic experience.

Strassman later published his book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, in 2000, which summarized his findings. This book is the best place to start for anybody interested in learning more about DMT and psychedelics.

There have also been several studies examining the effects of ceremonial ayahuasca consumption on existential anxiety, depression, addiction, mindfulness, memory, and more.

Today, most of the recent clinical trials involving DMT focus on an analog called GH001 (5-MeO-DMT made by GH Research Ireland Ltd). Studies are currently entering phase II clinical trials for the treatment of depression.

Another preparation, called BPL-003 (5-MeO-DMT) made by Beckley Psytech Ltd., is recruiting for the first round of phase I clinical testing.

Prominent Research on Ayahuasca & DMT

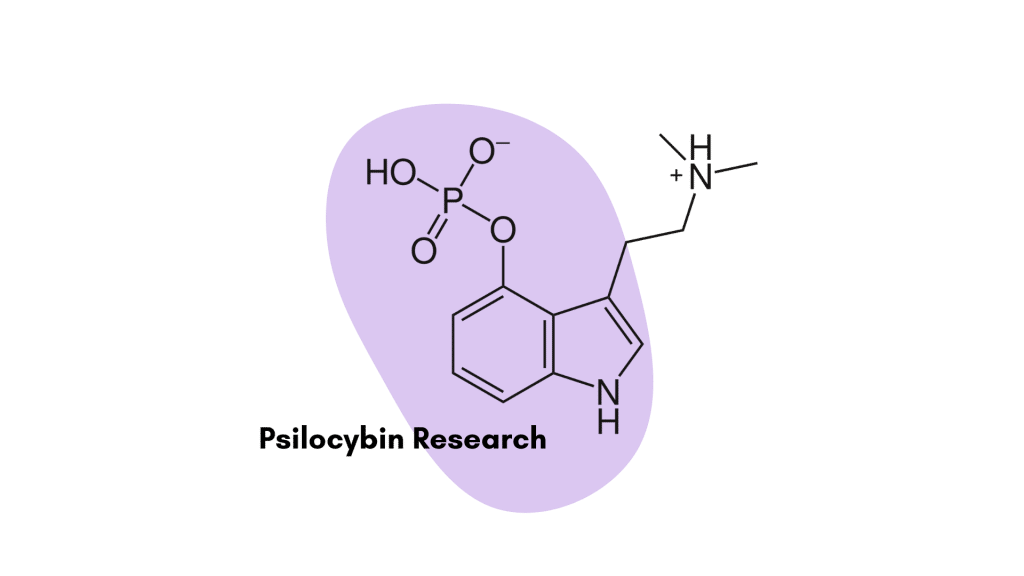

3. Psilocybin Research

Virtually all research institutions are working on psilocybin at this point — largely funded by private companies and philanthropic donors. There have already been dozens of clinical trials exploring the efficacy of psilocybin for depression, addiction, anxiety, pain, and much more.

Johns Hopkins has been especially active in performing interventional studies on humans using psilocybin and other psychedelics. Early work by Matthew Johnson, Roland Griffiths, and other members of the JH faculty involved laying out protocols and review papers examining the safe and responsible use of these compounds.

Griffiths has published studies on the effects of psilocybin in the treatment of existential anxiety and mystical experiences. Johnson has been studying the use of psilocybin for smoking cessation and other forms of addiction, cancer distress (a specific form of existential anxiety), and PTSD.

This research has led the team at Johns Hopkins Center For Psychedelic & Consciousness Research to officially call on the DEA to reclassify psilocybin from its current Schedule I status (which constitutes substances with no known medical potential) to a Schedule IV drug (substances with confirmed medical use, but stronger limitations for use).

Related: What’s The Current Legal Status of Psilocybin Mushrooms?

Today, venture capital-backed companies like Compass Pathways, Atai Life Sciences, MindMed, Field Trip Health, Numinous Wellness, and various others have been investing heavily in clinical testing of both natural and synthetic psilocybin and psilocin. For example, Compass Pathways recently completed a phase IIb clinical trial on the use of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression (COMP 360 TRD) and is currently recruiting for another phase II trial on PTSD (COMP 360 PTSD).

Psilocybin Research Summary:

- Areas of Research Focus: Existential anxiety, depression, addiction.

- Major Sponsors to LSD Research: Compass Pathways, Johns Hopkins, UC Berkely, MAPS, University Hospital (Basel, Switzerland)

- Psilocybin Pipeline:

Prominent Research on Psilocybin & Psilocin:

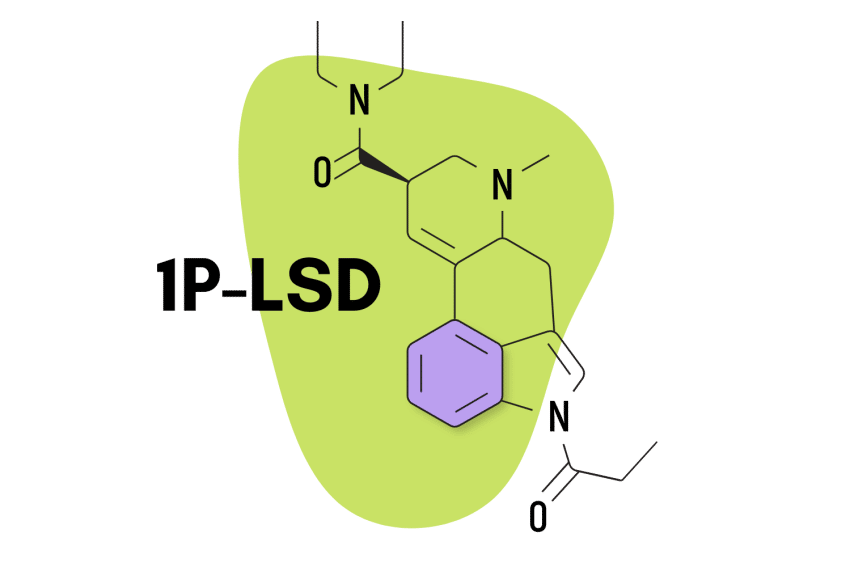

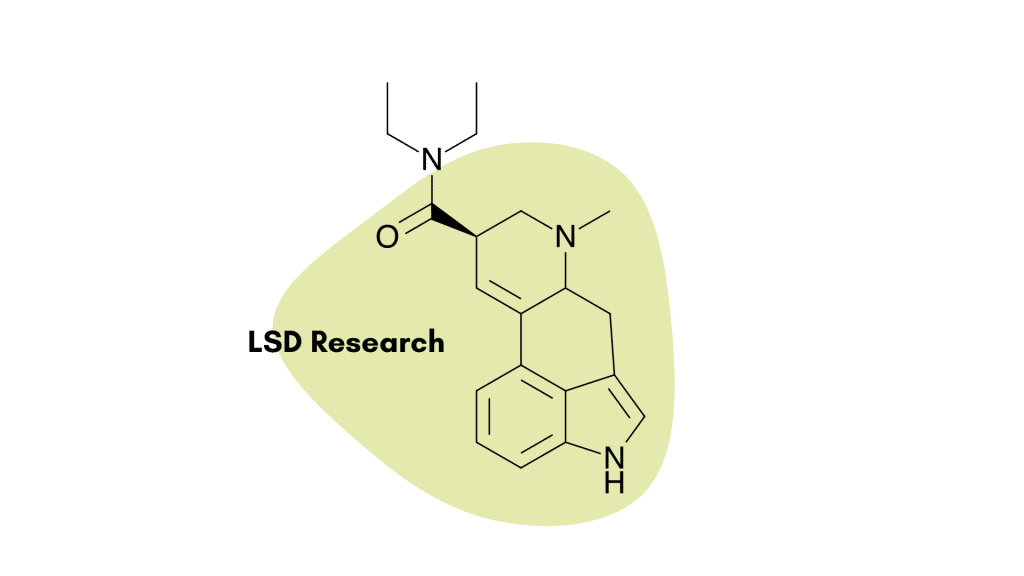

4. LSD Research

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) research began in the early 1960s with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert’s work at Harvard. This early research mainly involved giving LSD (and psilocybin) to graduate students, friends, and colleagues to essentially “see what happens.” The probity of this research wasn’t great, and aside from the Good Friday Experiment and the Concord Prison Experiment didn’t yield much value for the greater scientific community. However, it did lead Leary to develop the concept of “set and setting” — which remains a core aspect of psychedelic usage today.

Around the same time, the US government had a secret program called MK-ULTRA — during which the CIA attempted to use LSD as a mind-control agent or truth serum (it didn’t work). This program was not only a massive failure but a shocking display of pseudoscience and unethical test procedures.

Research came to a halt for several decades until, in 2014, MAPS conducted a phase II clinical study examining the effects of LSD on patients with illness-related anxiety (existential anxiety).

Since 2014, dozens of clinical trials have been published exploring the therapeutic potential of this intriguing molecule (and other members of the lysergamide family of psychedelics).

The study focus in recent years has been on treating existential anxiety, PTSD (and other trauma-related illness), cluster headaches, and as a tool for studying consciousness and brain networks. Within the past two years, some interesting research has started to surface, suggesting that LSD may even be useful for managing chronic pain.

Most of the funding for LSD research comes from philanthropy and government grants. The biotech company Eulesis did some work on LSD from 2016 to 2019 but has since pivoted towards their new drug “ELE-Psilo,” which is an intravenous form of psilocin.

This is a common problem with classical psychedelics like LSD and mescaline, which cannot be patented. Companies don’t want to invest their time and money into products they can’t patent. As a result, most of the research is focused on distinct preparations of ketamine, psilocybin, or novel psychedelic inventions instead.

LSD Research Summary:

- Areas of Research Focus: Existential anxiety, consciousness research, cluster headaches, pain

- Major Sponsors to LSD Research: Eleusis Therapeutics, MAPS, University Hospital (Basel, Switzerland)

- Lysergamide Pipeline:

Prominent Research on LSD & Lysergamides:

5. Ketamine Research

Ketamine was invented in 1962 by a scientist by the name of Calvin Stevens. It quickly gained interest as an alternative to PCP (phencyclidine) for use as an anesthetic during surgery. PCP was unreliable and sometimes led patients to experience bouts of psychosis lasting several hours after surgery.

Ketamine offered similar dissociative and anesthetic effects as PCP but lacked most of the major safety concerns associated with this powerful arylcyclohexylamine psychedelic.

One of the earliest applications of ketamine in psychedelic research was in the late 60s and early 70s. A researcher by the name of Salvador Roquet was studying the effects of various psychedelic compounds by administering patients with the drug and then exposing them to what he called “sensory overload,” — which involved lights, sounds, and imagery of violent or sexual acts. At the end of each session, he’d administer ketamine to “soften the landing.” He found that ketamine greatly alleviated the anxiety generated during the session.

Unlike other psychedelics, ketamine remained legal within the medical system throughout the 80s and 90s. It was only moved to the Schedule III status in the late 1990s. This gave psychologists the opportunity to experiment with it over the years. A group of clinicians at Yale were the first to discover that ketamine produced a marked improvement in mood. This led to a series of clinical studies in the early 2000s that have snowballed dramatically since then. By 2022 there have been well over 350 clinical trials on ketamine, most of which are focused on its unique antidepressant action.

The best summary of ketamine’s use in psychiatry is a book called The Ketamine Papers by Phil Wolfson, M.D. Wolfson is most famous for his work with MAPS and their formal study on MDMA for existential anxiety.

Ketamine is now well-established as a treatment for depression. The effects of a single session can last several days or weeks, depending on the individual. Ketamine clinics are popping up all over the world to administer ketamine to depressed patients every couple of weeks.

Like other psychedelic drugs, the patents for ketamine expired decades ago, so most of the research today is spent exploring the most efficient delivery methods as companies scramble to secure new patents in the emerging market.

Ketamine Research Summary:

- Areas of Research Focus: Depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation, chronic pain

- Major Sponsors to Ketamine Research: MAPS, Entheon Biomedical Corp, Johnson & Johnson, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Seelos Therapeutics Inc, Bexson Biomedical

Prominent Research on Ketamine:

Psychedelic Research Programs

Today there are several top-level universities conducting research on psychedelic substances — most of which have only established their psychedelic research departments within the last 3 or 4 years.

Thanks to an influx of philanthropic and corporate funding, along with renewed public interest and reductions in legal hurdles — the field of psychedelic research is alive and well.

Here are some of the most prominent universities with dedicated psychedelic research teams.

1. John Hopkins University: Center For Psychedelic & Consciousness Research

Johns Hopkins (Baltimore, Maryland) set up the Center For Psychedelic & Consciousness Research in 2000 after receiving approval from the United States. This marked the first federal grant approval for psychedelic medicine in 5 decades ($4 million).

The first study from the program published in 2006 changed the game for psychedelic research moving forward. The study found that psilocybin, when administered in a professional setting, was both safe and offered enduring positive effects after a single dose. This study, and others like it, eventually led the FDA to award psilocybin the title of “breakthrough therapy” for treating severe depression.

Johns Hopkins remains a leader in the field of psychedelic research with well over 60 individual clinical trials on the topics of smoking cessation, consciousness, existential anxiety, depression, and much more.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Roland Griffiths, Ph.D.

- Established: 2000

- Focus: Psilocybin, Addiction, Consciousness, Depression, Existential Anxiety

- Major Sponsors: Anonymous Donor(s), Usona Institute

2. University of California Berkeley: Center For the Science of Psychedelics

UC Berkely Center For The Science of Psychedelics (BCSP) channels funding through UC Berkeley grant programs to study the psychological and biological effects of psychedelic compounds.

The executive committee features the author of How To Change Your Mind, Michael Pollan, as well as the prominent researchers Devid Presti, Michael Silver, Dacher Keltner, Tina Trujillo, and Andrea Gomez.

This program is relatively new and has only published a few clinical studies so far on the effects of psilocybin on the demoralization of AIDS survivors and the clinical pharmacology of MDA (neither of which have been published yet).

Sign up for the UC Berkely psychedelic newsletter, The Microdose to keep tabs on this project.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Michael Silver

- Established: 2020

- Focus: Psilocybin & Amphetamine Psychedelics

- Major Sponsors: Anonymous Donor(s)

3. Icahn School of Medicine: Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai recently launched the Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research — a department dedicated to researching the therapeutic role of psychedelics in managing PTSD and other forms of trauma.

For the next few years, the center will focus on the use of MDMA and psilocybin for treating trauma-related illnesses but has plans to extend this to other psychedelics in the future as well. The Icahn School of Medicine plans to use neuroimaging, blood sampling, molecular biology, clinical trials, computational genetics, and more to perform various studies on psychedelic compounds.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Rachel Yehuda, Ph.D.

- Established: 2021

- Focus: MDMA, PTSD, Psilocybin

- Major Sponsors: The Bob & Renee Parsons Foundation, NIMH

4. University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland (Liechti Lab)

The University Hospital of Basel — Universitätsspital Basel (USB) in German — has been a leader in the psychedelic research space for several decades. It was one of the first places to start exploring the effects of LSD after it was invented in a separate Basel laboratory over 60 years ago.

In particular, the Liechti Lab (run by Dr. Matthias Liechti) is dedicated to the pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of MDMA, LSD, and amphetamines in humans. The lab recently partnered with the publicly traded company, MindMed to conduct 8 new clinical trials involving LSD.

The USB institution is very large, encompassing over 50 clinics and nearly 8000 staff members. It’s the largest healthcare facility in North-Western Switzerland.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Dr. Matthias Liechti

- Established: 2020

- Focus: LSD, MDMA, Methylphenidate

- Major Sponsors: MindMed

5. Massachusetts General Hospital: Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics

Massachusetts General Hospital established the Center For the Neuroscience of Psychedelics in 2020. The team has an ambitious goal to “make the term treatment resistant obsolete.”

The group is focused on understanding the role of psychedelics in neuroplasticity and facilitating change in neural networks. Research here is primarily focused on the use of MDMA and psilocybin at the moment, but the group plans to extend this to other psychedelic compounds in the future.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Jerrold Rosenbaum, MD

- Established: 2020

- Focus: MDMA, psilocybin, PTSD, treatment-resistant depression

- Major Sponsors: Atai Life Sciences

6. University of Wisconsin: Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances

The Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances was first established in late 2020. The team’s focus is centered around “the science, history, and cultural impact of psychedelic agents, in addition to studying the potential for therapeutic use of psychoactive substances.”

The group isn’t doing clinical studies at the moment but plans to roll out clinical trials in the future through its on-campus clinical centers.

So far, the program has conducted clinical trials exploring the efficacy of MDMA in treating PTSD, psilocybin for managing clinical depression, and psilocybin for treating addiction to opioids.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Paul Hutson

- Established: 2020

- Focus: MDMA, Psilocybin, PTSD, Depression, Addiction

- Major Sponsors: Unknown

7. NYU Langone’s School of Medicine: Center for Psychedelic Medicine

The Center For Psychedelic Medicine at NYU was founded in 2020 after receiving $10 million in philanthropic funding. The goals of this research group are to “conduct and promote research across the translational spectrum in order to realize the clinical potential of these drugs, maximize their safety, unlock their mechanisms of action, and determine which patients are most likely to benefit from psychedelic treatments.”

The center is currently working on studies involving the use of psilocybin for treating alcohol use disorder, psilocybin for major depressive disorder, and MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Program Specs:

- Program Director: Michael Bogenschutz, MD

- Established: 2020

- Focus: MDMA, Psilocybin, Depression, PTSD, Alcohol Abuse Disorder

- Major Sponsors: MAPS & The Hefter Institute

Who Pays For Psychedelic Research?

Clinical research is outrageously expensive and slow-moving. The average cost for a clinical trial is around $4 million for a phase I trial, $13 million for phase II, and $20 million for phase III. The FDA will only approve substances that have passed phase III. The cost for this research costs an average of $40 K per participant.

So who pays for all this research? And what do those who support psychedelic research stand to gain from this hefty investment?

There are four main types of groups that are currently funding psychedelic research — each one with different motivations behind them:

1. Government Programs

The National Institutes of Health recently approved funding for psychedelic research at Johns Hopkins University. This marks the first time the US government has funded psychedelic research in more than 5 decades.

Prior to this, the last government-funded program was the infamous MK-ULTRA Project, in which the CIA administered LSD and other psychoactive substances to people from all walks of life. They were hoping to use these substances as a truth serum or mind-control agent (to no avail).

Just north of the border, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) recently approved a grant for $3 million to fund research on psilocybin (final approval will be made in winter 2023).

It makes sense for governments to fund psychedelic research for its potential role in the mental health of society at large. Clinical studies already support the idea that certain psychedelic plants and fungi can help reduce the epidemic of addiction, depression, anxiety, and PTSD prevalent among the global population. Every dollar spent on improving the mental health of the populace pays dividends for the society in the form of increased productivity, reduction of crimes of desperation, and reduced burden on the public health system.

2. Non-Profit Organizations

Most of the progress on psychedelic research in recent years comes from the work of non-profit organizations like MAPS, the Hefter Institute, the Beckley Foundation, the Usona Institute, and others.

Today, psychedelic research is trendy, and there are a lot of companies investing with the hopes of making money from the industry in the coming years. It only reached this point because of some critical investment from philanthropic donors and the hard work of NGOs lobbying governments, organizing clinical trials, and providing free public education.

Here are some of the most prominent Medical Research Organizations (MROs) supporting psychedelic research:

MAPS

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is a non-profit organization in San Jose, California. The organization was formed in 1986 by Rick Doblin, Ph.D. — who was a young researcher at the time exploring the therapeutic role of MDMA in psychiatry. The DEA had just recently moved to ban MDMA, so Doblin and a few of his colleagues set up MAPS to continue this important research.

MAPS has raised well over $130 million to fund psychedelic research and education and is the leading sponsor for MDMA research in the world.

After 35 years of hard work and research, MAPS is finally on the brink of bringing MDMA therapy back into the hands of clinicians. This time with a powerful protocol for using this important medicine in the treatment of PTSD, depression, and more.

Program Specs:

- Executive Director: Rick Doblin

- Established: 1986

- Focus: MDMA, PTSD, Depression, Psilocybin

The Heffter Institute

The Hefter Institute is a non-profit started in 1993 by David Nichols, Dennis McKenna, and Mark Geyer — all of which are considered leading figures in the psychedelic academia.

The group channels funding from philanthropists and organizations to fuel psychedelic research and has contributed to over 60% of the top-cited articles in psychedelics today.

The Hefter Institute was named in honor of Dr. Arthur Hefter — a German pharmacologist who conducted the first official studies on hallucinogenic substances in the late 1800s.

The board of directors consists of leading psychedelic researchers and philanthropic donors such as Carey Turnbull, Roiland Griffiths, Charles Grob, George Greer, Janis Phelps, T. Cody Swift, Claudia Turnbull, and Franz Vollenweider.

The Hefter Institute funds and organizes all kinds of psychedelic research but has been particularly focused on research involving psilocybin in recent years. The group has run clinical studies examining the effects of magic mushrooms (and other compounds) on treating existential anxiety, cancer, depression, and addiction. They’ve also funded research examining the connection between psychedelics and spirituality and mystical states of consciousness, as well as neuroscience and pharmacology research.

Program Specs:

- Executive Director: Carey Turnbull

- Established: 1993

- Focus: Psilocybin, existential anxiety, depression, addiction

The Usona Institute

The Usona Institute is a non-profit research fund dedicated to what the group calls “open science.” The team is dedicated to providing research for the public good, advancement of scientific knowledge, and alleviation of mental suffering.

Usona works with various research groups around the country to provide funding and guidance for clinical studies on psychedelics. They’ve worked with Johns Hopkins, CIIS, Yale, the University of Zurich, Imperial College London, and many other top-level research institutions.

The institute is working to funnel money towards research on psilocybin and discovering and cataloging new psychoactive substances.

The Usona Institute was founded in 2014 by Bill Linton and Malynn Utzinger, M.D.

Program Specs:

- Executive Director: Bill Linton

- Established: 2014

- Focus: Psilocybin, synthetic cathinones, 5-MeO-DMT, new psychedelic molecules

The Beckley Foundation

The Beckley Foundation is an NGO and think tank based out of the UK dedicated to scientific discovery and policy reform around psychedelics. The founder, Amanda Feilding, has been working with researchers in the psychedelic space for a long time and has since been dubbed the “Queen of Consciousness” for her contributions.

The Beckley Foundation has funded research on a wide range of psychoactive compounds, including MDMA, cannabis, LSD, psilocybin, ayahuasca, and 5-MeO-DMT. They’ve been directly involved in over 80 publications in cooperation with an impressive array of institutions and clinics around the world.

Research topics include LSD for creativity, ceremonial uses of ayahuasca, microdosing LSD for mood, microdosing LSD for pain, the effects of psilocybin on personality structures, and much more.

Program Specs:

- Executive Director: Amanda Feilding

- Established: 1998

- Focus: LSD, Psilocybin, Ayahuasca, MDMA

3. Corporations & Venture Capital Firms

Today, there are more than 50 publicly traded companies involved in the development of psychedelic drugs in the US alone. So far, just three are valued at over $500 million in market cap — Atai Life Sciences ($850 million), Compass Pathways ($500 million), and MindMed ($450 million).

Companies operating in this space fund research to develop new drugs, new delivery methods, and clinical protocols using psychedelics in anticipation of an upcoming boom in the psychedelic mental healthcare space. The market is expected to reach $10.75 billion by 2027.

Other public or private companies funding psychedelic research include:

- Aja Ventures

- Albert Labs

- Cybin

- Eleusis

- Field Trip Health

- Fluence

- Havn Life

- Ixtlan Bioscience

- Numinus Wellness

- Orthogonal Thinker

- Psyched Wellness

- Seelos Therapeutics

4. Private Philanthropy

Every year, an increasing number of people donate their own money to help fund psychedelic research.

In 2019, $17 million was donated by the private foundation of just four philanthropists (one of which included Tim Ferriss) and led to the creation of the Center For Psychedelic Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins.

Others have followed suit at all levels of donation — from $1000 up to tens of millions.

Some philanthropists donate through their corporate entities. A few notable examples include Dr. Bronners, MUD/WTR, and Ben & Jerry’s.

Some of the biggest philanthropic donors include:

- Steven & Alexandra Cohen (Point72 Asset Management) — $18.9 million

- Genevieve Jurvetson (Fetcher) — $2.6 million

- Bob Parsons (GoDaddy) — $2 million

- Tim Ferriss — $2+ million

- Cody Swift and Miriam Volat (RiverStyx Foundation) — $1.67 million

- Joby Pritzker (Private Equity) — $1 million

- Alan Fournier (Pennant Investors) — $1 million

- John Griffin (Blue Ridge Capital) — $1 million

- George Sarlo (Walden Venture Capital) — $1 million

- James Bailey (Bail Capital) — $1 million

- Blake Mycoskie (TOMS Shoes) — $1 million

- Peter Rahal (RxBar) — $1 million

5. Anybody Can Donate to Psychedelic Research

If you’re interested in donating to future psychedelic research on a one-time or ongoing monthly basis, consider signing up with one of the foundations listed below. Any denomination is accepted.

- → Donate to MAPS

- → Donate to the Usona Institute

- → Donate to the Hefter Institute

- → Donate to the Beckley Foundation

What’s The Future of Psychedelic Research?

Based on the trajectory of psychedelic research, we’re very likely to see some significant changes in policy surrounding these substances over the coming years.

Maintaining substances in the top-tier of restricted substances (a title that claims zero medical viability and high risk for abuse) is becoming more contradictory every year as new studies clearly demonstrate the powerful medicinal attributes of substances like MDMA, psilocybin, and LSD.

As laws become more relaxed and psychiatrists are able to integrate these substances into their practice, the research is only going to improve. More patients, more data, and more skilled practitioners contributing to the field are only going to further enrich our understanding of what it means to be conscious, happy, and healthy.

Organizations currently studying psychedelics will likely continue to expand — eventually offering graduate programs for people interested in advancing our understanding of the human brain and mental health through the study of psychedelics and altered states of consciousness.

We’re currently sitting at the base of a major renaissance in psychedelic research that’s starting to move the needle on treating some of the most challenging conditions present in society — addiction, depression, acknowledgment of our own death, and trauma-related illness.