Burma Cubensis Strain Overview

A mild, lucid magic mushroom strain from Southeast Asia. A great choice for beginners.

The Burma strain is considered one of the milder magic mushrooms — but it still packs a psychedelic punch in the realm of 2–3 grams of dried mushrooms.

Burma magic mushrooms are a good choice for psychonauts looking for a playful, sensational journey through the cosmos but don’t want the experience to be too overwhelming, either. This is an excellent “starter” mushroom.

Most users say that Burma mushrooms don’t create deeply philosophical or cerebral kinds of trips. Rather, a voyage with Burma mushrooms is euphoric and dreamy.

This strain was first collected in Burma, now Myanmar, by a student and sent to amateur mycologist John W. Allen. This sample was then isolated and proliferated through various hobbyists and expert mycologists. Today the Burma strain is widely available through most mainstream spore vendors.

Burma mushrooms tend to be fairly easy to grow, and it’s a strain that grows quickly; colonizing Burma mushrooms on substrate takes only a few days.

Like most mycelium, Burma strain mushrooms love high humidity and cool temperatures during cultivation. Still, Burma mushrooms are known to take off pretty quickly when it comes to incubation and colonization.

Related: Magic Mushroom Strain Guide

Burma Strain Specs

| Potency | Average 🍄 |

| Cultivation | Easy |

| Species | Psilocybe cubensis |

| Substrate Recommendation | Manure |

| Cost | $ |

| Sold By | Sporeslab, Spores 101, High Desert Spores, Mushroom Prints |

History of The Burma Strain

The Burma strain originates from Southeastern Asia in its namesake, Burma, a country between Thailand and India.

The Burma mushroom strain was said to be collected by a Thai student from buffalo dung found in a rice paddy. Stories suggest that the original Burma mushroom was collected from just outside of Yangon, then Rangoon, a border village between Thailand and Burma, now known as Myanmar.

The student gifted a sample of the mushroom to John W. Allen, a true mushroom pioneer that has been credited for discovering many Psilocybe mushrooms and bringing them to the West in the late 1990s.

It’s said Allen grew only one flush of the Burma mushrooms and propagated the original spores, proliferating them throughout the globe.

According to anecdotal commentary from John Allen himself, Burma strain spores and many other strain spores that are sold online today originated from Allen’s South East Asia discoveries and propagation.

Burma Potency & Psilocybin Content

Burma is pretty weak compared to strains like Tidal Wave, Fuzzy Balls, or Penis Envy. It’s also on the low end of the average compared to so-called “average” Psilocybe cubensis strains like Golden Teachers or Albino Treasure Coast.

A recent analysis performed by Oakland Hyphae in the Psilocybin Cup found the average potency of 3 samples of the Burma strain to be around 0.50% total tryptamine levels (measured as percent of dried weight). The strongest submission contained 0.63%.

For reference, the average Psilocybe cubensis strain falls somewhere between 0.50% and 0.90%.

A closely-related strain, the Albino Burma strain, was notably more potent — suggesting the possibility that Burma has the potential for much more too. In spring 2021, the Albino Burma strain submitted by Blackstar Mycology tested at 1.4% total tryptamines (psilocybin, psilocin, and a few others).

Burma Variations & Genetic Relatives

Burma strain shrooms overlap relative potency and growth patterns with other strains collected from tropical regions of Southeast Asia. A few examples include the Cambodian, Koh Samui, and Vietnam strains.

It’s also directly related to the Albino Burma, which is a leucistic (low-pigented) version.

Where to Buy Burma Spores

Although Burma mushrooms are said to have been collected only one time in the wild, Burma mushroom spores were well preserved and are now readily available across the globe.

Thanks to John Allen’s sample, Burma mushroom spores can be found online from many major mushroom spore retailers.

- If you live in the United States — Spores 101, Miracle Farms, or High Desert Spores

- If you live in Canada — Sporeslab, Spores 101, and Mushroom Prints

- If you live in Europe — The Magic Mushroom Shop

Related: How & Where to Buy Magic Mushroom Spores (Legally).

Similar Strains to Burma Shrooms

There are several magic mushroom strains that have similar qualities to Burma mushrooms that create dreamy, lucid hallucinations without the intense introspective experience.

Here are a few options if you’re looking for a silly-cybin high:

Lipa Yai

The Lipa Yai strain, also from Thailand, is known to be above average when it comes to potency, and like Burma strain mushrooms, it is easy to grow. Like Burma magic mushrooms, Lipa Yai grows well in humid environments and colonizes quickly.

Amazon Shrooms

Amazon Shrooms may be from a completely different continent, but they’re also notoriously easy to grow like the Burma strain. This strain colonizes quickly and is mold resistant.

They are much more potent than Burma mushrooms and produce very large specimens.

Pink Buffalo Mushrooms

The Pink Buffalo strain of mushrooms was also found in the South Pacific regions of Asia on the Bay of Bengal. According to folklore, the psychedelic Pink Buffalo shrooms were picked directly from the dung of a pink buffalo.

Like Burma mushrooms, they’re a strain of the species Psilocybe cubensis.

Koh Samui

Koh Samui shrooms come from the exotic island off of the Bay of Bengal coast of Thailand.

Like Burma mushrooms, Koh Samui is fast-growing, fairly easy to grow, and contaminant resistant. They’re also considered about average in terms of potency — though they’re a bit stronger than the Burma strain at about 0.70% total tryptamines on average.

Cambodian

Like the Burma mushroom, this strain comes from a humid climate in the southern Pacific. Named after the country where it was first collected, the Cambodian strain has an average potency and is easy to grow, just like Burma mushrooms.

It comes from the same classification species as Burma shrooms, Psilocybe cubensis, and has a similar high tryptamine content averaging around 1.2%.

How to Grow Burma Mushrooms

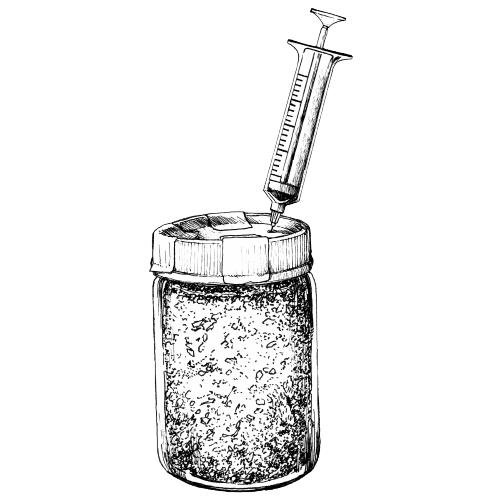

Like most psilocybin mushrooms, Burma mushrooms can be grown from spore prints or spores from a syringe directly on the substrate.

Burma mushrooms are considered easy to grow because they are resilient against mold and fast growing.

One of the most important aspects of growing mushrooms is keeping everything sterile. If you’re going to grow shrooms in your house, it could be easier to use a mushroom grow kit vs. setting up an entire sterile workspace or buying expensive equipment.

Try one of these top 5 mushrooms grow kits.

There are six basic steps to grow Burma mushrooms or any other species or strain of mushrooms.

Here’s a brief step-by-step guide to growing mushrooms:

1. Set Up the Substrate

The substrate is the material on which the mycelium —the body of the mushroom organism— grows.

Some mushroom strains prefer rye grain, while others prefer dung or wood chips for a substrate. Burma mushrooms tend to grow best on equine dung and enriched soils, but most Psilocybe cubensis strains grow just fine on rye grain, so don’t worry about using manure to grow your magic mushrooms.

Interestingly, the substrate is not just a ‘house’ for the body of the mycelium; it’s also a food source. This means you’ll need to add a form of nutrition to the substrate. Vermiculite is the go-to choice for feeding shrooms.

Mix rye grain, vermiculite, and water at a 2:2:1 ratio and put it in a sealable container. Fill the container almost to the top with the mixture, then top it off with another layer of vermiculite.

2. Sterilize

Heat the sealed container with the substrate in a pressure cooker for about a half hour at the steam sterilization and disinfection temperature of 121°C or 250°F.

3. Inoculate the Substrate

Once you’ve got a sterile substrate, you can apply Burma mushroom spore specimens or a syringe to fertilize the substrate with the mushroom strain. Work in a sterile space and reseal the container once you’ve inoculated it.

4. Incubate (Colonize)

This stage is a waiting game. With the substrate inoculated, now the mycelium network needs time to grow. Make sure the incubation space is humid, dark, and cool. Psilocybe cubensis thrive in high humidity, low light, and mild temperatures.

5. Fruit

Now that the mycelium has taken over and eaten the vermiculite, the substrate needs airflow. Make some holes or slits in your container. The air will penetrate, and the mycelium will begin to produce magic mushroom ‘fruits.’

6. Harvest Mushrooms & Let Them Dry

Burma mushrooms will produce tall, skinny brown or gold-capped fruiting bodies (mushrooms.) When they’re full size, harvest them by separating the stem from the substrate. Let them dry out in a cool space, and store shrooms until you’re ready for interplanetary takeoff!

If you’re serious about growing shrooms, gather a few extra pointers about growing magic mushrooms the easy way before you start.

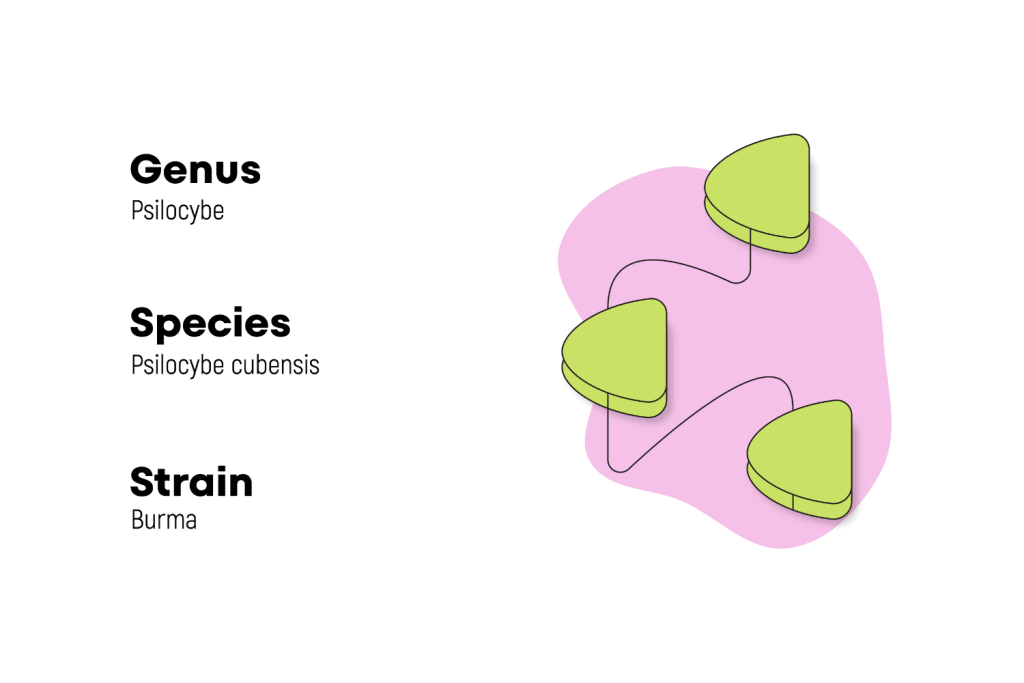

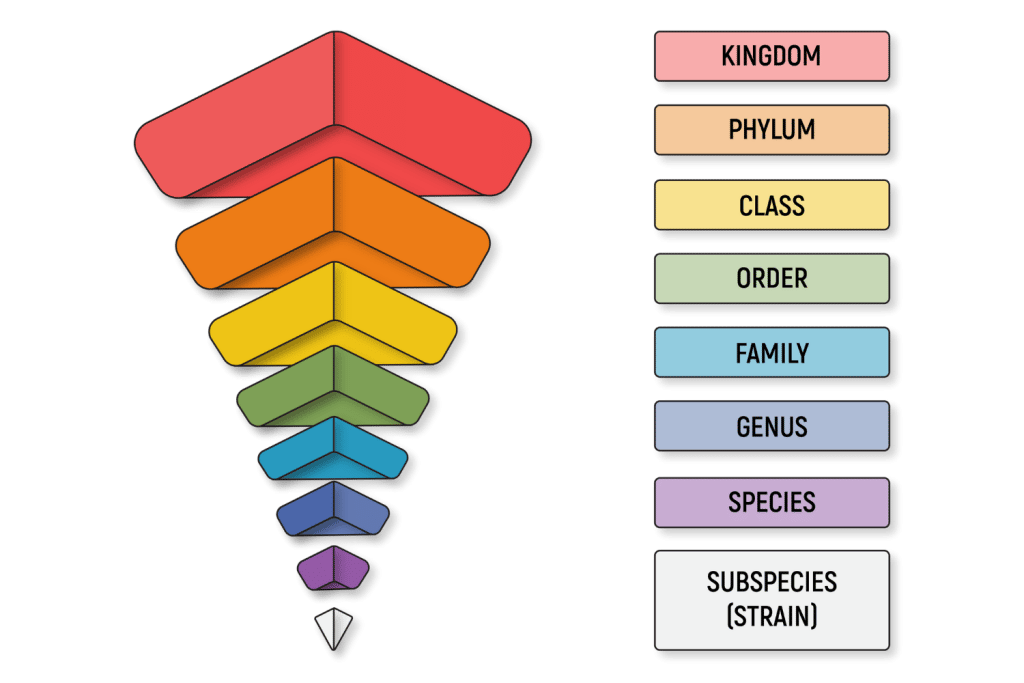

Strains vs. Species: What’s The Difference?

Strains and species are two different classifications used to describe organisms and plants.

Species are groups of similar organisms within a genus and have biochemical, phenotypic, or DNA relatedness. Conversely, strains are classified based on overall genetic similarity [2].

Species are a more all-encompassing classification than strains. They describe organisms that share the same genetic makeup. A species is a biological group that can reproduce to create fertile offspring that can also go on to reproduce.

Strains are a more specific classification. Strains are considered to be subtypes of a species that represent a particular genetic variation. When strains are pollinated, they reproduce fertile offspring that share the same genetics.

Understanding Strains & Species

This point can be illustrated by comparing species and strain classification systems to other living organisms.

Almost all domesticated pet dogs come from the Canis familiaris species. However, within this species, we know there are at least 200 genetic variations of the species. Although for dogs, these species subtypes (genetic variants) are called breeds, the concept applies in the same way to mushroom subtypes, called strains.

Species, thus, are an umbrella term to describe a particular category of an organism, as with psychoactive mushrooms, the Psilocybe cubensis species. Within this species of psychedelic mushrooms, the shrooms can be cultivated for specific variations, called strains, like the Burma strain, Penis Envy, Yeti strain, etc.

Scientists, mycologists, mushroom lovers, and psychonauts are constantly cross-cultivating strains to develop unique genetic variations or hone in on particular attributes of certain mushroom types.

Specific strains are usually cultivated because they produce particular desirable features. In the case of dog breeds (strains) certain dogs perform particular actions, have a particular disposition, or a particular coloring. In the case of mushroom strains, they may be cultivated for a particular psychedelic quality, growth pattern, or appearance.

Many psychedelic mushrooms are explicitly cultivated for their intense visual hallucination-inducing properties, which can be elementary to complex [3]. On the other hand, some psychedelic mushrooms are cultivated because they do not induce intense visual hallucinations but have powerful introspective effects. It’s up to the individual psychedelic explorer to determine which type of strain appeals to their unique needs in the astral realm.

If you’re new to psychedelics, you may want to start with gentler strains that will not send you to the other side of the universe to get a feel for psychedelic travels.

If you’re an experienced psychonaut, you could enjoy a strain that is above average in potency and contains high quantities of psilocybin or psilocin.

Reference

- Rodríguez Arce, José Manuel, and Michael James Winkelman. “Psychedelics, Sociality, and Human Evolution.” Frontiers in psychology vol. 12 729425. 29 Sep. 2021.

- Baron EJ. Classification. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 3.

- Teeple, Ryan C et al. “Visual hallucinations: differential diagnosis and treatment.” Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry vol. 11,1 (2009): 26-32.