Shroom Science: Understanding the Differences Between Psilocybin & Psilocin

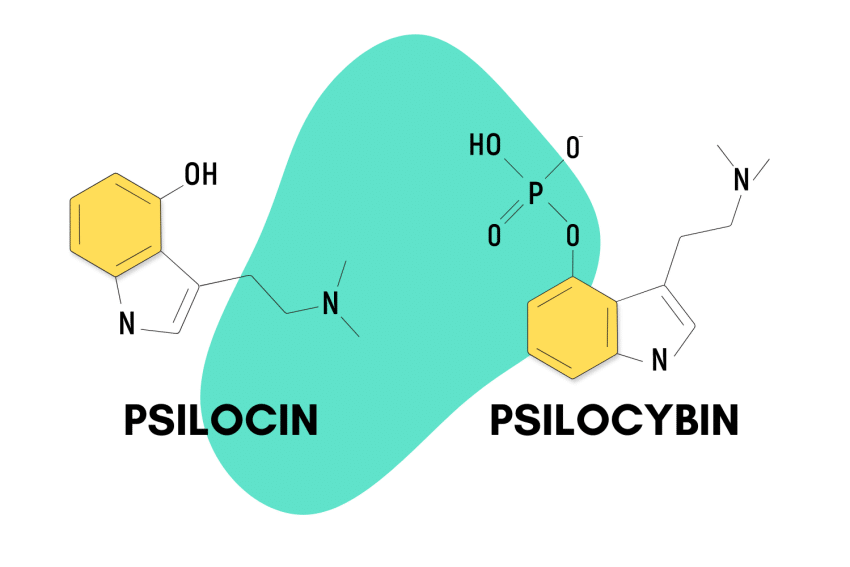

Psilocybin is the alkaloid most people associate with magic mushrooms, but it’s not hallucinogenic on its own — psilocin actually holds this honor 💪

Psilocybin and psilocin are the two most important alkaloids — organic compounds that affect humans — in magic mushrooms.

Most people associate mushrooms with psilocybin, but on its own, this molecule doesn’t cause any changes in perception. Psilocin is actually responsible for the subjective “trippy” effects.

The fruiting bodies of mushrooms contain only trace amounts of the tragically unstable psilocin.

How, then, are mushrooms reliably hallucinogenic?

We’ll compare and contrast the differences and similarities between these two compounds and how they work together to achieve the magic in these otherwise unassuming little brown mushrooms.

Psilocybin vs. Psilocin Comparison

| Psilocybin | Psilocin | |

| Chemical Name | O-phosphoryl-4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (4-PO-HO-DMT) | 4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (4-HO-DMT) |

| Psychoactive? | No | Yes |

| Average Concentration in Magic Mushrooms | 0.6 – 1.8% by weight, depending on the species | 0.1 – 0.5% by weight, depending on the species |

| Half-Life | 160 minutes | 50 minutes |

| Threshold Dose | 10 mg | 5 mg |

| Legality | Illegal | Illegal |

| Boiling Point | 739°F (392.8°C) | 974.2°F (523.4°C) |

| Molecular Weight | 204.27 g/mol | 284.25 g/mol |

Main Differences & Similarities: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

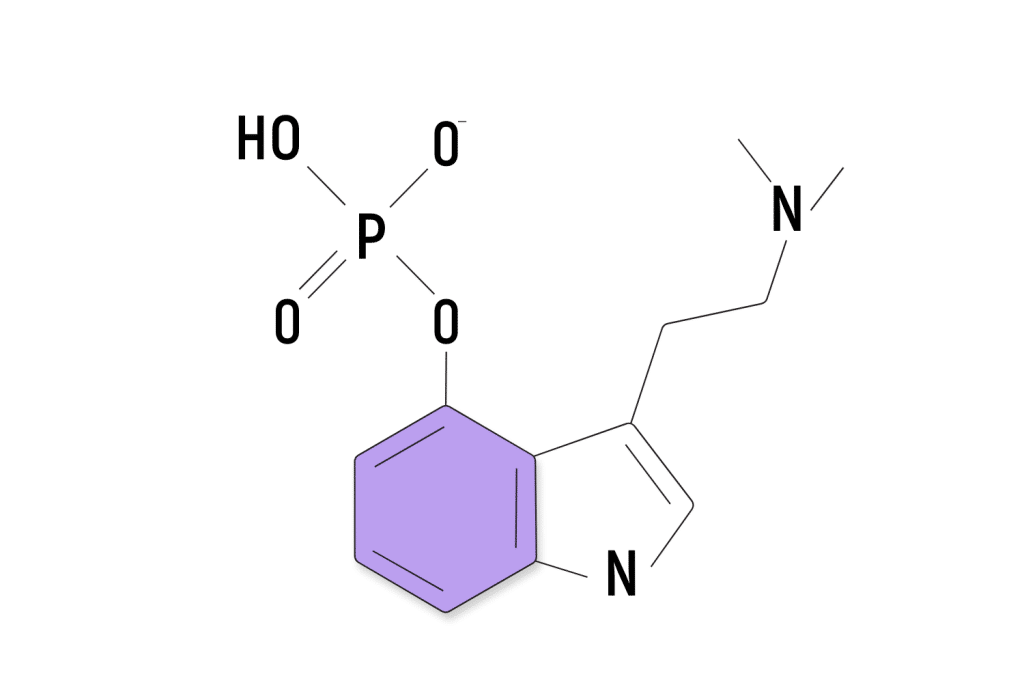

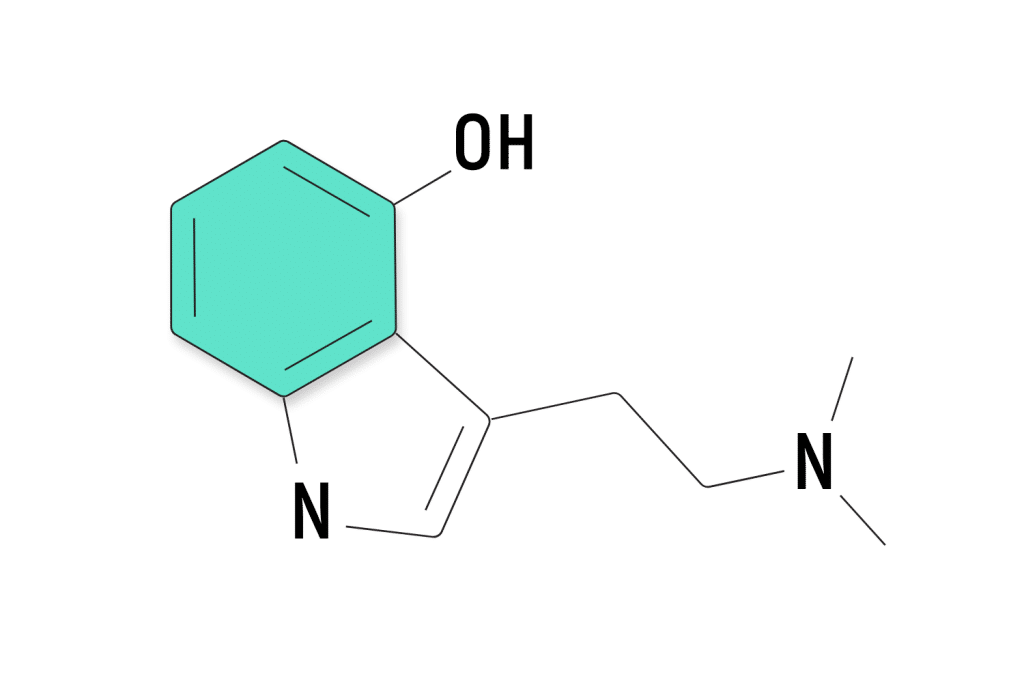

Psilocybin (O-phosphoryl-4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a pro-drug — or a substance we metabolize into a similar drug after we consume it. This metabolite, psilocin (4-hydroxy-dimethyltryptamine,) also occurs naturally in the mushroom in trace quantities [1].

Psilocybin helps stabilize the potency of magic mushrooms. As Alexander Shulgin put it in his book Tryptamines I Have Known and Loved (TiKHAL):

The older samples [of dried mushrooms] may be reasonably free of the rather unstable psilocin, but psilocybin is much more stable and may persist [2].

Prior to this, he spoke of taking the pure chemical forms of psilocybin and psilocin. Unlike other subjective reports, he found them to be “completely interchangeable as to their pharmacological properties.”

With the only difference being stability, scientists often create isolated forms of psilocybin as opposed to psilocin, so their product doesn’t go bad on the shelf after a short time.

Mushroom Potency: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

Psilocybin is the primary alkaloid in psychedelic mushrooms; this is the namesake of the genus classification Psilocybe, which many of them share. Psilocin occurs in trace amounts as well, but due to instability, it often degrades.

The content of each of these compounds varies from mushroom to mushroom. Here is a breakdown of the most common species of magic mushrooms:

Importantly, testing isn’t always reliable as the concentrations can vary from mushroom to mushroom. Growing conditions, time of year, and several other variables contribute to this uncertainty.

Then there’s the issue of psilocin degrading over time, meaning concentrations fluctuate daily. Researchers recently confirmed the relationship between the magic mushroom’s famous blue color and this factor [3].

Physical injury causes enzymes to oxidize the molecule and remove the phosphate group, converting it to psilocin. This less-stable compound dies off, causing a cascading effect and leaving the mushroom with a blue or indigo bruise [3].

As a result, bruising and physical trauma to the mushroom seems to slightly lower its potency, but this is not conclusive.

At any rate, even mushrooms with heavy bruising still seem to be plenty potent.

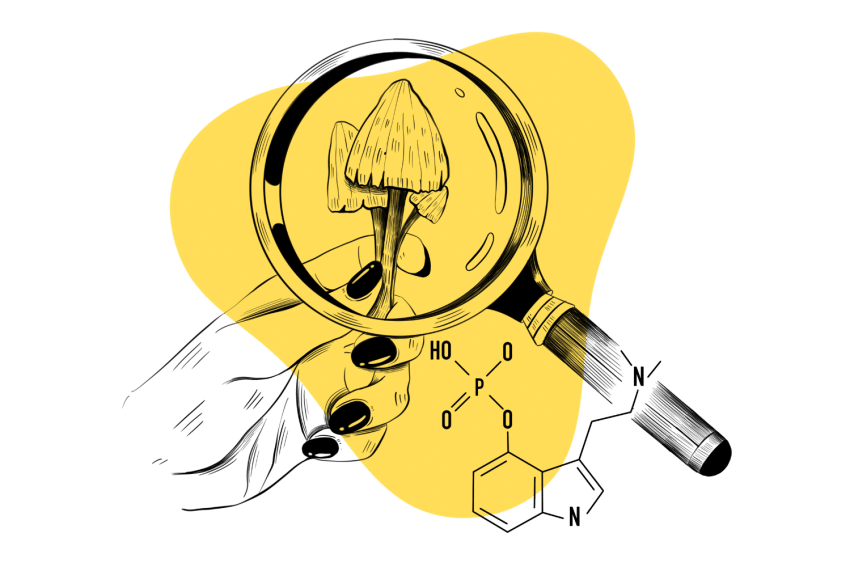

Chemical Structure: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

PubChem describes psilocin as “a tryptamine alkaloid that is N,N-dimethyltryptamine carrying an additional hydroxyl substitute.” Psilocybin contains the entire psilocin molecule and a phosphoryloxy group which converts to the hydroxy substitute after metabolism.

These extra chemical groups are enough to render psilocybin inactive and protect psilocin protected from MAO enzymes, respectively. One of the most exciting things about the psilocin molecule is that it’s an orally active form of DMT.

While the effects of psilocin vary drastically from DMT, the full DMT molecule exists within psilocin. Oral activity of DMT is normally impossible, but thanks to the hydrogen bond pulling the two ends together, psilocin differentiates itself [4].

While research is still preliminary, it seems likely this also enables psilocin to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and interact with serotonin receptors in the brain.

Pharmacology: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

The two most significant pharmacological differences between psilocybin and psilocin lie in their access to our brains and resistance to degradation. Psilocybin degrades slower but cannot cross over into the brain and communicate with neurotransmitters.

After conversion, psilocin can cross the tight grouping of cells blocking access to polarized compounds in the brain — or the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [5]. The system exists as a way to prevent unwanted chemicals from entering the precious organ while allowing others.

While the mechanism behind this is still uncertain, researchers suggest the bond masks the polar groups of the molecule [6]. Polarization may be a big excluding criterion for the BBB, so this may hide the polarity of psilocin.

This hydrogen bond also forms a barrier to protect the psilocin molecule from enzymes that would usually break it down. It is the stability of the phosphoryloxy arm on psilocybin that brings resistance to degradation outside of the body, however.

These two molecules showcase how big of a difference a slight change in structure can make. Psilocybin contains all of the psilocin molecules, but its slight addition removes the entire trip.

Psilocin contains the entire DMT molecule within it, but its slight difference brings on drastically different effects as well as the pharmacological benefit of oral activity.

Risks & Safety: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

When it comes to psilocybin, the median lethal dose for half the population (LD50) is 280 milligrams per kilogram of body weight (mg/kgbw), according to the Merck Index [7]. While there is no known LD50 for psilocin, it may be as low as 140 mg/kg based on the comparison of threshold doses.

However, this amount was for the LD50 of mice; it would translate to needing over 19,000 mg — or 19 grams — of psilocybin. Even if we used a heroic dose of 50 mg psilocybin as a basis for the ratio, it would still be 1:380.

Even cutting this number in half to account for the psilocin potency difference, 1:190 is an exceptionally safe ratio for any substance. Even alcohol can’t compete with a safety profile like that.

This doesn’t eliminate any risk of complications, however. The main concern with adverse reactions to psychedelics centers around the potential for mental harm.

Some theorize a psychedelic experience could trigger a mental health episode in people with an underlying psychiatric condition. Still, a negative experience with psychedelics can be traumatic for anyone.

Additionally, some anecdotal evidence suggests psilocin can have particularly bad effects on motor function. This can bring on a potential for physical danger if in an unsafe setting.

Dosage: Psilocybin vs. Psilocin

Whether you’re dealing with pure psilocybin or dried mushrooms, the dosage is critical. Psychedelics feel very different at each incremental step up in potency — always start with a low amount and build your way up to higher levels over time.

In this vein, there are five main groups psychonauts like to explore. These include:

Low Dose

10–15 mg psilocybin, 5–7.5 mg psilocin

At this level, the effects start to show, like brighter colors or a better mood. Light hallucinations or swirling patterns may also be possible, though not pronounced.

Sometimes called a “museum” dose since it boosts mood without being overwhelming, this is a nice, light entry into psychedelics. We recommend taking at least two weeks between doses of this size to give your tolerance time to reset.

With low doses, the two substances are likely identical, except for psilocin having a shorter duration and come-up period.

Medium Dose

17–35 mg psilocybin, 7.5–17.5 mg psilocin

At this level, expect moderate effects and undeniable perceptual changes. Open- and closed-eye visuals are likely, and the effects are obvious — especially at the higher end of this amount.

This is where psilocin begins to have the potential to differentiate itself from psilocybin. Users often report psilocin as having a heavier visual element and stronger hallucinatory sensation, which would start to take effect here.

Bear in mind, the difference between the low and high ends of this range is more than enough to alter the experience dramatically. Though tolerance builds quickly with psilocybin, you can expect a reset at this level within a month at the longest.

Heavy Dose

35–50 mg psilocybin, 17.5–25 mg psilocin

This is a full-blown psychedelic experience with heavy distortions of perception and critical thinking. Experiences are highly dependent on the user but expect to buckle up for this journey.

Subjective reports state psilocin is more likely to lead to poor motor function and an inability to move at this level as well. While this is possible with psilocybin, many people suggest psilocin has a stronger body sensation, perhaps due to its quicker onset.

At this level, we’d recommend getting a trip sitter or a sober friend to be on standby. You can’t expect to handle yourself rationally at this level, and it’s always best to have a safeguard in place.

We recommend taking this amount less than four times a year.

Heroic Dose

50 mg+ psilocybin, 25 mg+ psilocin

Terence McKenna is responsible for coining the term “heroic dose.” He said he felt he was “hitting it pretty hard” if he took more than 2–3 doses of this size a year. In his mind, this dosage in a dark room with no sound was the ideal way to consume psychedelics.

There is not enough information to know if psilocin would act differently from psilocybin at this level, but it’s likely the user would be unable to move or articulate any differences anyway.

Here’s what McKenna had to say when answering questions about how to take mushrooms and what dose is appropriate:

It’s easy to tell you how to do it, and it’s amazing how few people do it right. You do it in darkness, on an empty stomach, in silence, alone… Most people who take mushrooms and claim knowledge of what mushrooms are all about are talking about the 2–3 gram level. The game doesn’t begin until you reach five grams.

Acknowledging this is a high dosage, he added, “It can’t kill you; it can only convince you that it can kill you.”

Summary: How Is Psilocin Different from Psilocybin?

In many ways, it makes sense to lump psilocybin and psilocin together. Though psilocin is the compound that makes the mushroom so magical, it wouldn’t exist in reliable amounts without psilocybin.

Whenever you consider taking a substance of any kind — let alone one as profound as this — it’s important to learn everything you can about it. Research any potential risks, benefits, or concerns associated with every drug you take.

Understanding the relationship between these two molecules is crucial for respecting the way they operate. Knowledge is the best ally in the war against a bad trip.

The vital function of both only contributes to the mysticism of the mushroom and its relationship with us. Not only did it conjure up an alkaloid capable of introspective power unlike almost anything else on the planet, but it also did so with a failsafe to ensure it was reliable.

Frequently Asked Questions About Psilocybin & Psilocin

Here are some of the common questions people ask about these magic compounds:

1. Is Psilocybin Psychedelic?

Technically, no. Psilocybin is a non-psychedelic compound our bodies rapidly metabolize into psilocin. Psilocin — which also occurs in the mushroom in small quantities — is the molecule responsible for the effects of magic mushrooms.

2. Why Did Fungi Evolve to Create Psilocybin & Psilocin?

Some believe fungi began creating these compounds as a way to deter animals and insects from eating them. Others think it is the opposite — that by getting more people and animals to eat and then pass them, mushrooms are more effectively spreading their spores throughout the world.

We aren’t fully certain of the correct answer since psilocybin-containing mushrooms predate modern humanity. One researcher suggests the consumption of mushrooms by human ancestors may date back as far as 5.3 million years ago [8].

If this is true, humanity (or some early form of it) was consuming mushrooms for a full 5 million years before homo sapiens would appear.

3. Why is Pure Psilocin Rare?

Psilocin is infamously unstable. When looking at dried mushrooms, you can see this in the blue bruises, which represent a loss of the molecule.

Psilocybin, on the other hand, has a much more reliable shelf-life and readily metabolizes into psilocin. As a result, most research takes place using psilocybin to ensure potency and purity.

4. Are There Any Studies on the Difference Between Psilocin & Psilocybin?

Currently, no. One is underway, however, to test the difference between a couple of different modes of ingestion for psilocin against psilocybin.

The findings of this study may have a heavy impact on the standard protocols for research on psilocybin.

Some of the things they’re looking for are:

- Reliability — Will psilocin act more reliably across various patients with the variable factor of their metabolism out of the equation?

- Duration — Longer duration isn’t always better. If psilocin can act for a shorter time and produce similar effects, it may be less expensive for therapeutic use.

- Effects — Each participant will blindly try both molecules so they can compare the two.

Results from this breakthrough study likely won’t be ready until late 2024, but it’s exciting nonetheless.

5. How Do You Safely Take Psilocybin & Psilocin?

Many of the risks associated with a “bad trip” are easy to mitigate with preparation and precaution.

If you’re planning to experiment with psilocybin or psilocin, make sure to follow the safety guidelines below:

- Respect — Understand the importance of psychedelics, the potential they have, and the impact they’ve made on the world.

- Know the Law — You should know whether the substance is legal in your area.

- Dosage — Start with a low dose and slowly build up over time.

- Don’t Mix — Don’t take psychedelics with medication, particularly heart, neurological, or psychiatric medications.

- Set and Setting — You should have cozy surroundings and a healthy, open mindset.

- Tripsitter — Either in person or easily accessible, make sure there’s a sober, responsible person you can call on for assistance.

- Timeline — Familiarize yourself with the timeline of your journey. On average, expect to wait for an hour or more for the onset and a return to baseline after 6–8 hrs.

- Know When to Avoid — If you have underlying heart, neurological, or psychiatric disorders, you should not consume psychedelics.

While it’s not possible to ensure a bad trip never happens, these practices should greatly help in avoiding one. If you find yourself facing negative thoughts or hallucinations, try to remain open and calm. Most bad thoughts and feelings go away after you acknowledge them.

References

- Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2017). Metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin: clinical and forensic toxicological relevance. Drug metabolism reviews, 49(1), 84-91.

- Shulgin, A. T., & Shulgin, A. (1997). TIHKAL: the continuation (Vol. 546). Berkeley: Transform press.

- Lenz, C., Wick, J., Braga, D., García‐Altares, M., Lackner, G., Hertweck, C., … & Hoffmeister, D. (2020). Injury‐triggered blueing reactions of Psilocybe “magic” mushrooms. Angewandte Chemie, 132(4), 1466-1470.

- Migliaccio, G. P., Shieh, T. L. N., Byrn, S. R., Hathaway, B. A., & Nichols, D. E. (1981). Comparison of solution conformational preferences for the hallucinogens bufotenin and psilocin using 360-MHz proton NMR spectroscopy. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 24(2), 206-209.

- Hindle, S. J., & Bainton, R. J. (2014). Barrier mechanisms in the Drosophila blood-brain barrier. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, 414.

- Lenz, C., Dörner, S., Trottmann, F., Hertweck, C., Sherwood, A., & Hoffmeister, D. (2022). Assessment of Bioactivity‐Modulating Pseudo‐Ring Formation in Psilocin and Related Tryptamines. ChemBioChem.

- Windholz, M., Budavari, S., Stroumtsos, L. Y., & Fertig, M. N. (1976). The Merck index. An encyclopedia of chemicals and drugs (No. 9th edition). Merck & Co.

- Rodríguez Arce, J. M., & Winkelman, M. J. (2021). Psychedelics, sociality, and human evolution. Frontiers in Psychology, 4333.