THCA vs THC: Key Differences & Similarities Explained

THCA is the predominant cannabinoid in marijuana, so how are states without restrictive cannabis laws still selling it?

As a cannabis plant begins to mature, a series of complex molecular interactions begin forming and altering compounds into molecules. These will eventually produce all cannabinoids, terpenes, and other components of the plant.

When the flowers begin to form, cannabinoids gather in the sticky white hairs (trichomes), mainly stopping as tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) or cannabidiolic acid (CBDA). Even within products sold as THC and CBD flower, these are the true form they are typically in.

Smokable flower converts the THCA into delta-9 THC slowly over time or rapidly during consumption through the process of decarboxylation.

Here’s a quick rundown of everything we’ll cover in this guide:

While the two cannabinoids are often interchangeable, understanding their key differences is crucial for any avid cannabis consumer.

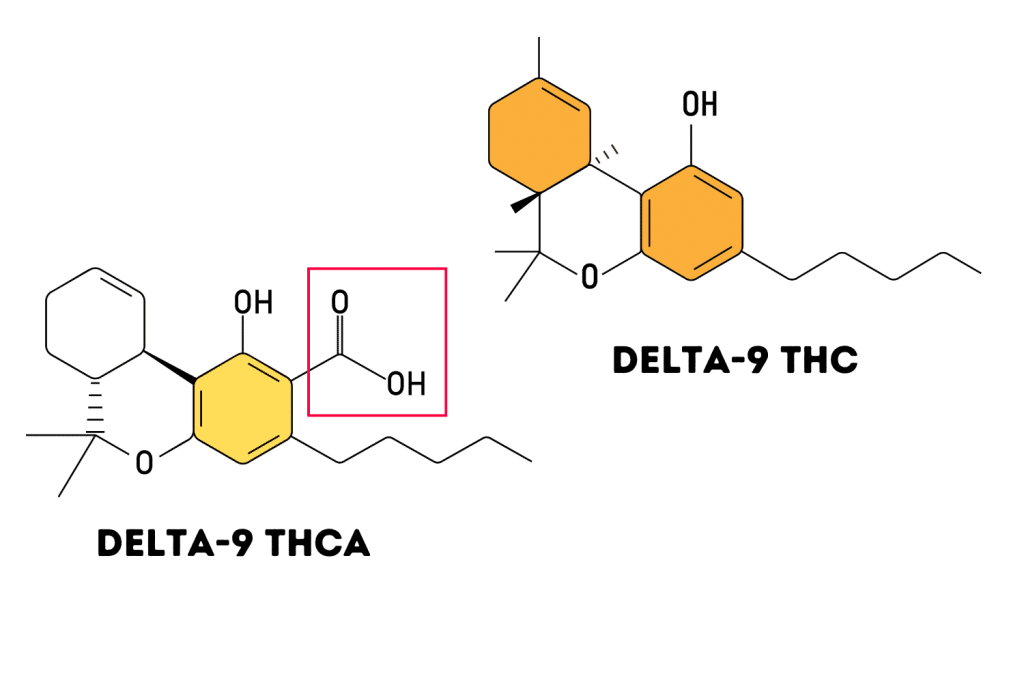

Molecular Differences Between THCA & THC

THCA is nearly identical to THC on a molecular level, with the only difference being a minor grouping of atoms. This addition makes THCA acidic and hinders its ability to interact with the same receptors as THC [1].

The “carboxyl ring” in THCA contains a carbon (C) atom near the middle bonded to a “hydroxyl group” — oxygen and hydrogen bonded together (OH) — with a double bond to another oxygen (O) atom. Collectively, this is the COOH group, and it is the only difference between the two.

For this reason, literature sometimes refers to THCA as THC-COOH, and it’s not uncommon for plants and fungi to do this. Amanita muscaria mushroom produces ibotenic acid instead, which requires decarboxylation to become the active muscimol [2].

In both cases, the more resilient molecule forms to protect a less resistant active compound. Unlike a pharmaceutical approach, plants have to produce their compounds through a “biosynthetic” process of complex interactions to build the cannabinoids and other compounds up from scratch.

In cannabis, the “mother of all cannabinoids” is cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), which, itself, is the product of various reactions within the young cannabis plant coming together.

Through various interactions, CBG can become the acidic form of the three main cannabinoids — CBD, THC, and cannabichromene (CBC). All of these have gone severely under-researched due to an initial dismissal of “inactivity” since they don’t cause any level of intoxication.

Though limited, THCA may actually help treat some of the same things THC is commonly used for without a “high.”

THCA vs. THC: Interactions With The Brain & Body

Studies differ on THCA’s effect on the main receptors THC interacts with — CB1 and CB2 in the endocannabinoid system (ECS). THC has a high affinity for CB1 receptors, which are primarily in the central nervous system (CNS) but also scattered throughout the brain and body.

THCA likely does as well, in a different way [3]. Though reliable studies are scarce, at least two indicate THCA could bond with the CB1 receptors nearly as well.

This makes it seem like THCA could activate receptors in the same way as THC but without access to the bulk majority of them in the CNS. As a result, THCA is unable to cause feelings of intoxication and can influence the ECS in subtle, unique ways.

Additionally, THCA has protective qualities over the immune and neurological systems and may help reduce inflammation to combat pain. How it does so is still a mystery, but it seems likely the endocannabinoid system only plays a minor role in them.

Researchers have uncovered that THCA has an antagonistic effect on the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. These are responsible for detecting cold temperatures [4], so they may also play a role in inflammation and pain.

Whether THCA offers similar benefits to THC through the same mechanisms or ones unique to it is something researchers will have to recover. What we know now, however, is that THCA shows promise and works in both identical and differing ways.

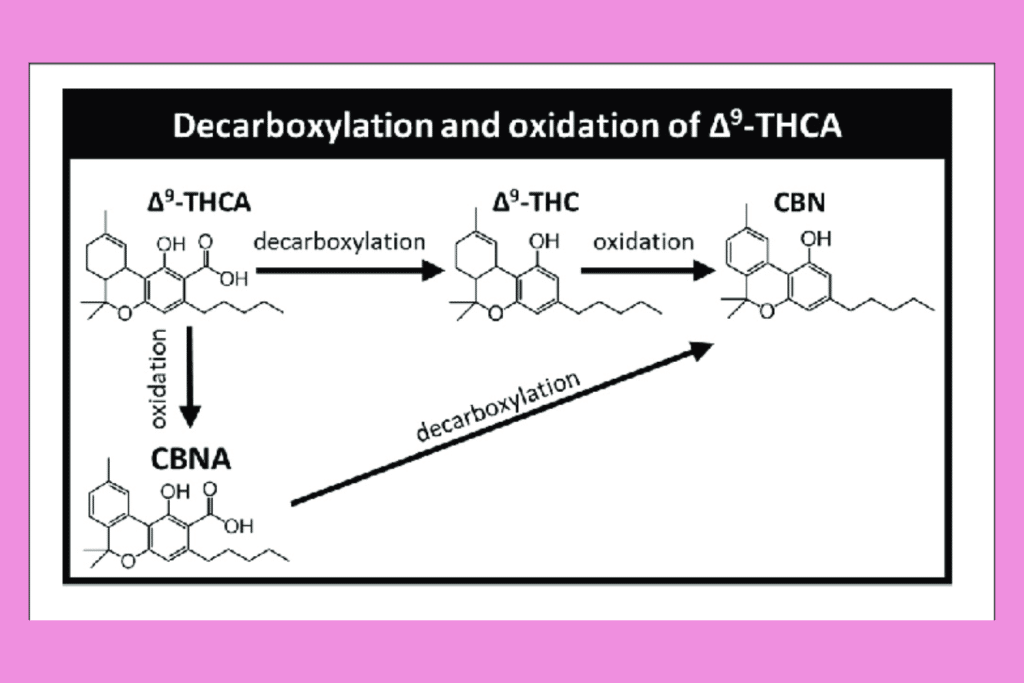

How THCA Turns Into THC (Decarboxylation)

THCA is a more stable molecule than THC, requiring a bit more energy for it to decarboxylate. By contrast, THC degrades rather easily through oxygen and time alone into cannabinol (CBN) — and it can even do so when smoking [5].

CBN may offer benefits of its own, but it’s non-intoxicating and is typically not the goal of anyone decarboxylating THCA. For consumers smoking joints or big bowls over a long period, this may happen in larger quantities.

While the ideal environment can reportedly convert THCA to THC at 87.7% of the original rate, it’s unlikely this would ever be possible at home. Depending on the consumption method, expect closer to a 30–70% conversion rate.

In the presence of heat — like the flame of a lighter or the high heat of a vaporizer — THCA loses the carboxyl group (decarboxylates) to become THC. The carbon and two oxygen molecules from the COOH group are released as CO2 and leave behind hydrogen, forming delta-9 THC.

While decarboxylation is common in nature, the simplistic nature of the process in cannabis is not [2]. Most other natural forms of decarboxylation use other enzymes to create more complex conversions or even form entirely new molecules.

While this is a remarkable component of cannabis, it also points out how unstable THCA can be. If it readily degrades from ambient light and air, it takes delicate storage, drying, and processing techniques to prevent it from doing so.

Furthermore, the federally legal THCA flower you buy online could very well become an illegal product before or after reaching your hands.

It can take months from when a crop is first sent off for testing until it’s on the shelves for consumers. After purchasing, it might sit in a jar in your room for another couple of months before it’s gone.

THCA vs. THC: Metabolism

After consuming anything, your body will break it down through the metabolic process into “metabolites.” The first step of breaking down THC and THCA is to metabolize it into 11-hydroxyl THC/THCA [3].

The former is an active metabolite responsible for the extended duration of effect with edible cannabis products. The latter is nearly identical, but the carboxyl group remaining on the molecule still restricts it from accessing the CNS.

If you’ve ever made edibles on your own, decarboxylation is always listed as the necessary first step. This process happens regardless of the way a person chooses to consume THCA or THC, though the ease of decarboxylation makes THCA impossible to smoke or vape.

In time, both metabolites turn into 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC and THCA, releasing through the urine and feces over time. These are the targets of urinary tests and can remain in the system for anywhere from 3 to 30+ days, depending on several factors.

Depending on the sensitivity of the testing you undergo, it may or may not be able to tell the difference between the 11-nor versions of THC and THCA.

Health Benefits

Researchers initially discredited THCA as an inactive precursor to THC since it didn’t make users feel high. However, studies are starting to indicate it has several benefits of its own.

Here’s a breakdown of some of the ways THCA could help:

| Benefit | Mechanism of Action |

| Inflammation & Pain Relief | In addition to its interaction with the CB1/CB2 receptors, THCA is an agonist for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [6], which has a direct role in inflammation response (among other things) [7] |

| Weight Management | PPARγ also influences metabolism and can help control weight gain, lower body fat, and may even help with diabetes management and other diet-related metabolic conditions [8] |

| Neuroprotection | The anti-inflammatory properties of PPARγ agonism translate into combatting neuro-inflammation and diseases stemming from it like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s Disease [6] |

| Immunological Regulation | THCA was able to reduce tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a powerful component of immune response [9] |

| Antiemetic (Nausea & Vomiting Prevention) | Also a major use for THC, THCA may offer a similar amount of antiemetic benefit without the mind-altering effects, making it useful for those sensitive to the “high” feeling [10] |

| Anti-Tumor/Anti-Cancer | Some studies show THCA can help to inhibit the spread and survival of breast cancer and potentially other forms of cancer [11] |

It’s important to note that all of the studies above are introductory and involve small sample sizes — often of rodents and not humans. THCA research is still in its infancy and there’s a lot of possibility for more exciting (or disappointing) findings.

THCA’s unique action on similar and different systems from THC may open a new door for cannabis treatments. If nothing else, one thing is certain: THCA is not “inactive.”

Health Benefits of Marijuana

Knowledge of the medicinal value of smoking marijuana dates back nearly 3,000 years to the traditional Indian practice of “Ayurveda [12].” Many of the benefits of cannabis researchers have been “discovering” in the last century and a half or so were common knowledge to groups of people 3+ millennia ago.

Some of the common reasons for using cannabis include:

- Pain relief

- Antiemia and anti-convulsant

- Appetite stimulation

- Aphrodesia

Additional historical uses included:

- Topical applications for inflammation and infections

- Bronchitis and asthma as an “expectorant” (helps cough up phlegm and mucus)

- Diarrhea and gastrointestinal problems

While this was the first written account, India likely learned of this practice from people in surrounding countries where there is evidence of its use predating Ayurvedic medicine. We can’t say for sure how long ago people have been using cannabis, but it seems likely the discovery happened somewhere in modern-day Iran.

Another element of THC that we shouldn’t dismiss is the euphoric state it can bring in consumers. This has made it a tool of mental health, spiritual practice, ritual, and community-building for generations upon generations.

Is The High Of THC Helpful?

Many of these ancient sources refer to the intoxication of cannabis as the point rather than a byproduct. Some traditions may have even associated cannabis and the high it provides directly with a spiritual experience, offering it as a sacrifice through burning — if they huddled around, this would be like an ancient clan bake.

Not everyone enjoys getting high, and it’s common for people to be sensitive or just not like THC, but it can make a major difference for some. Outside of just making you giggly or happy, this shift in mindset can make healing and quality of life far easier and more enjoyable.

Recent studies have found that medical cannabis use improved energy and vitality in 68% of 100 participants [13]. 88% reported they were better able to perform their professional duties, and 79% said they were able to sleep better.

These markers are healing in their own right, whether cannabis helps outside of them or not. For the 96% of participants who reported a decrease in their symptoms, we can’t determine whether it came from a pharmacological benefit or better mood, work performance, and sleep habits, improving their general quality of life.

There’s nothing wrong with using THC recreationally, philosophically, or for self-exploration — remember, THC can be “psychedelic” as well [14]. If you treat it with the same level of respect you would a magic mushroom trip; you’ll get far more out of it than mindlessly puffing away on a vape pen or endlessly rolling joints.

Is THC or THCA Stronger?

Technically speaking, there’s virtually no difference between THC and THCA flower outside of minor changes to drying and curing processes. In legal markets, regulations typically require producers to add the normally small amount of delta-9 THC to 87% of THCA — accounting for the added weight of the carboxyl ring THCA will shed.

This means the “Total THC” percentage on the label comes from this formula:

Amount of THC + (.877 * Amount of THCA) = Total THC

With THCA flower, the labels reflect 100% of the THCA, and there is rarely any THC to add on. If the same product were sold in states where marijuana is legal, a 30% THCA flower would have a label of 26% THC.

One study suggested only 75% of the THCA converts to THC, with some of that degrading into CBN. Their suggested formula for a realistic understanding of THC content would be:

Amount of THC + (.75 * .877 * Amount of THCA = Actual THC

This means a strain with 32% THC on the label (assuming THCA to make up 30%) would have an actual THC potential of:

2% THC + (.75 * .877 * 30% THCA) = 21.7%

It’s also important to remember that THC is surrounded by terpenes, minor cannabinoids, and other compounds bolstering and altering its efficacy, however.

Since THCA flower goes through a more strict growth, curing, and packaging process to prevent THCA from decarboxylating, it may help with the “supporting actors” as well — perhaps offering a more rounded experience.

How Terpenes Affect THCA & THC Flower

The term “entourage effect” began as a hypothetical explanation for the varying effects of cannabis-based on factors outside of THC content. THC alone should impact the same person in similar ways every time — yet anyone familiar with cannabis will tell you that some strains can lock them to the couch and others make them clean uncontrollably.

We refer to these broadly as the classification of “Indica” or ”Sativa” (indica, as the story goes, “puts you in-da-couch”). However, most people who have looked into it will tell you these are mostly made-up categories and may or may not represent one of many different elements of the cannabis effect.

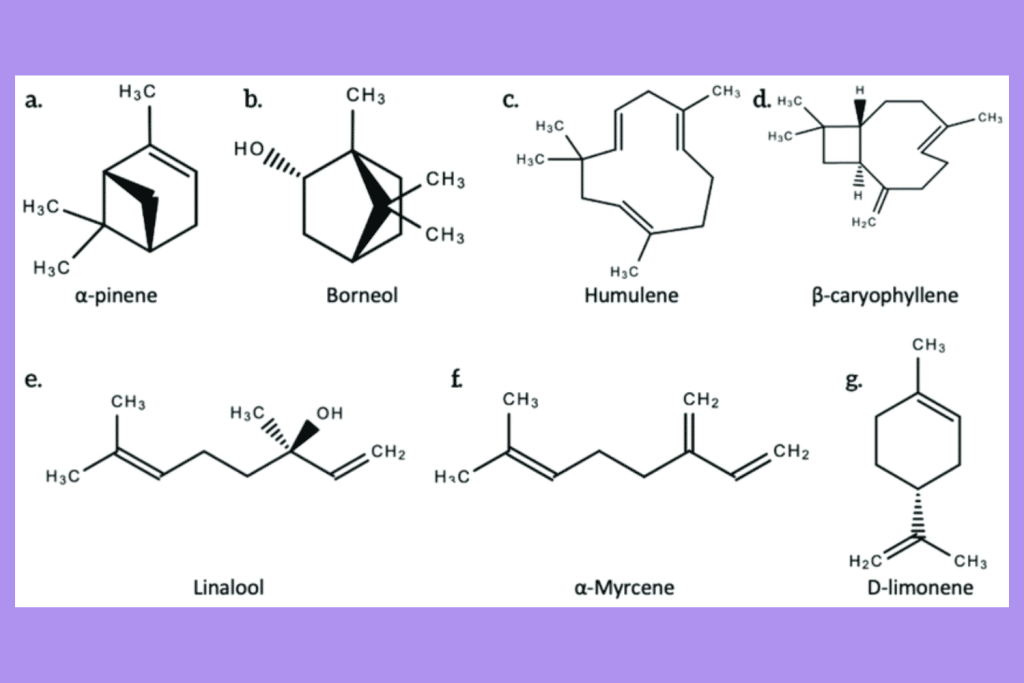

Most of the variations in cannabis experiences can come down to the wide range of terpenes — aromatic essential oils — found within the flower. While these occur widely throughout the natural world, cannabis is a powerhouse for eclectic terpenes with real benefits.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the main terpenes you’ll find in cannabis [15,16]:

Pinene

| Other Natural Sources | Aroma/Flavor | Boiling Point |

| Pine (Pinaceae) Tree Sap And Extracts | Like a walk through the woods, botanical flavor in the smoke | 155°C / 311°F |

Various preliminary studies have found pinene potentially offers anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and anti-viral benefits. Pinene can also boost the effect of THC, with at least one study reporting it has cannabis-like — or “cannabimimetic” — traits [17].

Pinene isn’t the only terpene to create cannabimemetic effects, but it’s certainly a favorite among enthusiasts. This terpene is commonly found in sativa and hybrid strains, as it’s rather versatile and with a low impact on mood or energy levels.

Myrcene

| Other Natural Sources | Aroma/Flavor | Boiling Point |

| Hops (Humulus lupulus), Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis), and Lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) [18]. | Slightly sweet aroma and flavor, common in strains with dessert-related names (often a form of cake, donuts, candy, or other sweets) | 168°C / 334°F |

At least two studies have found myrcene can help provide pain relief as an agonist for two different, yet related, targets. This also suggests it’s relaxing, which is why it’s often a dominant terpene for “Indica” strains.

A 2019 rodent study found myrcene outperformed all other terpenes in activating nociceptive transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channels (TRPV1) [19]. These mainly function by restricting or increasing the flow of calcium, and myrcene is capable of activating (agonist) them better than all other terpenes they tested.

Another rodent study from 1990 found that the opioid-receptor blocking naloxone negated the pain relief of myrcene [20]. This prompted researchers to question whether it stimulated the release of endogenous opioids (endorphins and/or enkephalins) through the common pathway of activating the alpha-2-adrenoceptor.

This is inconclusive at best, and some research shows alpha-2-adrenoceptors could inhibit TRPV1 receptors. While we don’t know how it works, myrcene seems to help with pain and relaxation in one way or another.

Caryophyllene

| Other Natural Sources | Aroma/Flavor | Boiling Point |

| Black Pepper (Piper nigrum), Hops, Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), and many others [21] | Peppery, diesel-like aroma with a spicy taste in the smoke, similar to black pepper or garlic | 263°C / 505°F |

Caryophyllene is remarkable in its capability to influence the endocannabinoid CB2 receptor, making it a terpene that also acts as a cannabinoid (terpenoid).

Some of the potential benefits of caryophyllene include:

- Pain relief

- Metabolism and metabolic diseases

- Anti-cancer treatment

- Liver-protection and healing

- Neuroprotection

- Anti-inflammation

Caryophyllene works through a shocking number of mechanisms to deliver a wide range of results. If you’ve ever heard of the home remedy of chewing a peppercorn to relieve headaches, caryophyllene may give the claim some credibility.

Caryophyllene’s boiling point is far higher than the rest of the components of cannabis, meaning it may not get through as well when it comes to vaping. However, it’s worth noting that the boiling points of all cannabis compounds are variable, and reports often conflict with each other.

Limonene

| Other Natural Sources | Aroma/Flavor | Boiling Point |

| Citric Fruits (Oranges, Lemons, Tangerines, and Grapefruit Juice 98%+ Limonene) [22] | Citric, lemony burst of aroma and flavor with a tart aftertaste | 176°C / 348°F |

The only terpene that truly earns a position in the “sativa” categories, limonene has shown tremendous promise with mood elevation and relieving anxiety. It also may act as an anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and analgesic compound by interacting with various receptors.

Of particular note is limonene’s ability to activate the serotonergic 5-HT1A and dopamine receptors [23]. If you’ve taken a hit of some bud and felt profound happiness and cerebral high, it was likely chock-full of limonene.

Limonene is also the main component of lemon essential oil and is the reason you might feel a bit happier when you put some in the diffuser as well. If you’re looking for an uplift in mood, try reaching for a limonene-dominant strain.

Linalool

| Other Natural Sources | Aroma/Flavor | Boiling Point |

| Lavendar (Lavandula angustifolia), Grapefruit (Citrus paradise), Bergamot (Citrus bergamia), Thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and Juniper (Juniperus communis) [24] | Slightly citric, sweet aroma with a tasty flavor — also very common in dessert strains and “grape” or “soda” strains | 198°C / 388°F |

If limonene best earns the “sativa” spot, linalool is the strongest contender for “indica.” Linalool is the main component in lavender essential oils and offers a powerful anxiolytic action through its action on GABAA receptors.

Additional analgesic and anti-cancer properties have some research backing them up, but there’s some promise for the future of linalool research as well.

Still, anyone who has used lavender to calm down in stressful moments or to ease the mind before bed can attest to its anxiolytic and sedative properties.

Linalool is great for when you’re looking for something that takes the edge off rather than getting zooted.

FAQs: THCA vs. THC

Here are some of the most common people ask when comparing THCA to THC:

1. What’s The Boiling Point Of THCA & THC?

When THCA is exposed to heat, it rapidly decarboxylates into THC, which then has an ideal vaporization temperature of 200–230°C (392–446°F) [25]. Higher temperatures run the risk of overheating the THC into its degraded form of cannabinol (CBN), which has benefits but won’t make you feel high.

Additionally, harmful byproducts may form at combustion-level temperatures, suggesting vaporization is safer and more effective. Within the range of temperatures above, vaping THCA could produce higher levels of THC and fewer byproducts.

2. Can You Use THCA or THC Topically?

Topical THCA and THC products like creams, salves, and transdermal patches provide pain and inflammation quickly to a specific area before it spreads throughout the body. Transdermal patches are the best route for topical administration since they provide a slow release of THC into the bloodstream through the skin.

The main benefit of choosing a THCA patch over THC is for people with sensitivities to THC or in prohibitive states. Transdermal patches typically release a low amount of THC over a long period, but this can still be too much for some people who need pain relief.

Lotions, creams, and other topicals are even less likely to lead to a “high” effect regardless of whether they’re THC or THCA. These are beneficial for minor aches, pains, and dry skin but not for more intense conditions.

3. What Does Smoking THCA Flower Feel Like?

Smoking THCA flower, as long as it’s a quality product from a reputable vendor, should feel identical to smoking weed. Since most weed on the market is primarily THCA, the two products are indistinguishable.

The only difference comes down to the labeling, with THCA flower appearing slightly inflated over a similar THC product.

4. Will THCA Show Up On A Drug Test?

Yes, THCA and THC will both appear on a drug test if you’re planning to smoke or vape them. Consuming THCA in a raw form is a little less likely, but it’s still possible, and it would be best not to risk it.

5. Is THCA Flower More Aromatic Than THC?

The advanced curing and processing techniques of THCA flower may give it a higher level of terpenes to give it a better flavor, aroma, and smoke than lower-quality marijuana. Without regulation in the hemp market, however, there are plenty of THCA products on the market with worse quality than a low-tier weed.

Still, it seems to be more likely to find an aromatic “mid” in the THCA market than with THC (in this author’s humble experience).

Subscribe For More 🍄

References

- Dean, J. G., Liu, T., Huff, S., Sheler, B., Barker, S. A., Strassman, R. J., Wang, M. M., & Borjigin, J. (2019). Biosynthesis and Extracellular Concentrations of N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in Mammalian Brain. Scientific Reports, 9(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45812-w

- Filer, C. N. (2022). Acidic Cannabinoid Decarboxylation. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 7(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2021.0072

- Moreno-Sanz, G. (2016). Can You Pass the Acid Test? Critical Review and Novel Therapeutic Perspectives of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid A. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 1(1), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0008

- Bautista, D. M., Siemens, J., Glazer, J. M., Tsuruda, P. R., Basbaum, A. I., Stucky, C. L., Jordt, S.-E., & Julius, D. (2007). The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature, 448(7150), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05910

- Wang, M., Wang, Y.-H., Avula, B., Radwan, M. M., Wanas, A. S., van Antwerp, J., Parcher, J. F., ElSohly, M. A., & Khan, I. A. (2016). Decarboxylation Study of Acidic Cannabinoids: A Novel Approach Using Ultra-High-Performance Supercritical Fluid Chromatography/Photodiode Array-Mass Spectrometry. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 1(1), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0020

- Nadal, X., del Río, C., Casano, S., Palomares, B., Ferreiro‐Vera, C., Navarrete, C., Sánchez‐Carnerero, C., Cantarero, I., Bellido, M. L., Meyer, S., Morello, G., Appendino, G., & Muñoz, E. (2017). Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid is a potent PPARγ agonist with neuroprotective activity. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(23), 4263–4276. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14019

- Martin, H. (2010). Role of PPAR-gamma in inflammation. Prospects for therapeutic intervention by food components. Mutation Research, 690(1–2), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.09.009

- Palomares, B., Ruiz-Pino, F., Garrido-Rodriguez, M., Eugenia Prados, M., Sánchez-Garrido, M. A., Velasco, I., Vazquez, M. J., Nadal, X., Ferreiro-Vera, C., Morrugares, R., Appendino, G., Calzado, M. A., Tena-Sempere, M., & Muñoz, E. (2020). Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A (THCA-A) reduces adiposity and prevents metabolic disease caused by diet-induced obesity. Biochemical Pharmacology, 171, 113693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113693

- Verhoeckx, K. C. M., Korthout, H. A. A. J., van Meeteren-Kreikamp, A. P., Ehlert, K. A., Wang, M., van der Greef, J., Rodenburg, R. J. T., & Witkamp, R. F. (2006). Unheated Cannabis sativa extracts and its major compound THC-acid have potential immuno-modulating properties not mediated by CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways. International Immunopharmacology, 6(4), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2005.10.002

- Rock, E. M., Sullivan, M. T., Pravato, S., Pratt, M., Limebeer, C. L., & Parker, L. A. (2020). Effect of combined doses of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol or tetrahydrocannabinolic acid and cannabidiolic acid on acute nausea in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology, 237(3), 901–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05428-4

- Bala, A., Rademan, S., Kevin, K. N., Maharaj, V., & Matsabisa, M. G. (2019). UPLC-MS Analysis of Cannabis sativa Using Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), Cannabidiol (CBD), and Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid (THCA) as Marker Compounds: Inhibition of Breast Cancer Cell Survival and Progression. Natural Product Communications, 14(8), 1934578X19872907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X19872907

- Malabadi, R., Kolkar, K., & Chalannavar, R. (2023). Medical Cannabis sativa (Marijuana or Drug type); The story of discovery of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). 5, 4134–4143.

- Tsampoula, I., Zartaloudi, A., Dousis, E., Koutelekos, I., Pavlatou, N., Toulia, G., Kalogianni, A., & Polikandrioti, M. (2023). Quality of Life in Patients Receiving Medical Cannabis. In P. Vlamos (Ed.), GeNeDis 2022 (pp. 401–415). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_39

- Wolinsky, D., Barrett, F. S., & Vandrey, R. (2024). The psychedelic effects of cannabis: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 38(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231209194

- Christensen, C., Rose, M., Cornett, C., & Allesø, M. (2023). Decoding the Postulated Entourage Effect of Medicinal Cannabis: What It Is and What It Isn’t. Biomedicines, 11(8), 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11082323

- Raz, N., Eyal, A. M., & Davidson, E. M. (2022). Optimal Treatment with Cannabis Extracts Formulations Is Gained via Knowledge of Their Terpene Content and via Enrichment with Specifically Selected Monoterpenes and Monoterpenoids. Molecules, 27(20), 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206920

- LaVigne, J. E., Hecksel, R., Keresztes, A., & Streicher, J. M. (2021). Cannabis sativa terpenes are cannabimimetic and selectively enhance cannabinoid activity. Scientific Reports, 11, 8232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87740-8

- Surendran, S., Qassadi, F., Surendran, G., Lilley, D., & Heinrich, M. (2021). Myrcene—What Are the Potential Health Benefits of This Flavouring and Aroma Agent? Frontiers in Nutrition, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.699666

- Jansen, C., Shimoda, L. M. N., Kawakami, J. K., Ang, L., Bacani, A. J., Baker, J. D., Badowski, C., Speck, M., Stokes, A. J., Small-Howard, A. L., & Turner, H. (2019). Myrcene and terpene regulation of TRPV1. Channels, 13(1), 344–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/19336950.2019.1654347

- Rao, V. S. N., Menezes, A. M. S., & Viana, G. S. B. (1990). Effect of myrcene on nociception in mice. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 42(12), 877–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb07046.x

- Maffei, M. E. (2020). Plant Natural Sources of the Endocannabinoid (E)-β-Caryophyllene: A Systematic Quantitative Analysis of Published Literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(18), Article 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186540

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (1993). D-LIMONENE. In Some Naturally Occurring Substances: Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513608/

- Komiya, M., Takeuchi, T., & Harada, E. (2006). Lemon oil vapor causes an anti-stress effect via modulating the 5-HT and DA activities in mice. Behavioural Brain Research, 172(2), 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.006

- Mączka, W., Duda-Madej, A., Grabarczyk, M., & Wińska, K. (2022). Natural Compounds in the Battle against Microorganisms—Linalool. Molecules, 27(20), Article 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206928

- Pomahacova, B., Van der Kooy, F., & Verpoorte, R. (2009). Cannabis smoke condensate III: The cannabinoid content of vaporised Cannabis sativa. Inhalation Toxicology, 21(13), 1108–1112. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958370902748559