How to Make Ayahuasca: Step-by-Step Guide

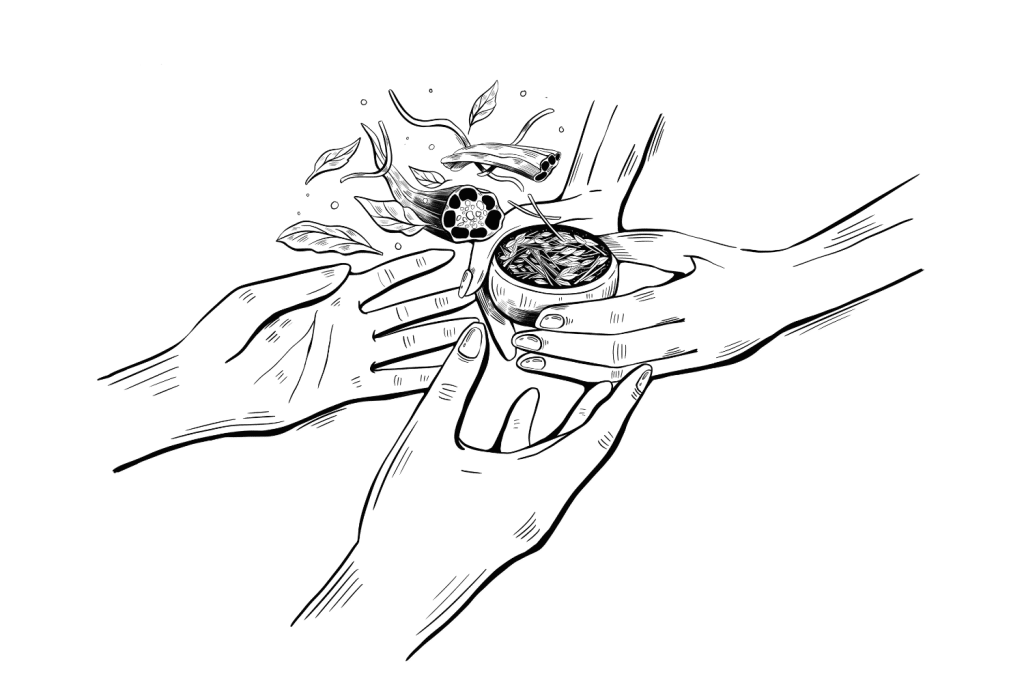

The traditional method of brewing ayahuasca involves decocting (boiling) the ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) and chacruna (Psychotria viridis) together for several hours.

After several hours of boiling, you’re left with the thick, bitter liquid that is ayahuasca.

While it’s best to leave ayahuasca production up to the professionals, it’s relatively simple to make at home.

Ayahuasca basically consists of three parts:

- A Source of DMT — Located throughout nature, many plants naturally contain DMT. Knowing which ones to choose and how much to use is the trick.

- A Source of Monoamine Oxidase Enzyme Inhibitors (MAOIs) — MAOs exist throughout nature, but the most common sources are the ayahuasca vine and Syrian rue.

- Water — water is used as the solvent to extract the active ingredients from both plants.

Once you’ve gathered your ingredients, you’ll need to understand how to put them together without destroying any of the crucial components.

Here, we’ll cover two recipes for ayahuasca (one traditional and another that’s more accessible outside of South America). We’ll also explain how the brew works and answer some common questions about ayahuasca.

Ayahuasca Ingredients

The basic recipe for ayahuasca is [DMT] + [Harmala alkaloids].

The brew is made by mixing these plants together and gently boiling them in water for several hours — topping them up with more plant material and water when the water level starts to get low.

Let’s take a closer look at the individual components and what options are available.

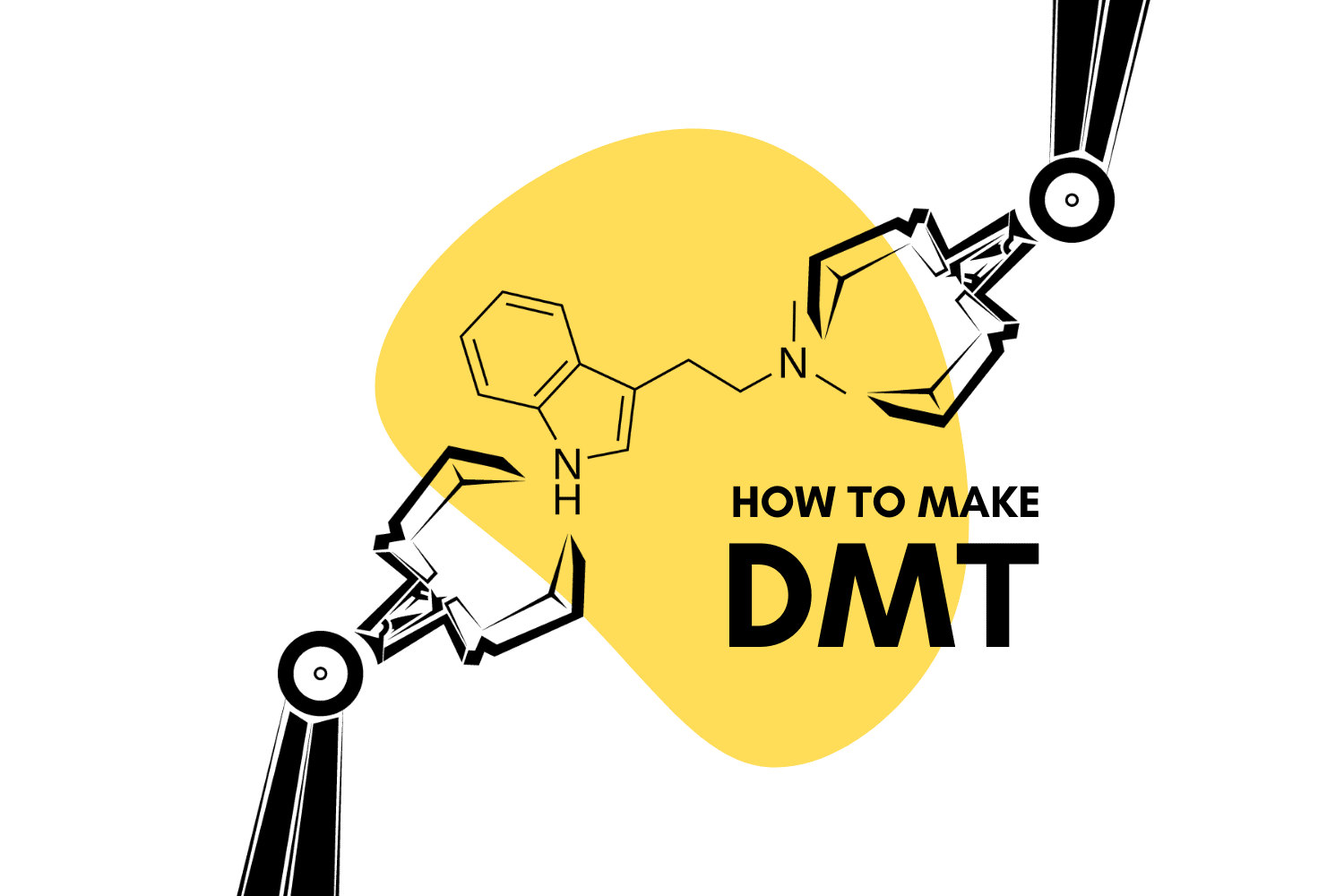

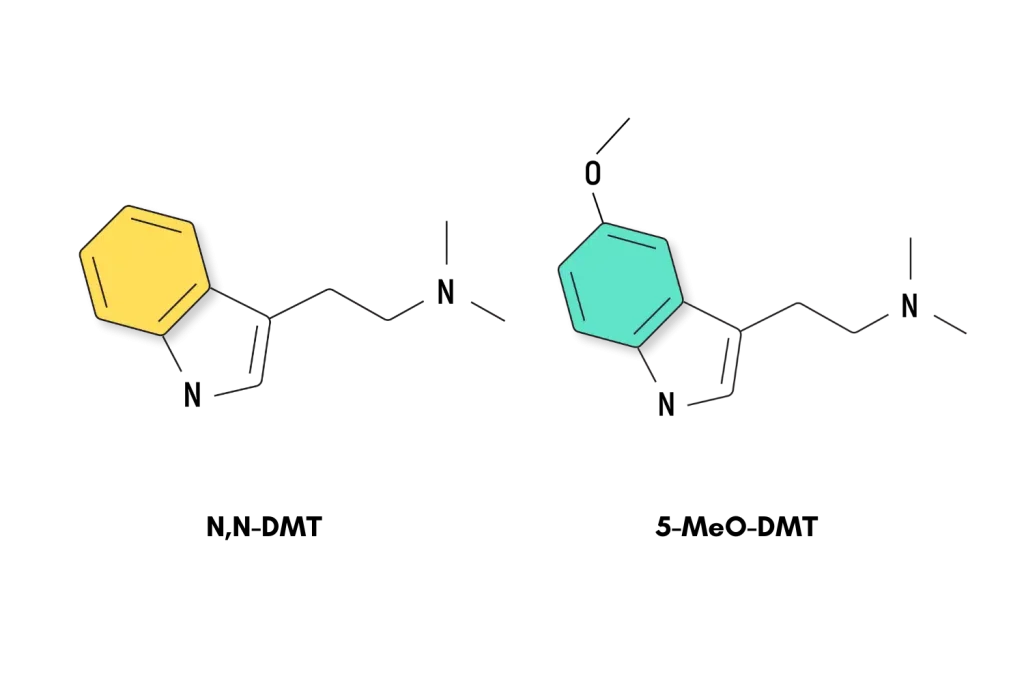

1. A Source of DMT (Dimethyltryptamine)

The most common source of DMT (dimethyltryptamine) used in traditional ayahuasca is either chacruna (Psychotria viridis) or mimosa (Mimosa hostilis) — but many other plants can be used too.

DMT is surprisingly common in nature [2] — even in a few innocuous locations such as acacia trees or common reeds.

What is DMT?

In addition to the places in nature where you can find DMT, many also believe it to be produced in very small quantities in the human body [3]. While scientists are not yet sure why DMT is in the body, some common theories are that it induces consciousness at birth, transitions us to the afterlife at death, or generates dreams.

Taken as a drug, DMT is one of the strongest psychedelics in the world, if not the strongest.

What Does DMT Do?

Most people take pure DMT by either smoking it or vaping it. DMT is not active orally without the presence of an MAO inhibitor.

This compound produces strong out-of-body effects and other-worldly experiences and is used to explore the mind and the self. Traditionally, it was used for healing the soul, obtaining information from beyond the physical world, or as a tool for divination.

The effects of smoking DMT last only around 15–30 minutes, but many people experience time-dilation — the experience feels like it lasts much longer than it actually does.

Plants That Contain DMT

As we noted above, DMT is readily available throughout nature and in trace amounts in the body, but it can also be made synthetically.

Some notable plants that contain DMT include:

- Psychotria viridis — This is the most common plant ayahuasqueros use to make ayahuasca. This plant contains around 0.6% N,N,DMT by dried weight. In Ecuador, the related plant, Psychotria carthaginensis, is typically used instead.

- Mimosa hostillis — A bushy tree containing 1% DMT in the bark — which puts it on par with Psychotria viridis. This plant is typically the favorite of anyone looking to make ayahuasca or DMT at home because it’s widely available and easy to grow outside the Amazon rainforest.

- Anadenanthera peregrina (Yopo) — The seeds of this tree contain N,N,DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, and bufotenine. Historically, cultures would roast, crush, and snort these seeds for their effect.

- Acacias — Various species of this genus contain levels of DMT ranging from 1-2%.

2. A Source of MAO Inhibitors (Harmala Alkaloids)

The most common source of MAO inhibitors in nature is a group of indole alkaloids called the “harmala alkaloids” [5]. This includes harmaline, harmine, harmalol, and tetrahydroharmine.

There are also synthetic MAO inhibitors. A preparation called pharmahuasca uses these pharmaceutical MAO inhibitors, and either synthetic DMT or DMT-rich plant extracts to produce a similar ayahuasca experience.

What Do MAO Inhibitors Do?

MAO inhibitors bind to monoamine oxidase and prevent it from doing its job — breaking down monoamine neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and, of course, DMT.

By temporarily blocking this enzyme, DMT is absorbed into the bloodstream and travels to the brain, where it exerts its effects. Once the MAO inhibitors wear off, the DMT is broken down and deactivated.

Doctors prescribe pharmaceutical monoamine oxidase inhibitors for treatment-resistant depression. The idea is that by blocking this enzyme, the drug causes an increase in serotonin. Unfortunately, these strong pharmaceutical MAOIs have a long list of side effects.

Even in ayahuasca, the MAO inhibitor causes the purging that is characteristic of the experience.

This purging is viewed as an important part of the healing process.

What Plants Contain MAOIs?

Harmala alkaloids are less abundant than DMT in nature, but there are a few notable sources that can be used to make ayahuasca:

Some examples of plants that include harmala alkaloids (MAO inhibitors) [6]:

- Ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) — The ayahuasca vine contains three main harmala alkaloids, harmine, tetrahydroharmine, and harmaline.

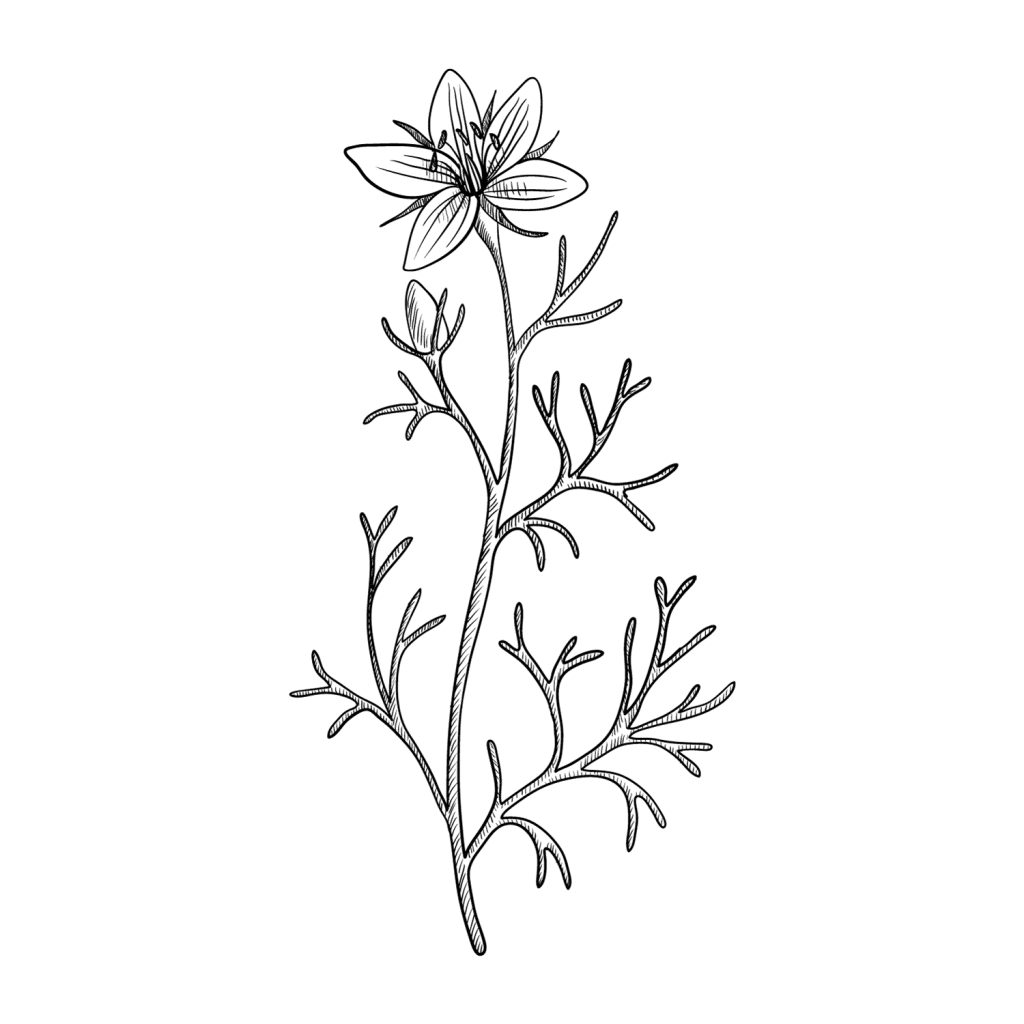

- Syrian Rue (Peganum harmala) — This plant has a long history of use as an MAOI in the Middle East and Asia. Some have used these seeds to “ward off evil spirits,” as a potent red dye, or as an MAOI.

- Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata) — This beautiful flower contains over 600 species of tropical plants. These are mostly in South and Central America and have a history of indigenous use for potentiating DMT, psilocybin, and others.

- Ginkgo biloba: Though less well-known or used, ginkgo contains carbolines with MAOI activity.

What Else is Monamine Oxidase Used For?

It’s important to understand that monoamine oxidase enzymes are an important part of every person’s digestive system, in addition to metabolizing DMT.

In addition to DMT, the monamine oxidase enzyme breaks down the following neurotransmitters [7]:

- Norepinephrine — This is the chemical responsible for your “fight or flight” reflexes. High levels left by the resistance to degradation may lead to an elevated heart rate.

- Serotonin — A complex and vital neurotransmitter within the brain. Too much serotonin, however, can lead to the hazardous condition of “serotonin syndrome.” This condition causes fever, chills, diarrhea, muscle rigidity, seizures, and even death if not treated.

- Dopamine — This is the “feel good” chemical, and the resistance to it breaking down is likely a large part of the mechanism of action for the antidepressant effects of MAOIs.

All of these transmitters go into the antidepressant effects of MAOIs. The elevated norepinephrine raises the heart rate and mood a bit, along with increasing the two chemicals responsible for happiness — serotonin and dopamine.

The main problem comes from a compound called tyramine. This neurotransmitter helps control blood pressure; eating foods like cheese or cured meats that are high in tyramine and block the enzyme that breaks it down can cause problems.

This is part of the reason why it’s important to follow dietary restrictions for a few weeks while preparing for an ayahuasca session.

Recipe #1: How to Make Ayahuasca Using Syrian Rue

Syrian rue is a better source of harmala alkaloids for people living outside the Amazon rainforest. The ayahuasca vine only grows in the rainforest, and overharvesting for export is already becoming a major problem. On the other hand, Syrian rue can be grown just about anywhere and is therefore readily available.

For Syrian rue-based ayahuasca, mix the seeds of the plant with either Mimosa hostilis, Psychotria viridis, or another plant that contains DMT. Gently boil the mixture in water, reducing it by about half.

You can avoid the boiling process by crushing the seeds and swallowing them with a bit of water. Follow this about 20 minutes later with tea or capsules containing a DMT-rich plant.

To make this direct ayahuasca analog, you’ll need the following ingredients:

- 3–4 g Syrian rue seeds It’s important to note that there is no benefit in going over this amount; in fact, doing so may cause the trip to have unpleasant side effects.

- 25 g Psychotria viridis leaves. You will need to dry and crush these if you have them fresh.

- One lemon, juiced.

- Water. Just enough to boil it all together.

Once you have your ingredients, here’s a recipe for brewing ayahuasca using Syrian rue:

- Place all ingredients together in a small pot.

- Bring the pot to a boil, then reduce the heat to simmer for about five minutes.

- Strain the material from the liquid and add it to a fresh pot of water to repeat the process two more times.

- Strain and discard the plant material.

- Place all three extracts together and carefully heat the mixture to a slow boil until you’re left with half the amount of liquid you started with.

- After boiling your concoction down to the desired level, let it cool. Refrigerate until ready to use.

The lower the water level you’re left with, the worse the flavor will be (but the flavor is never very good). For this reason, many choose to boil the water down to about the level of a shot glass. This concoction will taste horrible, but it’s over quickly.

Take this with a shot of grapefruit juice or something with a similar level of citrus and overpowering flavor.

Recipe #2: Traditional Ayahuasca Recipe

In his book, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants, Christian Rätsch documents the preparation methods of several cultures. Below is the recipe he wrote down for the Ecuadorian shamans:

The bark of the Banisteriopsis caapi liana is peeled off and placed beneath a certain tree in the forest. The bare stems are then split into four to six strips and boiled together with fresh or dried Psychotria viridis leaves. One dose is a piece of liana approximately 180 cm long with forty Psychotria leaves, although a piece of the stem just 40 cm long and 3 cm thick is also said to be sufficient. Generally, the less vine you use, the easier the ayahuasca is on the stomach [8].

Depending on the culture, the amount of water (and, therefore, the amount of time it takes to boil it down) differs greatly.

Some people add other plants and mixtures depending on what grows locally or what the shaman prefers to include. Sometimes they’re psychoactive too (such as datura); other times, they’re non-psychoactive but offer other healing benefits.

There truly is no one-size-fits-all approach to ayahuasca preparation.

Many will argue that anything other than a mixture of the caapi vine is not considered ayahuasca. I prefer a more inclusive use of the term that helps encourage the use of other MAOI sources.

Ayahuasca (The Brew) vs. Ayahuasca (The Vine)

When people refer to “ayahuasca,” they’re talking about the psychedelic brew, a combination of the ayahuasca vine mixed with another plant.

Ayahuasca the Vine

Banisteriopsis caapi is the vine many cultures refer to as “ayahuasca” — or “vine of souls” — on its own.

While this vine is a key ingredient in ayahuasca, it is not actually psychedelic on its own. It may have certain anti-depressive and neurogenic properties [1], but it won’t make you “trip.”

The active ingredients in the ayahuasca vine include harmine, tetrahydroharmine, and harmaline — all of which are potent monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Ayahuasca the Brew

The ayahuasca brew is a dark, thick, bitter liquid used to induce profound psychedelic visions. The main ingredient is the ayahuasca vine, but another plant is needed to produce the psychedelic effects. The vine serves to “activate” another plant that, on its own, is inactive.

It’s unclear how this brew was first created. Mixing two inactive plants doesn’t make much sense without knowing complex chemistry.

When you ask a shaman that works with ayahuasca (called an ayahuasquero), they will likely tell you that “the plants told” their ancestors how to prepare it.

Is it Important to Follow Traditional Recipes?

This depends on who you ask. Some argue that changing the ingredients changes the spirit of the journey. With the complexities surrounding the sacred plants, it seems hard to justify using the traditional ones when the result could be so catastrophic.

While all elements of the rainforest are complicated right now by the rapidly evolving problems of global warming, this one faces the additional challenge of increased interest. It’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are coming to understand the benefits of these plants, but it’s important to respect them and their place in nature.

As we’ve seen above, there is no singular recipe for “ayahuasca.” The spirit of the brew has always been centered around love and respect for nature. I’d argue that adjusting the plants we used based on what’s less harmful is right in line with that.

That’s not to say there is any issue with going the traditional route for an ayahuasca experience. Several choose to do this, which isn’t necessarily a problem, but we suggest you consider the options before pulling the trigger.

Why You Shouldn’t Make Ayahuasca At Home With Banisteriopsis Vine

While this is the traditional source found in shamanic rituals, it’s not the best from an ecological standpoint.

That isn’t to say it shouldn’t be a part of traditional ayahuasca ceremonies. Rather, we should leave it for those circumstances — especially when other options that work just as well are readily available.

Workers have to harvest the caapi vine from a living plant that’s at least five years old. Regardless of harvesting practices, it’s a recipe for disaster.

Mixing indigenous use with western interests means there may not be enough caapi to go around. That’s why some people choose to go with alternatives and allow the tools other cultures rely on to remain available.

As an alternative, use Syrian rue seeds, which grow abundantly in young plants. Harvesting the seeds from living plants is easy, and only 2–5 g are necessary, making this a more ecological option.

Not only that, but they’re extremely cost-effective to buy and easy to find online.

Making Ayahuasca at Home: Frequently Asked Questions

Making ayahuasca is complicated and leaves a lot of room for interpretation. Here are some of the questions people frequently wind up asking during the process.

1. Is Ayahuasca a Plant?

Ayahuasca is both the mixture of ingredients in the psychedelic brew and the colloquial term for the Banisteriopsis caapi vine. The latter is an ingredient in the former, which can make the term confusing.

On its own, ayahuasca from the vine is not intoxicating and acts only as an inhibitor of the MAO enzyme. Its crucial role in inhibiting this enzyme is why the DMT from the second source is orally active in the ayahuasca brew.

2. Why Isn’t DMT Orally-Active?

DMT isn’t active orally because of a digestive enzyme present in our digestive systems called monoamine oxidase. This enzyme immediately metabolizes and disables the effects of DMT [4].

This is why a substance that blocks the effects of this enzyme is essential for DMT to offer any psychedelic effects when consumed orally.

3. How do MAOIs Affect Tyramine?

Tyramine is a neurotransmitter that helps to regulate blood pressure. Excess tyramine in the system can lead to an elevated heart rate or, in extreme cases, a heart attack or failure.

When deciding to take an MAOI, follow a strict diet to reduce the amount of tyramine in your system. While the body creates the neurotransmitter on its own, it’s also abundantly found in the following foods:

- Alcohol — Especially beer and red wine

- Aged Cheeses

- Soybeans

- Smoked/processed meats

- Cured meats

- Spoiled and leftover food — Only eat fresh, non-processed food

It’s best to avoid these foods for at least 24 hours before you partake. If you’re planning to take ayahuasca in a traditional ceremony, they typically ask you to fast for at least as long.

In addition to giving your belly less food to throw up, this keeps you from any possibility of an adverse reaction from tyramine.

4. Is Ayahuasca Different When Made at Home?

Set and setting are essential elements of any psychedelic experience, so it likely will be different. It’s hard to see an experience from your couch equivalent to a ritual in the rainforest, but some argue a familiar environment is better.

While there may be a lot to gain from tripping in an unfamiliar environment surrounded by nature, it’s not where you live your everyday life. According to some, having the experience in your usual surroundings can make the change more profound.

Additionally, many indigenous cultures do not celebrate the tourism industry of ayahuasca ceremonies. The decision to attend one of these ceremonies or create one from the comfort of their home is up to each person.

There’s no reason to anticipate one to be inherently better or worse than the other. If you decide to trip at home, this expectation alone may be enough to influence the trip to fulfill it.

5. Is Ayahuasca Safe?

In discussing the safety of psychedelics, risk factors are split into two categories: physical and mental. Physical concerns about ayahuasca are rather slim, but the mental and emotional risks can be substantial.

With the inhibition of MAO enzymes comes a risk for heart problems, and you shouldn’t take ayahuasca if you have a history of these. Especially without careful consideration of diet, the increased levels of tyramine can send the heart rate spiking.

For most, this isn’t a big deal, but it can be deadly serious for anyone with underlying conditions. MAOIs may also interfere with other medications, particularly those that mimic or influence serotonin and dopamine.

Mentally, the risks mostly revolve around what can come from a bad trip. During an ayahuasca experience, frightening and dark visuals can pop up at any moment. In extreme cases, these can even be enough to leave users with PTSD.

Having a trip sitter nearby to help deal with any negative emotions that may arise is best practice. If you’re alone and find dark thoughts coming up, do your best to acknowledge them and face them head-on.

Users often find that doing so enables them to teach the lesson they’re there for and resolve the emotion or memory.

References

- Morales-García, J. A., De la Fuente Revenga, M., Alonso-Gil, S., Rodríguez-Franco, M. I., Feilding, A., Perez-Castillo, A., & Riba, J. (2017). The alkaloids of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of the Amazonian hallucinogen Ayahuasca, stimulate adult neurogenesis in vitro. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1-13.

- Carbonaro, T. M., & Gatch, M. B. (2016). Neuropharmacology of N, N-dimethyltryptamine. Brain research bulletin, 126, 74-88.

- Barker, S. A. (2018). N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an endogenous hallucinogen: Past, present, and future research to determine its role and function. Frontiers in neuroscience, 12, 536.

- Barker, S. A. (2018). N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an endogenous hallucinogen: Past, present, and future research to determine its role and function. Frontiers in neuroscience, 12, 536.

- Morales-García, J. A., De la Fuente Revenga, M., Alonso-Gil, S., Rodríguez-Franco, M. I., Feilding, A., Perez-Castillo, A., & Riba, J. (2017). The alkaloids of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of the Amazonian hallucinogen Ayahuasca, stimulate adult neurogenesis in vitro. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1-13.

- Chaurasiya, N. D., Leon, F., Muhammad, I., & Tekwani, B. L. (2022). Natural Products Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidases—Potential New Drug Leads for Neuroprotection, Neurological Disorders, and Neuroblastoma. Molecules, 27(13), 4297.

- Laban, T. S., & Saadabadi, A. (2022). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Rätsch, C. (2005). The encyclopedia of psychoactive plants: ethnopharmacology and its applications. Simon and Schuster.