Inipi: The Traditional Sweat Lodge Ceremony of Purification

Inipi is like a sweat lodge… but better.

Aho Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ (Hau, Mitaku Oyasin), (Aho for short) is a great blessing in the Lakota language. It means, ‘we are all related.’

It’s only fitting to begin with ‘Aho!’ since this greeting is said at the beginning and end of all traditional Lakota inipi sweat lodge ceremonies.

For an objective observer, the sweat lodge appears to be an experience of what Westerners define as ‘hydrotherapy,’ but nothing could be further from the truth.

Every aspect of the inipi ceremony is a prayer. A sweat lodge is an offering of energy, time, and spirit, to and for the Great Mystery.

According to Paul GhostHorse, for the Lakota people, ‘[Sweat lodge] is our church, our hospital and our university [1].’

A sweat lodge is a place for prayer, a place for healing, and a place for learning. Its very nature declares reverence.

As with other indigenous rituals, the steps involved in a sweat lodge ceremony have been passed down by word of mouth and experience. This seems to preserve the ethereal and sacred nature of the practice, but it makes it difficult to research and compile scientific evidence on the topic.

Inasmuch, this article (written with much humility) is an attempt, not to expose the mystery, nor minimize the grandiosity of the ritual, but rather to shed a light of understanding and help others see a different way of life with awe and compassion.

What Is A Sweat Lodge?

The inipi ceremony, short for Inipikaga, is a customary ritual from the Lakota or Teton Sioux people, whose lands are currently located in North and South Dakota.

This sacred cleansing ritual has been preserved thanks to Native peoples, over many generations, with much sacrifice.

The ritual can stand on its own as a form of prayer. Even the building of the lodge itself is an opportunity to pray. Inipi is also often performed as a precursor to, or aspect of, other indigenous rituals such as the Sun Dance, Moon Dance, Vision Quest, etc.

The Native American sweat lodge, also referred to as Tunkan Ti, the house of the Stone People, is a form of ancient technology, like meditation, breathwork, or yoga. It is a practice of community prayer for healing.

The sweat lodge is considered an offering to the spirit of the universe, Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, or the Great Mystery [2].

It’s a purification ritual where community members cleanse through sweat as a symbol of surrender and a form of offering.

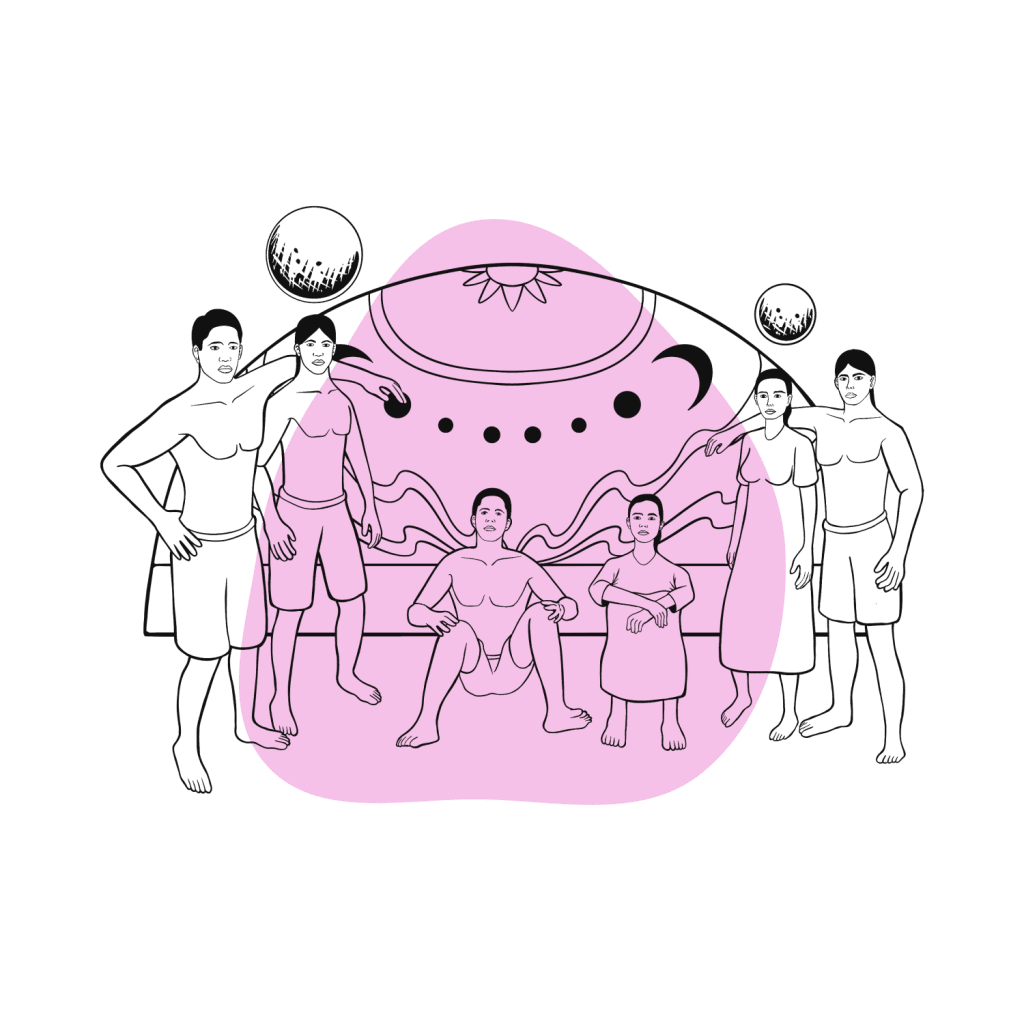

The lodge is often referred to as a womb and an opportunity to experience ‘rebirth.’ The dark, warm space of the lodge and its shape can be viewed as a replica of a womb. Those who wish to pray inside the sweat lodge are encouraged to crawl inside on hands and knees and embody the innocence and feebleness of a baby.

It’s also considered a space to reconnect with our relatives, ancestors, and others in our lineage, including different forms of existence. This underscores the importance of acknowledging our sacred connection with all relatives through the declaration, ‘Aho Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ,’ because through the lodge we come to see that truly, ‘we are all related.’

Inipi, like many indigenous practices, is mysterious, spiritual, and grand. Participating in a sweat lodge ceremony is an act of devotion that shows respect for not just the Lakota people, but for all of existence.

Step By Step Guide to A Sweat Lodge Ceremony

There are many steps involved in the sweat lodge ceremony and many particular nuances.

Traditions vary from culture to culture and from facilitator to facilitator, as do the order of events, procedures, and specifics. Though this list may not be exhaustive, it should help to illustrate the process and help curious individuals to understand what the experience is like.

1. Lighting The Sacred Fire

On the physical level, to begin a sweat lodge, a fire is lit.

Particular stones, preferably lava stones, sometimes called ‘grandfather stones,’ are prayed over, and placed inside the center of the fire, or ‘the fireplace.’

In some settings, the stones are called Tunkashila, which refer to the ‘Grandfather Spirits.’ In this way, ‘Tunkashila’ is also used to refer to any Great Spirit that personifies sacredness and wisdom.

Usually, one stone is placed into the fire in honor of each of the four directions, as well as one stone offered to each of the elements. It’s common to include 28 stones in the sweat lodge fire, or seven for each round, though this varies greatly from lodge to lodge.

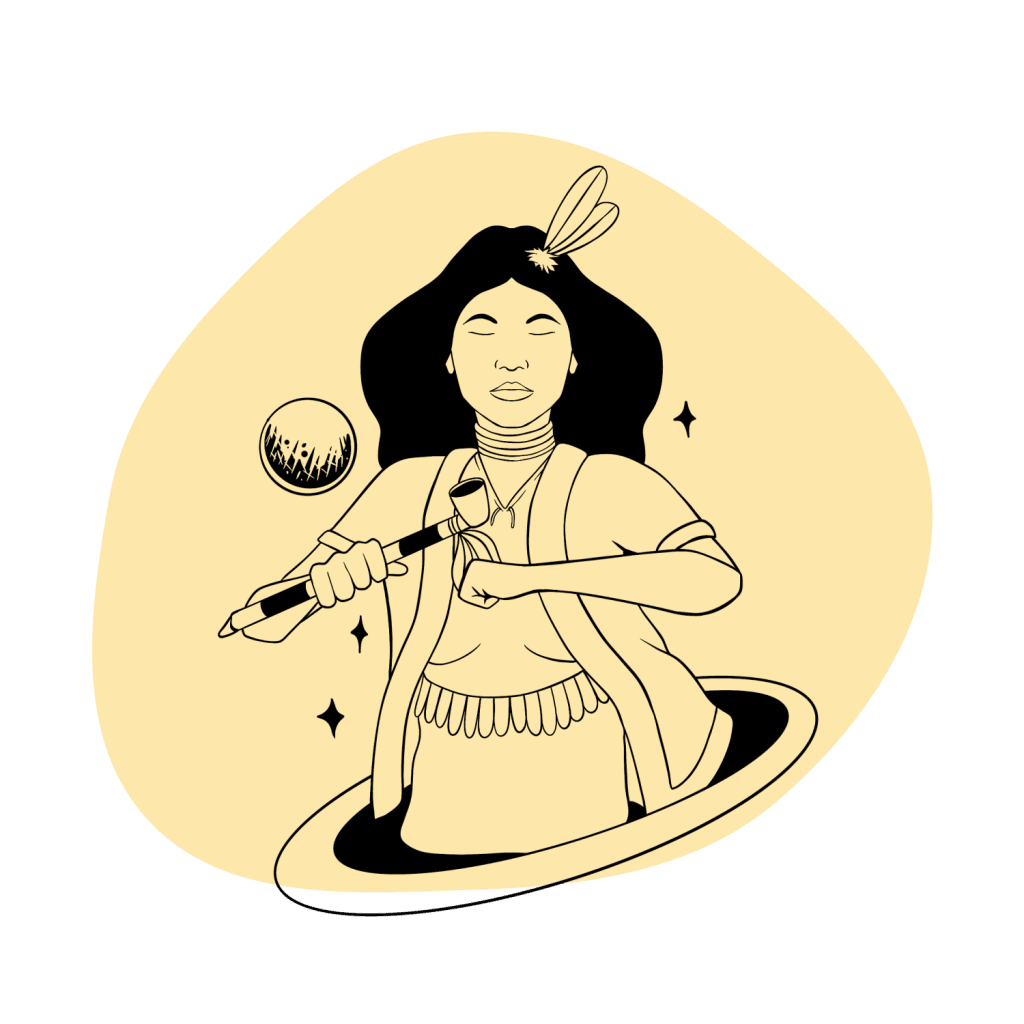

2. The Sacred Pipe & The Altar

While the stones are heating, the water pourer, or the facilitator of the ceremony, fills the sacred pipe with holy tobacco and sings ‘pipe filling songs,’ then places the pipe on an altar.

The altar is adorned with special possessions which may include sage bundles, a buffalo skull, eagle feathers, a two-pronged staff, or variations of these kinds of valuables.

3. Locating The Sweat Lodge

The location of the lodge is important, as is the door’s direction.

According to certain traditions, the door should open towards the east. Others suggest that the doorway should face the south. Others still change the direction of the door depending on the season.

Whichever way the door faces, the sacred altar and the fireplace should be visible through the doorway from inside of the sweat lodge.

The pathway between the sweat lodge door and the fire is considered a holy path. No one should cross between the fire and the doorway but rather walk around it.

Typically, a blanket covers the doorway and conceals the heat and darkness during the ceremony.

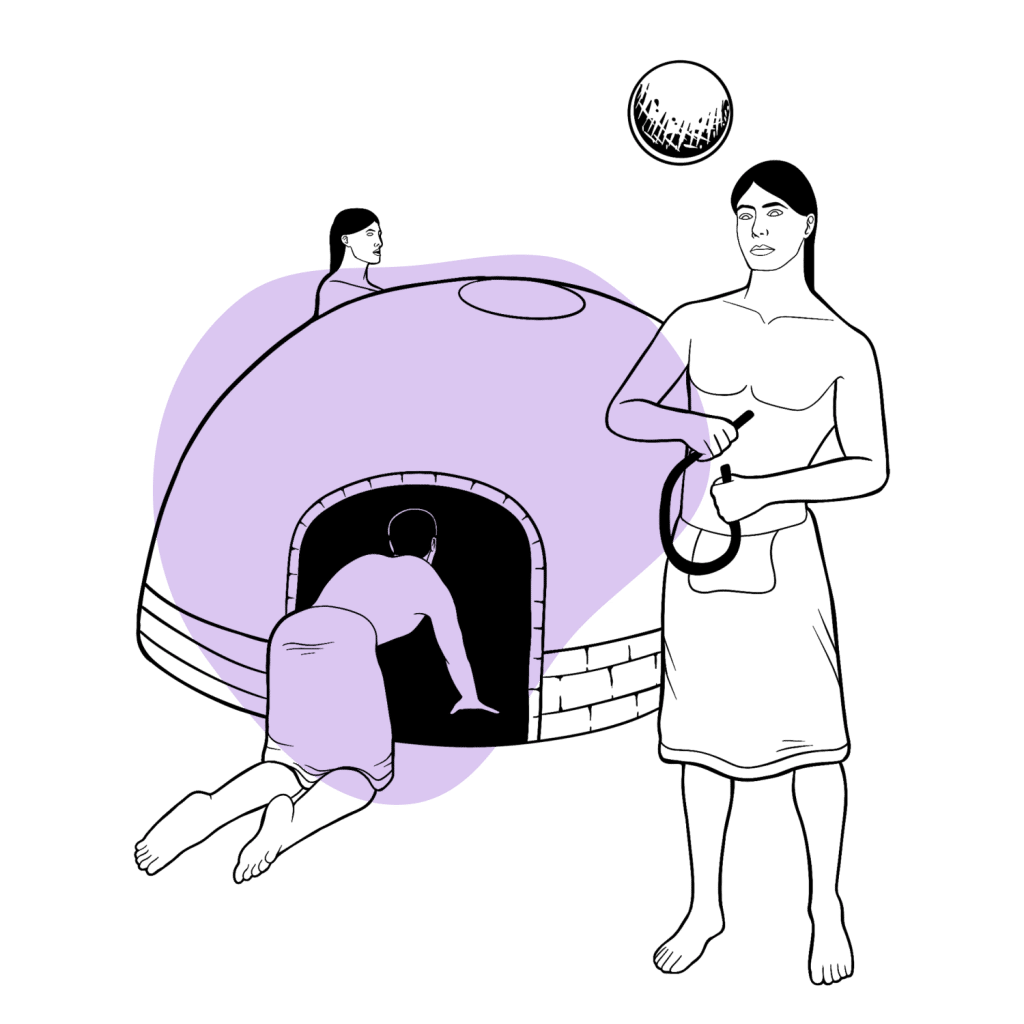

4. Entering The Lodge

Once the grandfather stones are hot, after about 90 minutes to two hours, community members are invited to cleanse themselves with a cedar or sage smudging. Then, they begin to enter the lodge, crawling on hands and knees in a clockwise direction.

The lodge is a small structure usually built of sticks called ribs. Traditionally, the ribs are covered with buffalo hide; however, moving blankets are usually used today.

Although it depends on the size of the lodge and how many people are in attendance, it can be a tight fit. Some individuals describe a sense of claustrophobia from the tight quarters. The lodge certainly isn’t designed to be comfortable.

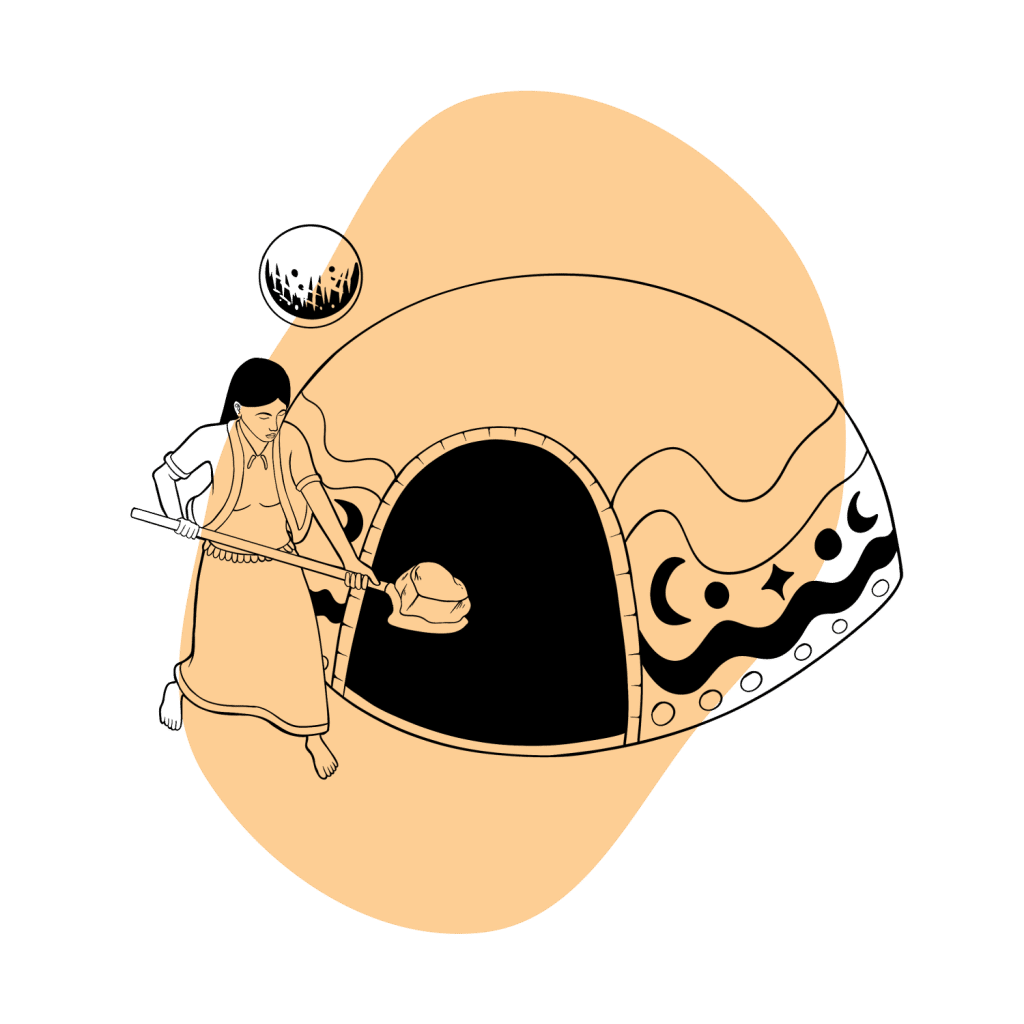

5. Bringing The Stones Into The Sweat Lodge

When everyone is inside, the firekeeper brings a specific number of hot stones from the fire into the lodge. Inside, someone is prepared to ‘catch’ the hot stones and place them in the center, usually into a crater that has been dug out to hold the stones. Deer antlers are often the tool of choice used to catch the hot stones and place them in the right spots.

As the stones enter, they are blessed with holy herbs such as sage, cedar, and copal. Then, a large bucket of water is brought inside, which will be used to activate the stones so they can rapidly release their heat.

Once the stones are inside, the firekeeper(s) enter the lodge and close the door so the round can begin.

6. The Water Pourer

Next, the water pourer may introduce themself, offer a prayer or intention, and then begin to activate the stones. A water pourer could be seen as the shaman of the sweat lodge.

Water, known as Mní wičhóni in Lakota, is poured on top of the hot stones which creates a sauna-like experience for the individuals inside. It is said that the sound produced by pouring water onto the hot stones is the Tunkashila whispering to each other.

Typically, a drum crafted with a deer or buffalo hide is played inside the lodge, as well as a rattle or a shaker to accompany medicine songs. The style of songs, how many songs, and who will lead the songs, usually depends on the lineage of the water pourer. Normally, there are four songs sung during each door.

The lodge tends to get progressively hotter as the ceremony continues and more hot stones are brought inside. A water pourer is said to be very compassionate who splashes some of the Mní wičhóni on the participants to help them cool off.

7. Rounds of The Sweat Lodge

The ceremony generally lasts for four doors or four rounds; one for each of the four directions. According to some traditions, there is a fifth direction: inward. In other cases, there are considered to be seven directions. This includes the four directions, Father Sky, Mother Earth, and the Creator.

Occasionally, there is a fifth door during the sweat lodge, called the ‘buffalo round’ or the ‘firekeeper round.’ In other settings, there may be as many as seven doors.

Between each round, the door is opened, and the water bucket (which may now be empty) is taken out. The firekeeper exits the lodge to bring more hot stones inside. Often during these transitions, the water pourer invites community members to offer prayers to the Great Mystery, silently or aloud.

The bucket is refilled, and the entire process is repeated until all of the grandfather stones have been brought inside the inipi to share their ancient wisdom.

8. Rebirth From The Womb

After the last round of the inipi, when all of the water has been poured, the final door is opened at the proclamation of Aho Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ.

The remaining heat is allowed to escape through the doorway, and the water bucket, drums and instruments, and other sacreds are removed from the lodge.

One by one, individuals are invited to crawl out of the lodge and experience the sensation of rebirth, having expressed their intentions, prayers, and devotions in the heat of the experience.

9. Closing The Ceremony

When everyone has emerged from the lodge and had a chance to neutralize body temperature, gatherers are called together to share in closing prayers and the smoking of the sacred pipe, the čhaŋnúŋpa.

Ceremonial closing songs or songs of gratitude are sung at this point.

10. Smoking The Chanupa

The holder of the chanupa, usually the water pourer, and anyone else in attendance who has accepted the great privilege of carrying a chanupa, like fire keepers, or drummers, now light the tobacco and pray with it.

The tobacco they light is the same holy tobacco that was prayed over at the beginning of the ceremony, and that sat in the chanupa on the sacred altar throughout the ceremony.

It is said that the tobacco takes on all of the prayers of everyone who prayed inside the lodge, both silently and aloud. Thus, the tobacco is quite potent with prayer.

In some instances, those who prayed in the lodge stand in a circle, during the smoking of the chanupa. The pourer may ‘knight’ each person on the shoulders with the pipe’s stem, and blow holy tobacco smoke in their direction. This is symbolic of blessing their rebirth.

Some pourers pass the pipe around for each person to smoke and bless themselves.

Traditions of The Sweat Lodge (Inipi) Ceremony

There are a few specific traditions that many chanupa carriers and water pourers follow when building a lodge, or preparing for an inipi ceremony.

Although traditions vary across cultures, the overall process includes similar and rituals.

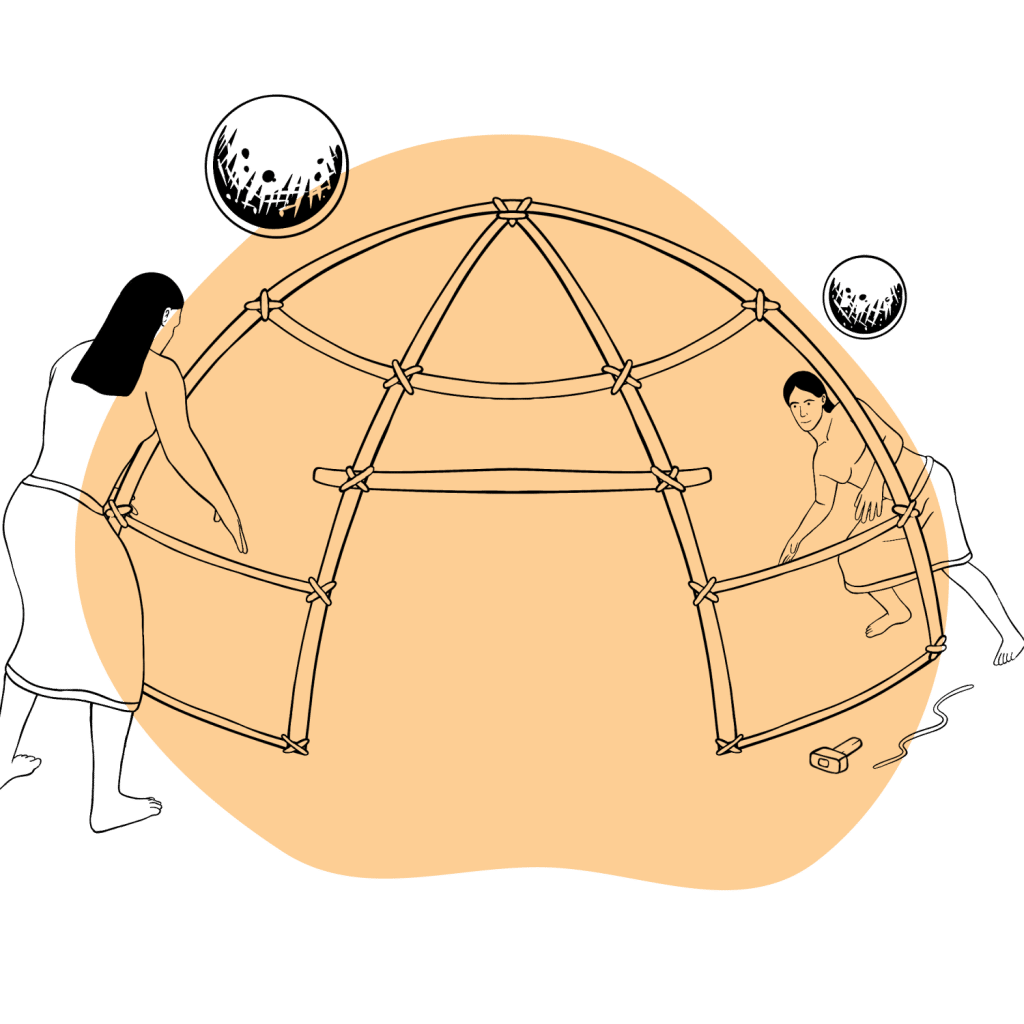

Building A Sweat Lodge

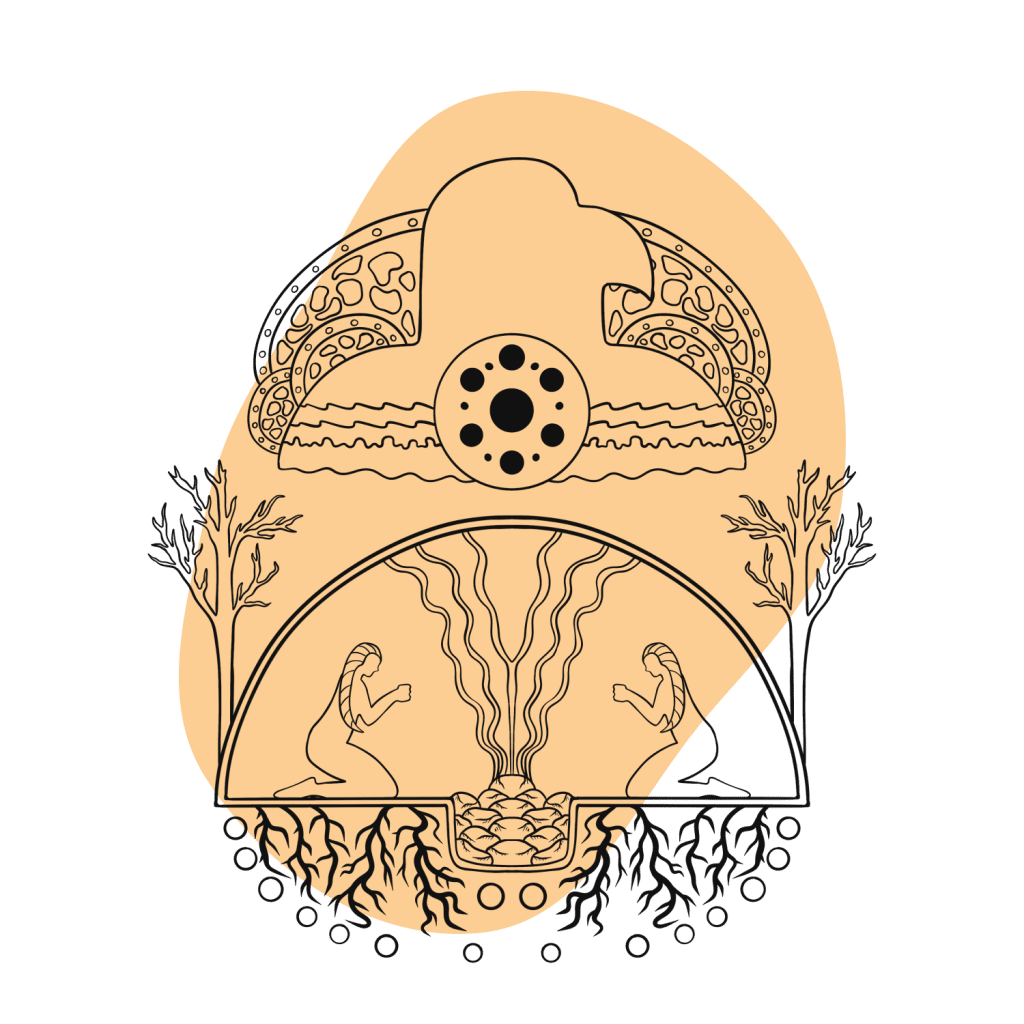

It quite literally ‘takes a village’ to build a sweat lodge.

To begin, large beams of wood are collected. As with many indigenous ritual practices, when collecting ‘gifts’ from the Earth, it is important to offer gratitude and energy exchange. This can be achieved through prayer, song, or placing holy herbs at the site of the collection.

Traditionally, cottonwood is used to build the frame, the ‘ribs’, of the structure. However, this depends on culture and availability.

A location is selected for the lodge, a circle is outlined and measured, and the exact placement of the ribs is determined by digging holes in the Earth where the bases of the wooden beams will go. Cornmeal or tobacco is offered into the holes.

Once all the beams are in place, community members work together —with much patience— to carefully bend the wood beams into place. Some individuals use their bodies to brace the wood, while others use rope or hide strings to tie the beams together into a crosshatch pattern.

When the inipi framework is complete, it looks like an upside-down basket and has been likened to a turtle shell.

A hole is dug in the ground in the center of the structure where the hot stones will land during the ceremony.

Dressing The Lodge

Now that the frame is constructed, it must be covered. This preserves and collects the heat that will transfer from the fire to the stones, through the water and air into the relatives inside the sweat lodge.

Historically, buffalo hide —buffalo being one of the most sacred and revered animals in the Native traditions— or the leathery skin of the animal, is used to cover the ribs. Today, it is more common to use woven textiles or moving blankets.

Traditionally, women are tasked with the role of dressing the lodge. As with any long skirt or dress, the lodge should be completely covered by the textile, extending down to the floor and even a few inches beyond the base of the beams.

This is done to achieve complete darkness and preserve the heat inside. Covering the lodge in this way is also seen as a practice of modesty, a theme typical of the inipi.

Prayer Ties

Prayer ties are made for many Native traditions as an offering to the Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit. As the name implies, while making prayer ties, it’s important to be focused, and infuse prayers and intentions into each pouch.

Prayer ties are small bundles of tobacco or cornmeal wrapped in fabric squares of different colors. Each pouch is tied together to create a long string of prayers. The number of pouches and colors vary from one tradition to the next, and from one ceremony to the next.

The completed string of prayer ties is brought into the sweat lodge and wedged between the ribs overhead to hear the prayers throughout the ceremony. At the end of the ceremony, it is customary to throw the prayer ties into the sacred fire to complete the offering.

In the Lakota tradition, prayer ties follow the colors of the medicine wheel and each represents one of the four directions, a season, and other attributes:

| Color | Direction | Season | Symbolism |

| Black | West | Autumn | Insight and power |

| White | North | Winter | Purity, cleansing, and health |

| Red | South | Spring | Growth and change |

| Yellow | East | Summer | Beginning, inspiration, and light |

The medicine wheel itself is often used as a symbol of the Native traditions and holds many meanings including stages of life, times of day, animals, plants, elements, and more.

Prayer Songs

During inipi ceremonies and other Native rituals, there are usually prayer songs or medicine songs.

According to Paul GhostHorse, ‘Old songs are sung in the same order they have been sung for a thousand years, like a very old, worn and familiar path.’

Songs from the inipi are sung in the Lakota language. In sweat lodges of different — especially new age— origins, many different types of songs are sung in various languages.

The Song Circle organization is dedicated to preserving, sharing, and indexing indigenous medicine and prayer songs from many traditions.

The Four Doors of The Sweat Lodge

Each round of the inipi ceremony, much like the medicine wheel and the colors, is symbolic.

Door 1: A prayer for the Grandfathers, Grandmothers, and the Creator.

Door 2: A prayer for our brothers and sisters, two-legged, four-legged, finned, and winged creatures.

Door 3: Prayers for specific people, places, and things such as our brothers and sisters that are suffering from addictions, heartache, or natural disasters.

Door 4: A prayer for ourselves, our journey, our weaknesses, obstacles, and challenges.

Some water pourers also ascribe elements to each round of the sweat lodge and suggest singing songs to the elements during each respective door.

What To Wear To An Inipi Sweat Lodge

It’s common for men to wear shorts inside the sweat lodge.

It’s suggested that women wear long skirts or long dresses that cover their knees and keep their shoulders covered.

Women In The Sweat Lodge

Depending on the setting, women are encouraged to enter the sweat lodge.

As with many religious and ritual-based practices, if a woman is on her moon cycle (menstruating), she may be asked to refrain from participating in the sweat lodge ritual. This is because she is considered to already be in a purification ceremony.

Ask the water pourer or organizers of the sweat lodge if you may attend the inipi during your period.

Chanupa: The Sacred Pipe

The chanupa, čhaŋnúŋpa, is the true heart of the inipi sweat lodge ceremony, and many other traditional Native ceremonies and rituals.

A chanupa pipe is used to smoke holy tobacco and other herbs to speak out prayers to the Great Spirit. This is because, in the Lakota tradition, tobacco is seen as a medium of communication from the Earth and its beings to the Great Mystery, Wakan Tanka.

As the story goes, The White Buffalo Calf Woman appeared as two Lakota men were on a quest in search of food for the tribe. She was said to be an incarnation of Wakan or holiness.

One of the men fell into deep lust for the woman and as a result quickly turned into a cloud of dust. The other man approached with reverence and the woman explained she was a sacred messenger and would greet his people.

The woman gifted the people the chanupa, one of the most sacred items a person can carry, and taught them the Seven Sacred Rites of Lakota prayer.

Some of the more commonly known sacred rites of Lakota prayer include:

- Inípi: Sweat Lodge Ceremony and Rite of Purification

- Haŋbléčheyapi (Hanblecha): Vision Quest and Rite of Passage

- Wiwáŋyaŋg Wačhípi (Wiwangwacipi): Sundance and Rite of Renewal

The gift of the pipe to the Lakota people was considered auspicious and grand. Henceforth, a chanupa is considered to be one of the most valuable possessions and should carry the spirit of all existence.

The chanupa bowl is made of red stone, and the pipe is made of a wooden stem. The stone represents earth, the stem represents everything that grows upon the earth.

Some chanupas feature a carving of a buffalo in the center, which represents the two and four-legged animals upon the earth. Other chanupas have Wanbli, Eagle feathers that represent the winged creatures of the Earth.

It is said that when you use the pipe to pray, you are praying for everything and with everything.

Teachings Of The Sweat Lodge

The teachings of the traditional Sweat Lodge are many.

From a Native American cultural perspective, one could say simply, ‘everything is everything.’

Through the Native approach, we see the interconnectivity of all life, all time, and all matter. We can refer to the opening sentiment, Aho Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ, and acknowledge ‘all of our relations.’

From this relational standpoint, we begin to see the overarching themes that emerge from the interior space of the sweat lodge, including humility, reverence, surrender, gratitude, resilience, the interrelationship of all life, and modesty. We may also get a sense of the infinite and the finite together as one.

Other Sweat Lodge Traditions From Around The World

Cleansing the body, mind, and spirit through perspiration has merit on a global scale.

Inipikaga is a traditional Lakota sweat lodge, but rituals for purification that include heat and sweat are not unique to the Lakota tradition.

According to Paul GhostHorse, ‘Years ago there was a discovery in Siberia of structures made from the rib bones of mastodons with piles of stones in each center. In Finland, it’s called a sauna.’

Take a look at a few sweat purification rituals from across the world.

Temazcal

The mesoamerican version of inipi is called Temazcal. It comes from a prehispanic Aztec culture.

The ritual is called temāzcalli in the Nahuatl language, which is both endangered and indigenous.

The temazcal is similar to the inipi but may be constructed from adobe, clay, volcanic rock, sand, or other earthen materials rather than ribs.

The ritual follows a similar structure of heating stones and using fire to channel the heat through the air to purify those who have come to pray.

Traditional temazcales can be found throughout Mexico.

Russian Banya

Turkish Baths and Russian Banyas are seen as a place to cleanse the physical body of dead skin and other irritations, though, arguably even more important is the cleansing of the soul, which no shower or bathtub can begin to do [3].

The ritual surrounding a banya experience is not as involved or tribe oriented as an inipi, but there are social aspects to the experience and a mindset that suggests that we can find our place in the world through being together.

Moroccan Hamam

Like the Russian Banya, the Hamam, or Moroccan Bath House is less community-oriented than an inipi ceremony, but still maintains elements of both purification and socialization. It’s popular to choose to go to the bathhouse on your own, but there is positive interaction with others once inside the steamy temple-like space.

More than a simple rinse, a visit to the Hamam is a chance to scrub yourself clean of the old, withering layers, and renew. In this way, the Hamam is a variation of rebirth from the womb.

Preparing The Body & Mind For An Inipi Ceremony

Before a sweat lodge ceremony, it is a good idea to be well-rested and, more importantly, well-hydrated!

Drink plenty of water in the days and hours leading up to the sweat lodge. Aside from water, tea, natural juice, and coconut water can be great ways to bolster electrolytes and keep fluids in the body, since you’ll perspire quite a bit during the ceremony.

Eat light, minimally processed foods, like fruits and vegetables or soups.

Though formal fasting is not necessary, it’s a good idea to stop eating an hour or two before entering the lodge and allow the body to digest.

Remember to bring water and fruit for after the lodge too, to restore some of the lost fluids.

Set An Intention

It’s a good idea to nurture your mind and heart before a sweat lodge inipi ceremony with a clear intention or prayer. Meditate on what or who you are praying for, and bring those sentiments into the lodge energetically.

In moments where the heat seems unbearable, it can be comforting to reflect on the reason behind your presence at the ceremony and why you have chosen to pray in this way.

What Are The Benefits Of A Sweat Lodge?

The benefits of a sweat lodge are many.

Although the western view that ‘hydrotherapy’ and perspiration can help cleanse your physical body and rid you of various illnesses or ailments may be true, the real benefits of an inipi sweat lodge lie within the heart and the collective consciousness.

By crawling into the inipi, we come back to a sense of humility and have the opportunity to remember our place and remember who we are. It can be seen as a reset to come back to our truest, innermost ideals, not as ego-driven individuals, but rather as whole, embodied beings.

Through the sweat lodge, we are transported to another realm and another time. We can disconnect from the mundane and transcend to a space of connection with all of creation and all of existence.

Inipi: Ritual Purification In A Sweat Lodge

The holy tradition of the inipi sweat lodge is cloaked in as much mystery as the buffalo hide and blankets that cover the lodge itself.

Limited written or scientific information is available on the ritual, but the spirit of the inipi practice goes beyond words just like many other sacred practices.

The meaning and intention of the inipi can be seen in every moment of the ceremony, before the lodge is even built.

Sweat purification may not be unique to the Lakota tradition, but the inipi ritual and the reverential approach to every part of the process is humbling. It’s an honor to have the opportunity to pray in this way.

As they say inside the inipi, ‘from the doorway in, to the doorway out,’ it’s my hope you’ve gotten a richer, more valuable understanding of the heart of the inipi, the meaning behind it, and the process of a sweat lodge from even before the beginning and after the end. Because after all, Aho Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ, everything is related!

References

- The Sweat Lodge: the house of the stone people: Lakota lineage holder Paul GhostHorse gives us insight into the purifying ritual.. (n.d.) >The Free Library. (2014).

- Marks, L. F. M. (2007). Great mysteries: Native North American religions and participatory visions. ReVision, 29(3), 29+.

- Goldstein, D. (2019). All bathers are equal: Where washing becomes a state of mind. TLS. Times Literary Supplement, (6090-6091), 48.