Problematic Data Collection Policies Threaten Patients in Oregon

When Oregan’s Measure 109 contained language protecting the data and rights of patients seeking out the newly legal therapy. Now, it all could crumble.

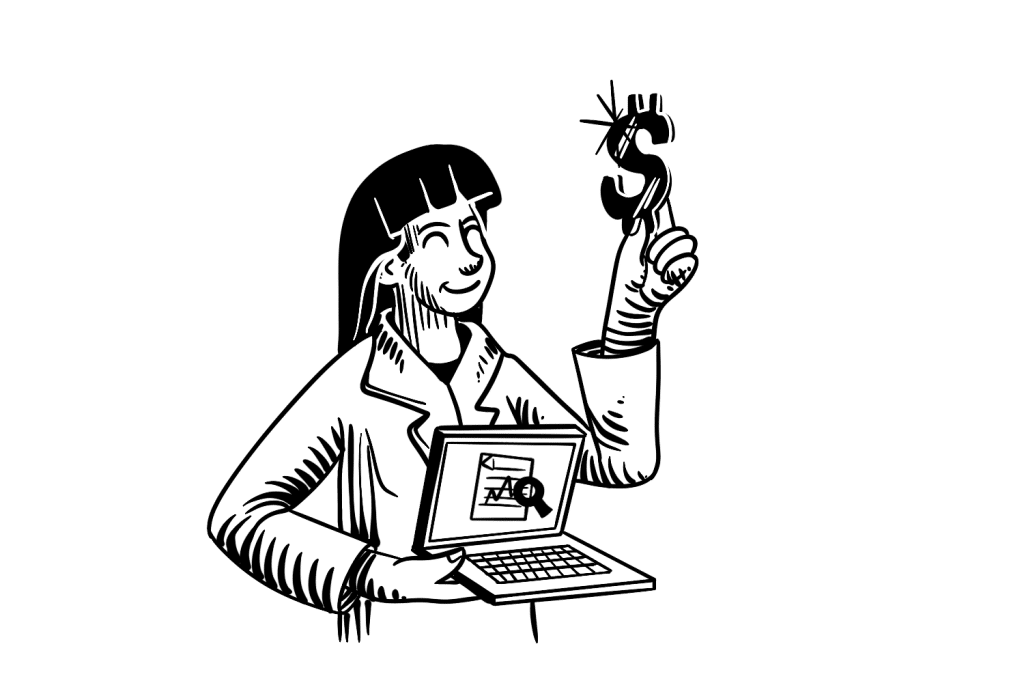

As some begin to celebrate the recent release of psilocybin therapy to the citizens in Oregon, there are already risks at play. Senator Elizabeth Steiner introduced Senate Bill (SB) 303 shortly after the finalization of rules for psilocybin therapy in Oregon.

Negotiating and finalizing these rules took two years to complete, and one of the most hotly contested debates was over data rights. Public outcry was the only reason the advisory board reversed their previous decision to require the collection of data and gave clients the right to opt out.

Should this bill pass, it will mandate practitioners to share large volumes of data with the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) and the Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU). Several concerns arise from this potential requirement.

Related: The State of Psychedelic Drug Laws in Oregon

How SB 303 Undermines the Rights in Measure 109

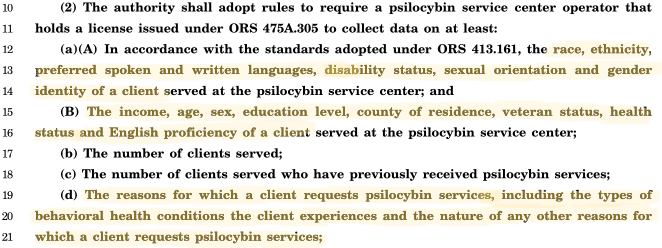

The goal of SB 303 is to force psilocybin practitioners “to collect and report data regarding psilocybin services.” As many others are pointing out, the amount of information they would like to receive far exceeds the amount they could receive from other medical treatments.

Skirting the criminalization of psilocybin and its prior status in research, Oregon distinguished psilocybin therapy from medical interventions. Clients — not “patients” — must seek treatment without a prescription in facilities that cannot offer medical treatments or diagnoses.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rights — the legal requirement of absolute confidentiality for medical interventions and conditions — do not apply. People began speaking out about this fact early on and, through a contorted fight, won.

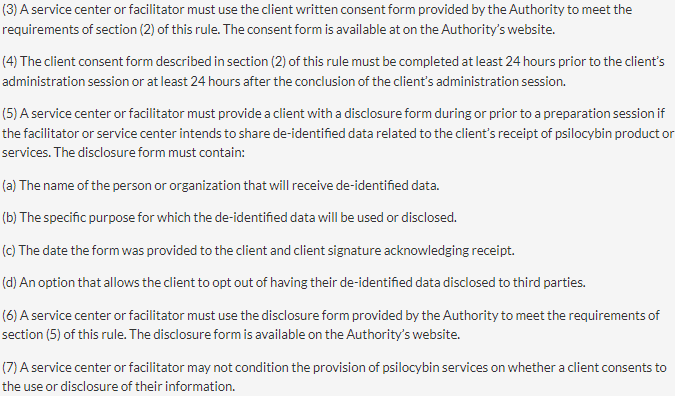

There are several protections for clients in the final rules for measure 109., including the right to opt-out and the prohibition of facilitators from requiring participation to receive service.

SB 303 would reverse these, compelling practitioners to report sensitive data to third parties. While this information may be “de-identifiable,” it creates a government repository of everyone attending these legally questionable activities with the following information:

Access to — “at least” — demographic information, medical conditions, income level, sexual orientation, and geographical location is a lot to go off. Public opinion may be favorable on psychedelics now, but there are no protections for these clients should the political landscape shift.

Members of the free love movement likely thought things were changing for good in 1968 before Nixon won the election and brought with him the rise of modern American conservatism. Public opinion changes and people are less likely to seek treatment if their information is stored.

Practitioners likely share this fear of detailing elements of their federally illegal activities. The above includes the number of clients they serve, but continues:

What is the Point of SB 303?

The main argument for proponents of SB 302 revolves around collecting data to study effectiveness. Indeed, the information from these sessions could immensely help researchers understand the impact of psychedelics — but that doesn’t give the government a right to mandate them.

Psilocybin therapy couldn’t pass as a medical treatment, so the outcomes of individuals should be of no importance. Aggregated statistics might make sense, but requiring clients to report the symptoms they’re seeking treatment for while simultaneously refusing to accept them as a treatment for those symptoms is a bit much.

Participants should be able to — and currently can — provide their data to a third party if they wish. Being on the scientific forefront is exciting for a lot of people who aren’t worried about their psilocybin use being a public matter.

Some have even suggested that practitioners could offer financial incentives for participating in these surveys or charge more for anonymity. In all cases, the person seeking treatment has a choice.

SB 303 removes autonomy and puts participants into a massive medical trial against their will.

How is SB 303 Possible?

Mason Marks, a law professor at Florida State University, received a series of emails in November 2022 from a public records request. In detailing his findings in his newsletter, Marks found a “close collaboration between the state agency, lobbyists from the Healing Advocacy Fund, and members of the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board.”

He also discovered a secretive program at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) called the Oregon Psilocybin Evaluation Nexus, or (OPEN), project. The program sought to collect data on psilocybin clients and allegedly involved some advisory board members in pivotal roles.

Throughout the correspondence, Marks found OHA showed preferential treatment to lobbyists, eventually letting them sway their opinion on data collection. Public outcry finally forced them into reversing their opinion on this, however.

So it was that, after two years and millions of dollars, they released their final rules without forcing data collection.

This bill requires practitioners to collect the data and hand it over to OHSU — the same University with questionable ties to the OHA that lobbyists were pushing for. Also the same University, for what it’s worth, Senator Steiner worked as an adjunct professor.

SB 303 seeks to amend the sections that the citizens of Oregon fought hard to obtain. It goes directly against the will of the people who spoke out loudly against data collection — when it was appropriate to do so.

Decriminalization Cannot Exist Without Confidentiality

The motivation for decriminalization is to bring underground services into the light and offer protections to those who seek them out. For someone operating in a gray area like psilocybin therapy, confidentiality is crucial to establishing trust.

Drug users have had to look over their shoulders when using illegal substances for decades. If they must be put on a list or stored in a database to seek it out legally, far fewer will do so.

As long as psilocybin is still federally illegal, it is unsafe to openly consume and provide it. SB 303 disregards participants’ autonomy in a pioneering program while discouraging practitioners from operating legally.

For owners of psilocybin clinics, SB 303 increases the burden of operation and forces them to disclose more than Measure 109 initially asked for. You can’t reasonably expect a practitioner who has operated underground for years to reveal the exact quantities of federally illegal drugs they have given out every day.

Removing confidentiality while decriminalizing the action emboldens clandestine operations. Having medical-grade oversight on services that aren’t medically recognized makes people less likely to move above ground.

Beyond the discouragement, there’s the fear of having the government perform research experiments on vulnerable populations against their will. If Oregon wants decriminalization to discourage illegal activities, it must ensure the legal ones are appealing enough to transition.

What’s the Future Look Like for Psychedelics in Oregon?

It is still unclear when SB 303 will receive its first vote, but the Senate Committee on Healthcare is next to listen to it. Through Measure 110, Oregon doesn’t currently criminalize personal possession or use of any drugs, so psychedelics are already effectively legal for personal use.

Unfortunately, this may see a battle of its own soon. House Bill (HB) 2831 — which seeks to repeal Measure 110 — was similarly sent to the House Committee on Behavioral Health and Health Care shortly after SB 303.

If both are successful, Oregon will effectively restrict all psilocybin use in facilities and require them to collect and report data on participants.

Both measures are currently in flux, waiting for their committees to assign them. As a result, the momentum Oregon has gained in fighting the war on drugs is in limbo.