Coca Leaf: Plant Medicine or Dangerous Drug?

Coca leaf is used to manufacture cocaine — but in its raw form, it’s viewed as a sacred, health-promoting plant medicine.

Throughout South America, cultures still consider coca sacred — in the Andes, they affectionately refer to it as “mama coca.”

Yet, because of the war on drugs, many parts of the world prohibit the coca plant, often giving it the same classification as cocaine.

But the coca plant and refined cocaine are entirely different substances. Classifying these two things as the same is illogical and ultimately leads to more harm than good.

The coca plant has a long history of use — some experts believe it was used more than 8000 years ago. And it’s still widely used today in regions where it grows naturally.

Modern science supports the idea that the coca plant has a lot of health benefits to offer. In this article, we will cover coca’s origins and cultural significance, potential benefits, legality, and how to chew coca leaves and make coca tea.

What is Coca Leaf?

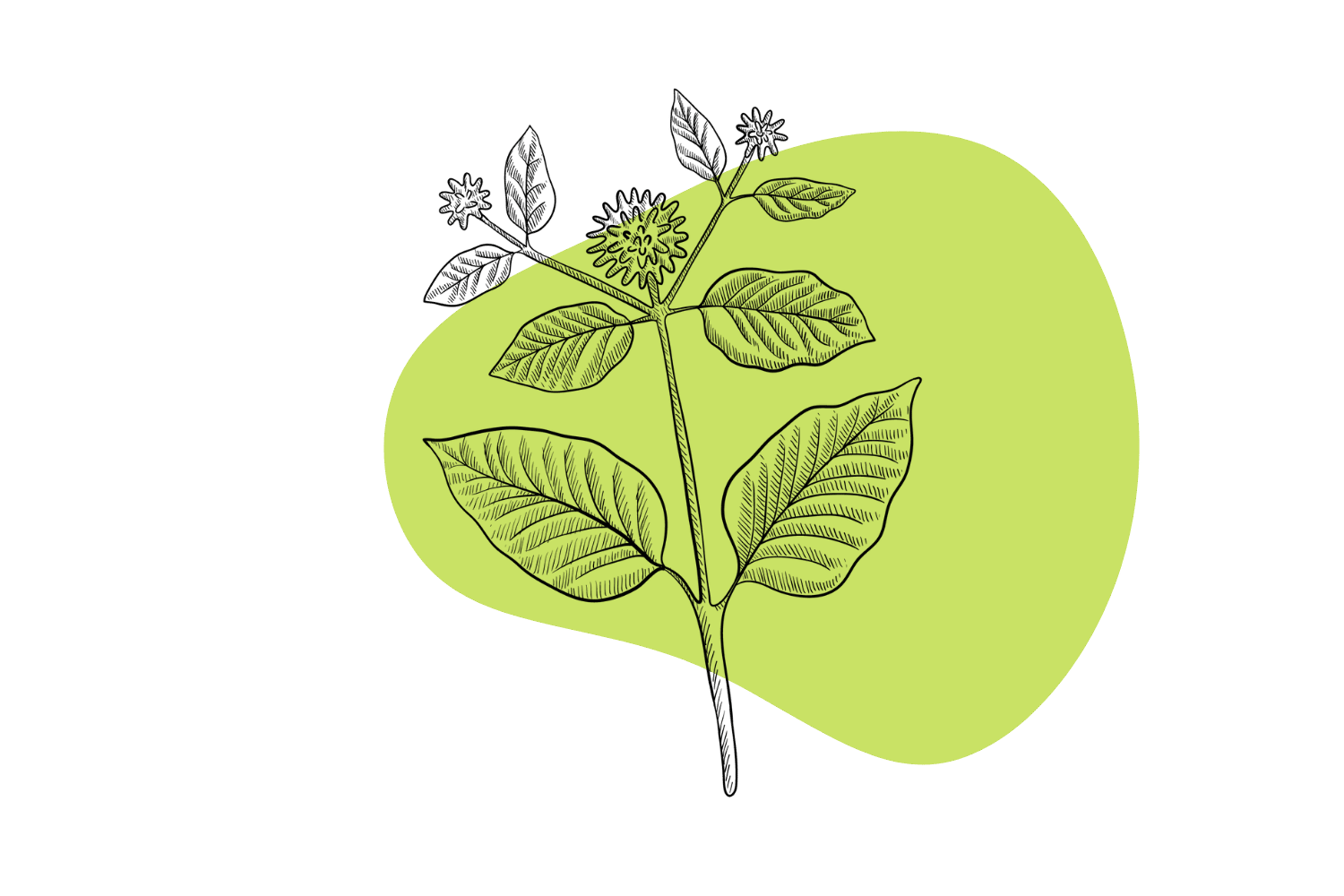

Coca leaves come from the coca plant — a small tropical shrub from the Exythroxylum family. There are several varieties, with the most commonly cultivated being Exythroxylum coca.

Coca leaves are typically chewed as a mild stimulant, giving energy and suppressing appetite. Coca tea is often given to travelers at high elevations in the Andean mountain range to prevent altitude sickness.

Cocaine is also derived from the coca and is one of 14 alkaloids the plant produces. The leaves of coca contain 0.13- 0.76% of the cocaine alkaloid [1].

Concentrations depend on the variety of the coca plant and its age and likely vary across regions, reportedly being higher in Bolivia. Great quantities of coca are grown throughout South America to produce cocaine, with production on the rise and showcasing the ineptitude of the drug war.

What Do Coca Plants Look Like?

The coca plant is about 1–3 m high with dark green leaves, rough reddish bark, and thin branches. Flowers appear in small, clustered groups and are ivory-colored with an almond-like smell. Reddish berries and round seeds also appear on the plant.

Where Does Coca Come From?

Many believe coca to be native to the eastern slopes of the Andes in South America [2]. Inca legend stated coca was a gift from the sun god Inti [3]. Ethnobotanists have found evidence for the use of coca throughout Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina, and Chile.

Pre-Inca civilizations like the Wari used coca. Researchers have found evidence of burial sites containing mummies with coca in their mouths, along with speculation they cultivated the plant [4]. The Inca civilization treated coca as sacred and conquered tropical regions to cultivate the plant as they could not grow it at high elevations.

Often, the Inca empire restricted the use of coca to certain classes and vocations in the Inca empire. Rulers, priests, and shamans used it in ceremonial contexts, the military consumed it during combat, and Inca messengers chewed it during rapid travel over the mountains.

Coca was traditionally carried in a woolen sack and was likely a luxury.

Early missionaries viewed coca as a bad habit when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America [5]. Later, the Spanish saw utility in coca as a stimulant and appetite-suppressant for workers on farms or in mines.

After this, the Spanish began to include coca leaves as pay for workers, issued a large tax on coca, and forced labor for sometimes days at a time.

Modern Use of Coca in Peru and South America

Coca remains an integral part of life for the people of the Andes for work and carries spiritual significance to this day. It is not uncommon to see farmers, miners, and many others with swollen cheeks full of coca leaves.

Throughout the Andes, residents practice a ritual known as “K’intus” [6]. To perform it, participants hold three coca leaves between their fingers in the shape of a cross. The leaves are gently blown over with intention and cast into the air as an offering to the earth — meaning both a physical place and the earth’s mother known as “Pachamama.”

Offerings to ancestral spirits associated with various locations like mountains or “Apus” are also common. Some shamans of the Andes claim to divine the future with coca leaves and will still toss them in the air and observe the resulting patterns. Legends state only shamans who have survived lightning strikes possess the power to work with coca leaves in this way.

Benefits of Coca Leaves & Traditional Uses

Despite hundreds of years of stigma in Western society, coca has a host of ethnobotanical uses, many of which are now backed by science [7].

Indigenous use of coca varies across regions, with some examples being:

- Stimulant — Coca has a long history of use in the prevention of hunger, thirst, and fatigue and for improving mood. Those who partake may chew the leaves or drink them as “mate de coca,” similar to how you might use coffee [8].

- Altitude Sickness — Coca leaves for altitude sickness are a common remedy for travelers of the high Andes. Research has shown biochemical changes which may result in the body using fatty acids for energy, associated with improved endurance [9].

- Anesthesia — Cocaine is a well-established local anesthetic creating numbness after consumption or topical application. The numbing sensation of coca led to the extraction of cocaine in 1860 by Albert Niemann for use as a local anesthetic [10].

- Nutritive — Coca contains many vitamins and minerals, but one would need to consume a great deal for real benefit. However, it is a significant source of calcium and is a potential supplement for people with dairy intolerance [11].

- Analgesic — For pain relief, people may chew coca, drink it as tea, apply it topically, or make it into a potent decoction. This is often for relief from headaches, sore throat, arthritis (rheumatism), wounds, childbirth, and broken bones [12].

- Antimicrobial — The topical paste is also applied to open wounds and as a treatment for abscesses and boils. Ethanol extracts from coca leaves have been shown to offer notable antibacterial properties [13].

- Fractures — Coca may be a treatment for broken bones. Modern analysis has confirmed coca has calcium and iron content, perhaps aiding bone health [14]. Coca is also thought to keep teeth white and is even in some toothpaste.

- Asthma & Colds — Coca in various forms, often mixed with other ingredients, may aid in the treatment of asthma, breathing difficulties, colds, and inflammation of the throat.

- Stomachache — Typically taken as a tea, coca is widely used as a remedy for upset stomach, indigestion, and gas.

- Malaria — Coca tea is sometimes given to malaria patients to reduce fever.

- Aphrodisiac — Sometimes couples having difficulty conceiving take a strong decoction of coca as an aphrodisiac.

Coca Leaf Side Effects

While this list of coca’s traditional uses is extensive and far from exhaustive, it is not universally accepted as a healthy choice. Early reports indicated researchers saw this plant as a potential superfood.

However, a more recent analysis of coca leaves nutritional potential could not find this to be the case. The authors of the study concluded coca leaves offered “no significant advantage in mineral content … [and] no nutritional advantage over other leaves” [15].

It then goes on to caution about studies that showed rats fed coca developed liver and heart problems, among others. Outsiders of Andean culture have long seen the constant chewing of coca leaves as an addiction. Residents of this culture often covet coca and see it as a necessary luxury — similar to how we treasure coffee. However, the comparison to cocaine is neither fair nor accurate.

The amount of cocaine in the average amount of coca leaves is far below levels considered dangerous. The alkaloid content of coca leaves is between 0.23% to 0.96% [16].

At these levels, one would need to consume over 100 g of coca to experience toxic effects. This number is over double the amount chewed on average [17].

Is the Coca Plant Legal?

Cocaine is a Schedule 1 drug, viewed by authorities as dangerous with a high potential for addiction and no medical use. Since coca leaf is the source material of cocaine, it has earned a spot as a Schedule 1 restricted substance around the world.

The UN Single Convention for Narcotic Drugs 1961 made it illegal to grow or possess coca leaves in the US and abroad, except for medical uses. Countries around the world lump coca leaves in with cocaine and criminalize it similarly.

Still, it is either legal or tolerated to grow or possess coca leaf in limited quantities in the following countries:

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Chile

- Colombia

- Peru

- Venezuela

How to Chew Fresh Coca Leaves

Coca leaves are readily available in markets throughout South America. The sun-dried oval leaves are easily recognizable inside small plastic bags.

Steps for chewing coca leaf:

Step 1: Chew the Fresh Leaf Into a Pulp

The taste of coca is fairly bitter and astringent, although not altogether unpleasant.

Step 2 (Optional): Add a Pinch of Alkalizing Agent

Many simply chew the leaves; however, to facilitate greater absorption of cocaine, some add alkaline substances. Ancient examples are lime from burning rocks, sea shells, ashes from burning tree bark, or the stalks of quinoa plants.

Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) also works.

In certain regions, people still carry these alkaline substances in a special gourd. Users plunge a wet stick into the gourd to attach alkaline powder, then delicately put it in their mouth, taking care not to burn their cheek if the substance is corrosive, like lime.

Greater absorption of cocaine is noticeable using this method, such as pronounced numbness.

In the Amazon, some choose to toast and grind coca into powder and mix it with the alkaline ashes of other plants. The name of the resulting product is ypadu or mambe. To use, scoop this powder up and place it between the teeth and cheek like a coca quid.

Step 3: Hold the Pulpy Wad Between the Teeth & Cheek, Then Discard

As you produce saliva, your body absorbs cocaine and other active ingredients through the mucosal membranes into the blood. The effects should kick in within about 5 minutes.

Then swallow the juices, keeping the coca leaves in your cheek for roughly 30 minutes, depending on the size, and then discard.

How to Make Coca Tea

Coca tea is another simple option for consuming coca leaves — both fresh and dried.

Outside of South America, the most common form of coca leaf is the dried powder, which is hard to apply via chewing. Most people either encapsulate it or brew it into a tea using the following steps.

Step 1: Bring Your Water to a Boil

Coca is resistant to heat, so you can choose to boil your water or allow it to reach a more comfortable 80ºC (176ºF).

Step 2: Measure Your Dose of Coca

If using dried leaf powder, weigh out around 1 gram, then add it to a paper teabag or simply stir it into the water. Adding directly to the water maximizes the effects, but it can leave a chalky aftertaste. If you dislike this taste, teabags work just fine too.

If you’re using fresh leaves, add about three leaves to the water.

Step 3: Allow the Coca Leaf to Steep for Several Minutes

Wait about 2 or 3 minutes for the active ingredients to diffuse into the water before you drink it. You can re-steep 3 or 4 times before the coca starts to lose its potency.

Does Drinking Coca Tea Show Up on a Drug Test?

Drinking coca tea will certainly show up on a drug test for cocaine — especially within the first 24 hours or so. Positive test results become much less likely after 36 hours and are virtually nonexistent after about three days.

Cocaine is notoriously difficult for drug screens to catch since the body processes it so quickly. Still, when researchers gave participants a standard cup of coca tea with commercial teabags sourced from Peru, urine samples suggested cocaine use [18].

After passing through the liver, cocaine breaks down into a metabolite called benzoylecgonine — this is what tests are screening for. At the two-hour mark, the urine of all participants showed positive benzoylecgonine amounts, implying cocaine use.

After 36 hours, the majority of participants in the study still showed positive results.

Coca: Sacred Plant or a Dangerous Drug?

Coca has been integral in rituals, work, and medicine for an incredibly long period of history. Stimulant use happens across cultures and continents, such as the staple cup of coffee many enjoy. In a traditional context, coca is an extremely prized plant, as its list of practical uses is long, and its cultural role is still significant.

Yet, in the modern world, the international war on drugs overshadows the potential of coca use. Despite billions of dollars and decades of legislation encouraging reckless tactics like the mass spraying of glyphosate, cocaine production continues to rise.

All while classifying the coca plant as a Schedule 1 drug alongside heroin and methamphetamine.

Like many plants, coca has become a commercial commodity, far removed from its ancient roots. It should be clear, however, that the coca leaf has many benefits, a rich history, and a relatively safe profile.

For proof of this, look to the generations of humans consuming this plant without major incidents.

References

- 1. Advances in chemistry and bioactivity of the genus Erythroxylum—PubMed. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35426005/

- 2. Plowman, T. (1979). Botanical perspectives on coca. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 11(1–2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1979.10472095

- 3. Coca: The Sun God’s Anesthetic Leaves. (2021). Anesthesiology, 135(2), 291–291. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003894

- 4. Ancient Use of Coca Leaves in the Peruvian Central Highlands | Journal of Anthropological Research: Vol 71, No 2. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.3998/jar.0521004.0071.204

- 5. Lloyd, J. U. (1913). Coca—“The divine Plant of the Incas.” The Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (1912), 2(10), 1242–1244. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3080021005

- 6. Davis, W. (2007). Light at the Edge of the World: A Journey Through the Realm of Vanishing Cultures. Douglas & McIntyre.

- 7. Ethnobotany of the Andes | SpringerLink. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-3-030-28933-1

- 8. Stolberg, V. B. (n.d.). The Use of Coca: Prehistory, History, and Ethnography. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2011.573310

- 9. Casikar, V., Mujica, E., Mongelli, M., Aliaga, J., Lopez, N., Smith, C., & Bartholomew, F. (2010). Does Chewing Coca Leaves Influence Physiology at High Altitude? Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 25(3), 311–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-010-0059-1

- 10. Grzybowski, A. (2007). [The history of cocaine in medicine and its importance to the discovery of the different forms of anaesthesia]. Klinika Oczna, 109(1–3), 101–105.

- 11. Coca Myths | Transnational Institute. (2023, April 21). https://www.tni.org/en/publication/coca-myths

- 12. Calatayud, J., & González, Á. (2003). History of the Development and Evolution of Local Anesthesia Since the Coca Leaf. Anesthesiology, 98(6), 1503–1508. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200306000-00031

- 13. Loyola, D., Mendoza, R., Chiong, L., Rueda, M., Alvítez-Temoche, D., Gallo, W., & Mayta-Tovalino, F. (2020). Ethanol extract of Schinus molle L. (molle) and Erythroxylum coca Lam (coca): Antibacterial properties at different concentrations against Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study. Journal of International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry, 10(5), 579. https://doi.org/10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_237_20

- 14. Trigo-Pérez, K., & Suárez-Cunza, S. (2018). Evaluation of the effect of coca leaf powder consumption on bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia, 63(4), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v63i2023

- 15. Penny, M. E., Zavaleta, A., Lemay, M., Liria, M. R., Huaylinas, M. L., Alminger, M., McChesney, J., Alcaraz, F., & Reddy, M. B. (2009). Can Coca Leaves Contribute to Improving the Nutritional Status of the Andean Population? Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 30(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482650903000301

- 16. Plowman, T., & Rivier, L. (1983). Cocaine and Cinnamoylcocaine Content of Erythroxylum Species. Annals of Botany, 51(5), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086511

- 17. Heitzeneder, A. (2010). The Coca-leaf—Miracle good or social menace? https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Coca-leaf-miracle-good-or-social-menace-Heitzeneder/5fa998752b9865b176cf84cd50509e7de7e3ad4b

- 18. Mazor, S. S., Mycyk, M. B., Wills, B. K., Brace, L. D., Gussow, L., & Erickson, T. (2006). Coca tea consumption causes positive urine cocaine assay: European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(6), 340–341. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mej.0000224424.36444.19