List of All Common Dissociative Drugs & Their Effects

Dissociatives disconnect you from yourself and the world around you 👽🪐

What do ketamine, PCP, MXE, nitrous oxide, and DXM all have in common? They’re dissociative drugs — which means they have the capacity to dissolve one’s sense of self.

The dissociative experience is bizarre, blissful, and deeply therapeutic — when used with the right intention, context, and in strict moderation.

Long-term or irresponsible use of dissociatives has the complete opposite effect — often causing users to lose touch with themselves and their unconscious behavior. Some will even lead users to sustain serious cognitive damage.

Quick Jump: Common Dissociative Drugs

| Image | Drug Name | Drug Class |

| Dextromethorphan (DXM) | Opioid |

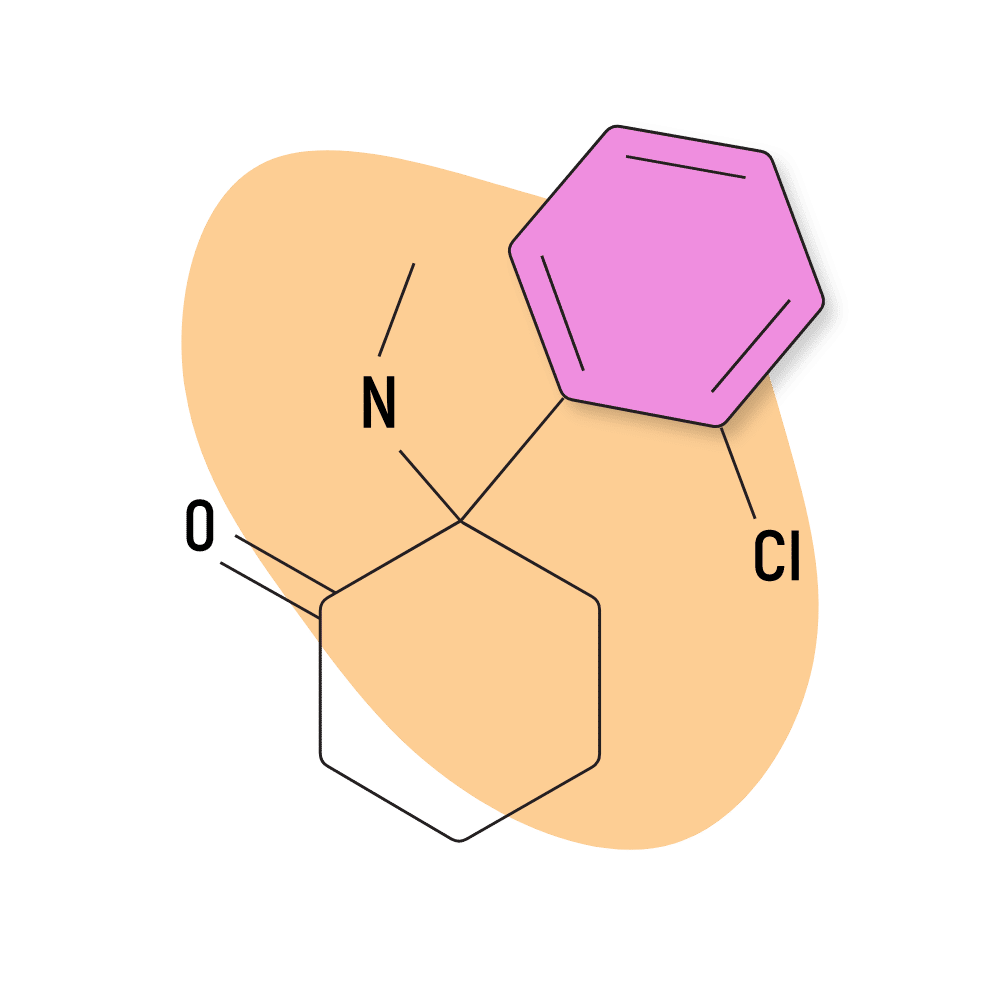

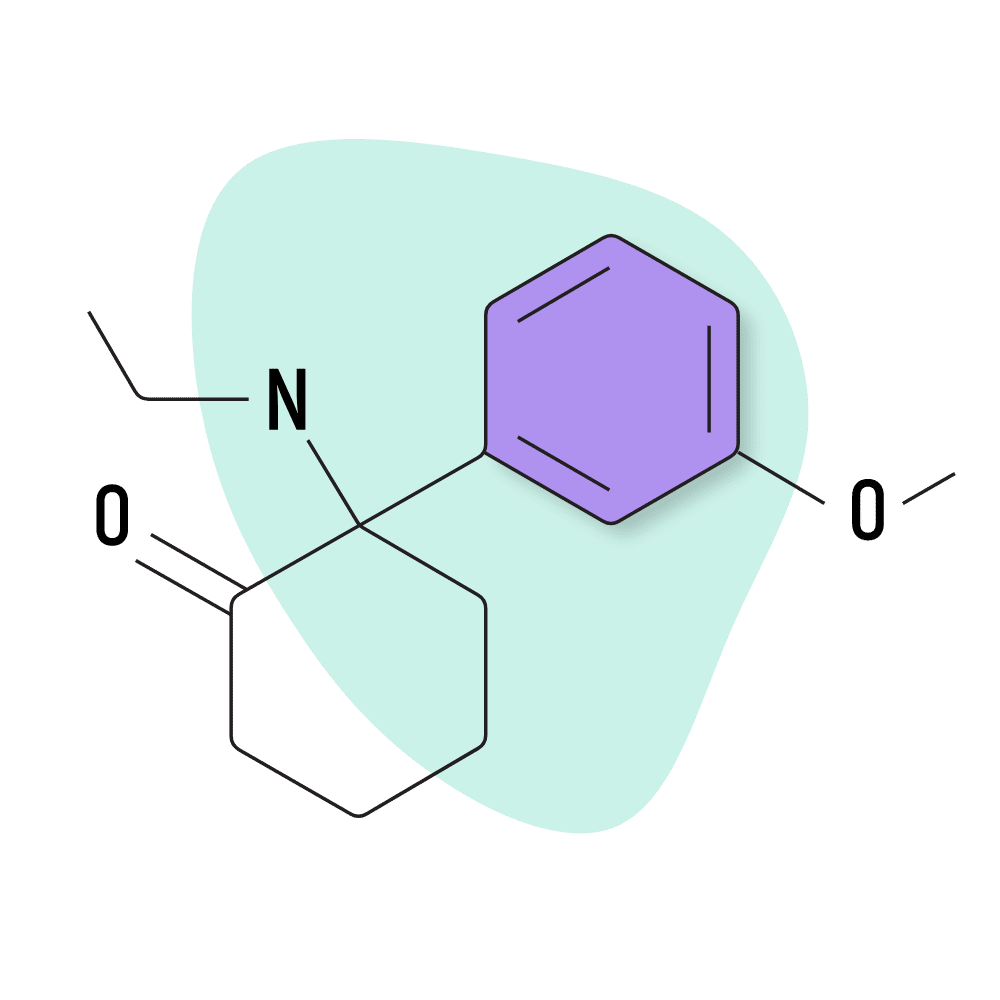

| Ketamine | Arylcyclohexylamine |

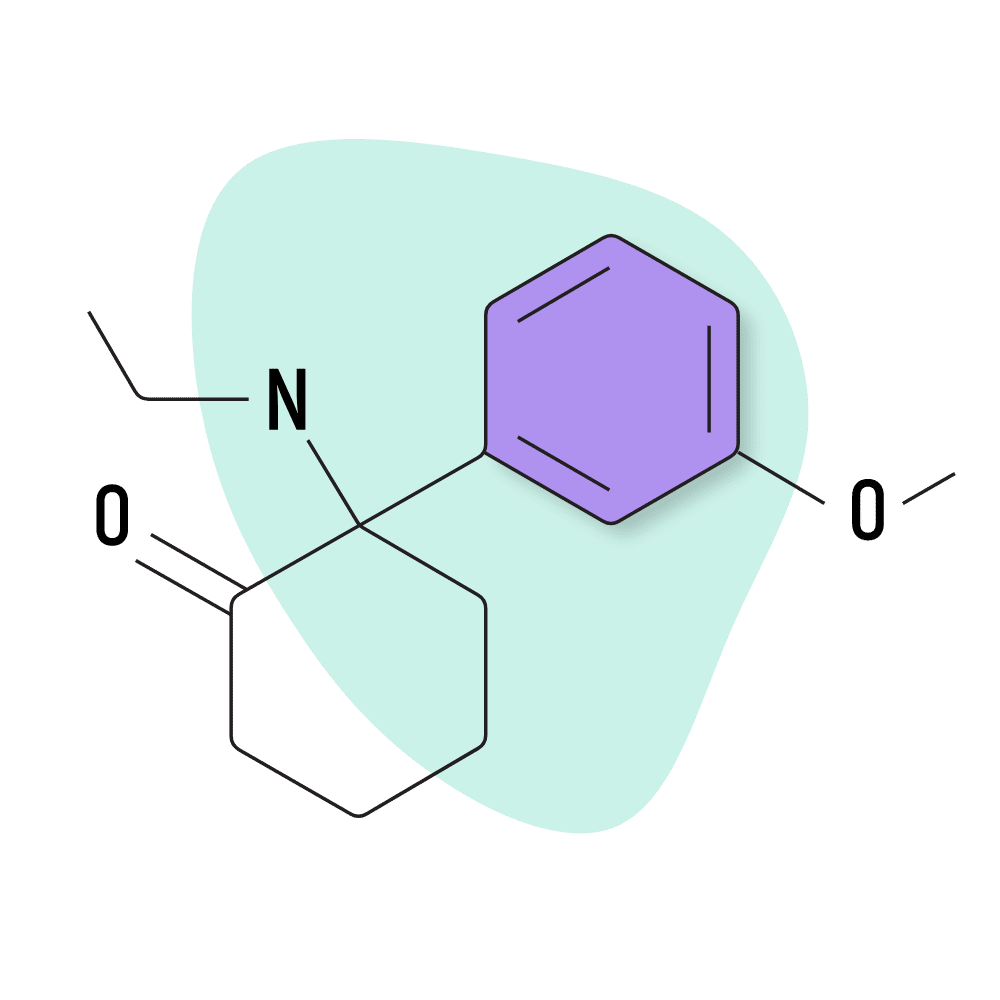

| Methoxetamine (MXE) | Arylcyclohexylamine |

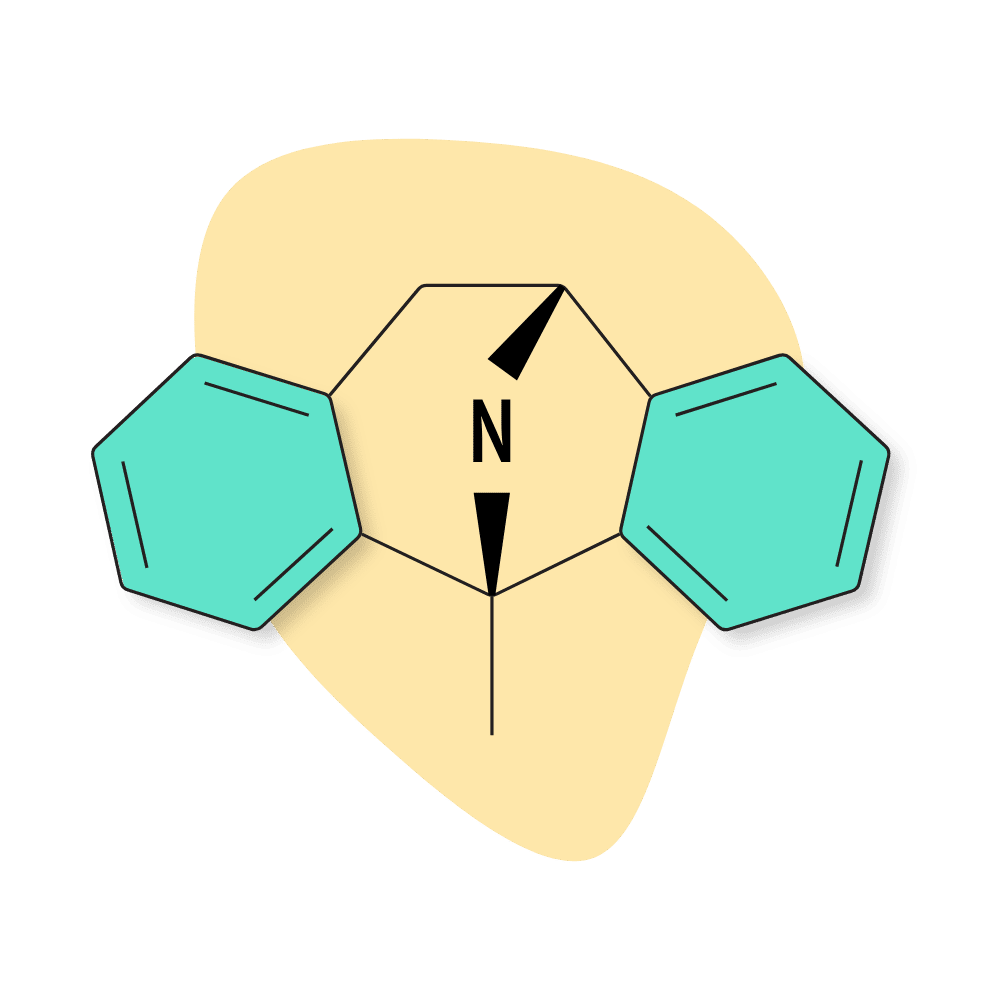

| MK-801 | Arylcyclohexylamine |

| Nitrous Oxide | Elemental |

| PCP | Arylcyclohexylamine |

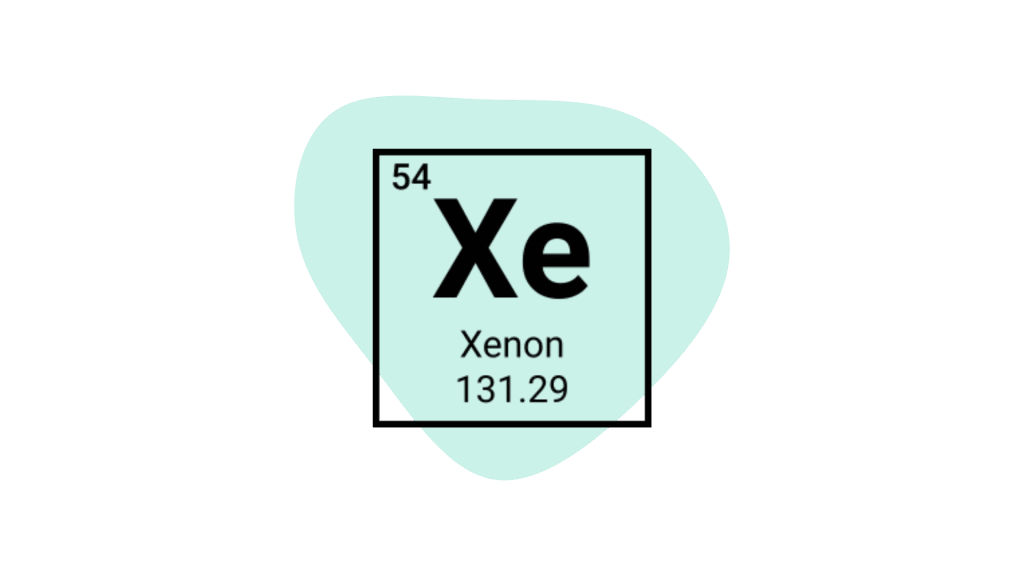

| Xenon | Elemental |

What is a Dissociative Drug?

Dissociative drugs (AKA ‘dissos’) are substances that decouple one’s first-person experience from reality. They dismantle the idea of “self” and alter one’s perception of reality.

Some dissociative reliably induce states that feel enlightening and enjoyable; others produce powerful hallucinogenic experiences that are almost always terrifying and traumatizing.

The effects of these substances vary by dose and substance — sometimes, users feel like they’re outside their body as a detached observer; other times, they’re injected into what feels like a separate reality entirely.

Dissociative drugs have conflicting effects — they’re stimulating and sedating, neuroprotective [6], and neurotoxic, and have addictive and anti-addictive [7] qualities. The effect comes down largely to which drug is being used, how often, and in what dose.

What Do Dissociative Drugs Feel Like?

The main feeling shared by all dissociatives is the detachment from the self or from the environment. This is the central component linking all dissociative substances together. The other effects depend on each individual substance.

Dissociative drugs tend to be very strong compared to other psychedelics. Their capacity to alter the perception of one’s physical reality is comparable to the potency of DMT or salvia.

Users often feel like they’ve teleported to another location or that the world around them has dissolved into nothingness.

Explaining the effects of deep dissociative states is no easy task. Language itself often proves insufficient for explaining these experiences.

Here are a few examples of people’s reports involving dissociative drug experiences:

- “It’s all close and far at the same time.”

- “My body died, but my mind had it’s own legs.”

- “I was caught in an endless time loop with my dad examining my fingerprints.”

- “I visited a place outside of time.”

People who use dissociatives will experience dream-like states of consciousness, including blurriness, difficulty making sense of events, confusion, detachment from emotion, and lapses in memory.

At the bottom of the dissociative state is a feeling of complete isolation and loneliness, but this state isn’t as uncomfortable as it sounds. Because of the lack of identity and absence of attachment, users feel as though they’re in a state of perfect zen.

Common experiences with dissociative drugs:

- Feeling like one is teleported to another location or dimension

- Loss of touch with the self & one’s identity

- Feeling like the limbs are being pulled & stretched

- Feeling like one is dissolving or exploding

- Observing oneself from outside the body

- Loss of touch with one’s emotional connection to objects, people, or locations

- Hallucinations of dark & malicious creatures or figures

- Paranoid or grandiose ideologies

- Tingling, numbing, or floating sensations throughout the body

- Loss of depth perception or flattening of the visual field

How Do Dissociative Drugs Work?

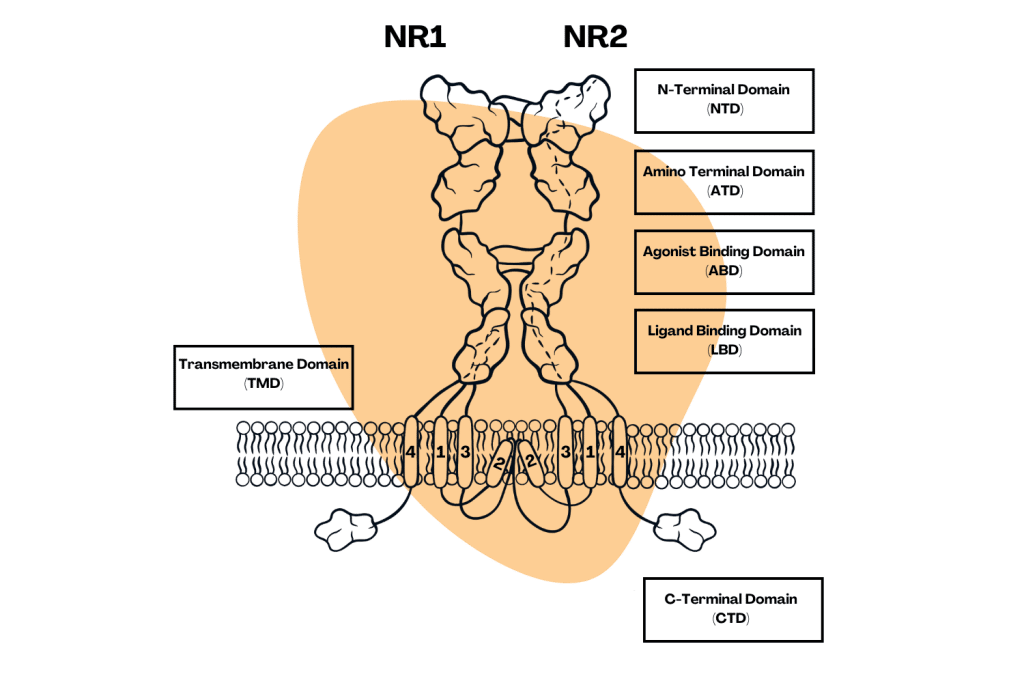

Most dissociatives produce the majority of their psychoactive effects by blocking the NMDA receptors. This is the primary mechanism of action for DXM, PCP, ketamine, nitrous oxide, MXE, xenon gas, and many others in this class.

Very high doses of classical psychedelics, including LSD, 2C-X compounds, DMT, and psilocybin, can also cause dissociation through the 5HT2A receptors — but this experience feels very different than dissociation caused by NMDA receptor antagonism.

What Are the NMDA Receptors?

NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors are one of three subtypes of glutamate receptors in the brain. The other two are the AMPA and kainate receptors.

NMDA receptors are found all over the brain but are most concentrated in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex [2]. Both of these brain regions are integral for processes involved with learning and memory. The cerebral cortex is involved with numerous other higher cognitive functions, such as consciousness, thought, emotion, reasoning, and language.

As such, blocking the NMDA receptors with dissociative drugs can influence all of these processes. They’re known to interrupt one’s capacity for learning, forming new memories, regulating emotions, processing language, and maintaining conscious thought [1].

High doses of an NMDA antagonist can cause the user to lose consciousness, which is what makes these drugs so useful for anesthesia.

What Are the Long-Term Effects of Dissociatives?

Most conventional dissociatives (ketamine, PCP, DXM, N2O) don’t leave lasting side effects after a single dose (when used responsibly).

Users often report feeling depressed or experiencing issues with memory and concentration immediately following use — but these effects usually disappear after a few days. This effect lasts the longest with PCP, MXE, and various analogs. N2O and xenon have the shortest duration residual effects of all.

Long-term consequences are more likely with habitual use of dissociative drugs.

The key to using dissociatives safely is to take them in moderation — there are no exceptions here.

Long-Term Mental Effects of Dissociatives

With repeated use, dissociative drugs have a tendency to gradually replace one’s inner thoughts and dialog with nonsense only they can understand.

People who use dissos on a consistent basis eventually find it more difficult to connect with others and may become more withdrawn from family, friends, and society.

Lasting depersonalization and derealization are also common. Users may start to feel like the people they interact with are all scripted or fake. There are a lot of reports of people believing they’re in a simulation or that some or all aspects of life are in some way falsified.

People using dissociatives long-term often experience problems with memory, concentration, emotional stability, energy levels, and sleep.

Each dissociative drug carries a different degree of risk.

High-risk substances like DXM, PCP, MXE, and MK-801 can start causing noticeable changes after just a few weeks.

Lower-risk dissociatives like ketamine, nitrous oxide, and xenon may take more time but will eventually produce similar side effects.

Long-Term Physical Effects of Dissociatives

Many dissociatives damage the kidney, liver, and bladder. Bladder disease is unusually common among habitual ketamine or PCP users (often referred to as “K-pains”). There are a few theories as to what causes this.

One study found that a metabolite from ketamine called norketamine had cytotoxic effects in the bladder, leading to fibrosis and chronic pain [5]. This effect has also been reported with other dissociatives in the arylcyclohexylamine family.

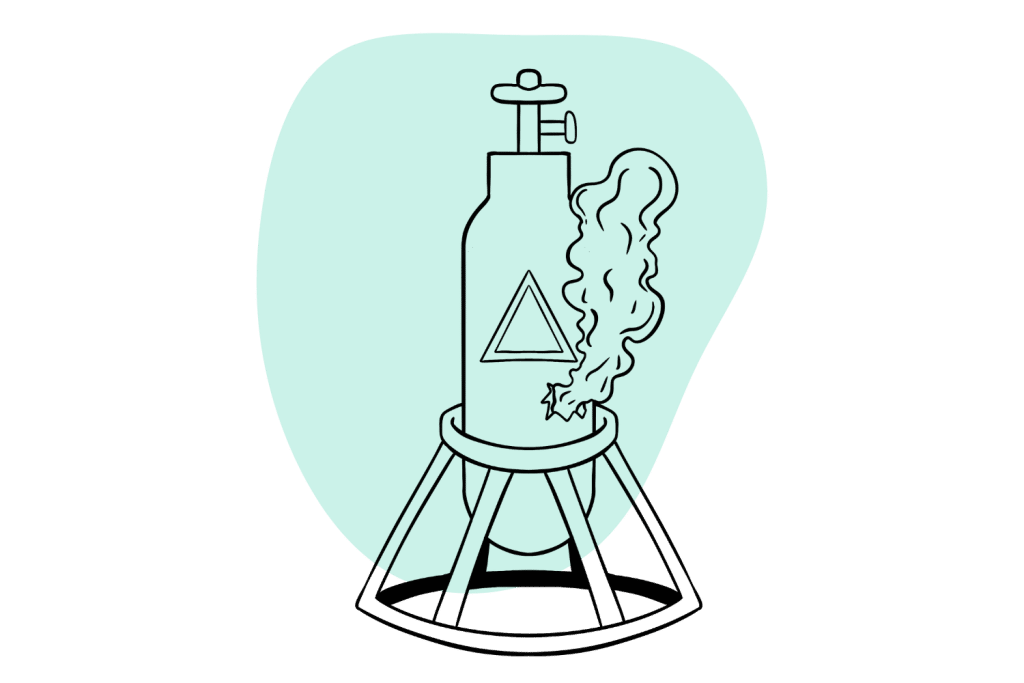

The inhalant group also carries some risk for long-term use. Inhaling low-quality or impure nitrous oxide or xenon gas can cause inflammation and damage to the lungs. Most of the N2O canisters on the market are not meant for inhalation and often contain manufacturing lubricants, solvents, or other toxic substances. Additionally, people using N2O without first allowing the gas to expand (such as by filling a balloon) can cause significant irreversible damage to the alveoli in the lungs.

Stimulating dissociatives, such as PCP, ketamine, DCK, O-PCE, and MXE, have all been linked with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke with long-term habitual use.

Why Do People Use Dissociative Drugs?

Dissociative drugs have a bad reputation. For example, PCP was a media sensation in the late 70s and 80s where it was portrayed as an evil drug that turns normal citizens into face-eating monsters.

While there are certainly horrors to PCP and other dissociative drugs (especially in high doses or long-term use) — many of these reports have been grossly overexaggerated.

Most dissociatives, when used at the right dose and in moderation, aren’t going to result in significant side effects or turn people into blood-thirsty monsters.

In fact, there are some legitimate uses for dissociative drugs — both official and unofficial. Likewise, some motivations for using these drugs cause more harm than good.

1. Anesthesia

Dissociated states are useful as anesthesia in medical settings. PCP was the first chemical anesthetic ever used but was replaced a few years later by ketamine. Nitrous oxide is also commonly used for anesthesia. Xenon gas is considered the “perfect anesthetic” because it’s non-toxic, fast-acting, and provides thorough anesthesia. The only downside is it’s extremely expensive.

2. Mental Health, Shadow Work, & Ego-Death

Some dissociatives, such as ketamine, show promise as a treatment for depression and PTSD.

In a state of complete dissociation, users temporarily attain a zen-like state of consciousness. This experience is similar to ego-death, but the detachment effect removes uncomfortable feelings of fear and grief that come along with it. All the shame, worry, anger, and discontent someone may feel in waking consciousness are gone. They enter a purely meditative, nearly thoughtless state of being.

Within this state of consciousness, one can identify their undesirable traits and feel their insignificance in the universe. Normally, this type of realization results in an overwhelming sense of fear, panic, and sadness — but with dissociates, users could care less.

Complete dissociation is a lonely place to be, but more often than not, users feel blissful and whole rather than scared and alone.

Ketamine allows a person to take an unbiased look at the self and identify suppressed unconscious behavior (Carl Jung refers to this process as shadow work), but without experiencing the pain and discomfort that accompany these realizations — this is one of the core ways ketamine is so helpful for depression and PTSD.

Unfortunately, this dissociative effect is limited. This first experience is usually productive, but subsequent use will never quite bring them to this dissociative zen state again.

Over time, these drugs just start degrading the mind and cause the user to become more disconnected, more isolated, more depressed, and less aware of their unconscious patterns than ever before.

3. An Escape From Reality

Many people use drug-induced escapism as a coping mechanism, as a way to deal with feelings of hopelessness, grief, or other negative emotions. Dissociatives and strong analgesics are often the drugs of choice for this effect because of their capacity to temporarily induce a state of bliss and mute one’s inner dialog.

Others use dissociative drugs for experimental escapism. K-hole or breakthrough-level experiences are not hard to achieve with dissociatives and are some of the trippiest experiences one can achieve — to the point where language is insufficient in explaining the experience to others.

Most people aren’t in for this level of experience, which can also occur at high doses of magic mushrooms, LSD, and DMT — but some people thoroughly enjoy these deep, often confrontational experiences.

In either case, escapism is not a healthy reason for using any substance — especially dissociatives. These drugs have a glow at first, but their positive effects can take a quick turn in the opposite direction. The road leads to depression, delusional thought patterns, memory loss, and further disconnection from the self.

Dissociative drugs “feel” enlightening at first (and perhaps they are to some degree), but long-term or repetitive use is antithetical to the process of self-improvement.

4. Drugs of Deception

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, authorities first started reporting an influx of cases of bunk LSD, mescaline, cocaine, psilocybin, MDMA, and marijuana being laced with or replaced with PCP.

While much of this is overexaggerated, PCP and its various analogs are cheap to make and produce powerful effects even in very small doses — so it’s a common adulterant of choice for clandestine drug manufacturers.

The existence of safe testing sites at festivals and raves and at-home reagent drug testing kits have done a lot to combat this issue, but it still remains a problem.

TL;DR: Buy a drug test kit and keep it in your freezer until you need it.

What Are the Most Common Dissociative Drugs?

A lot of drugs have dissociative effects — but seven have achieved widespread popularity.

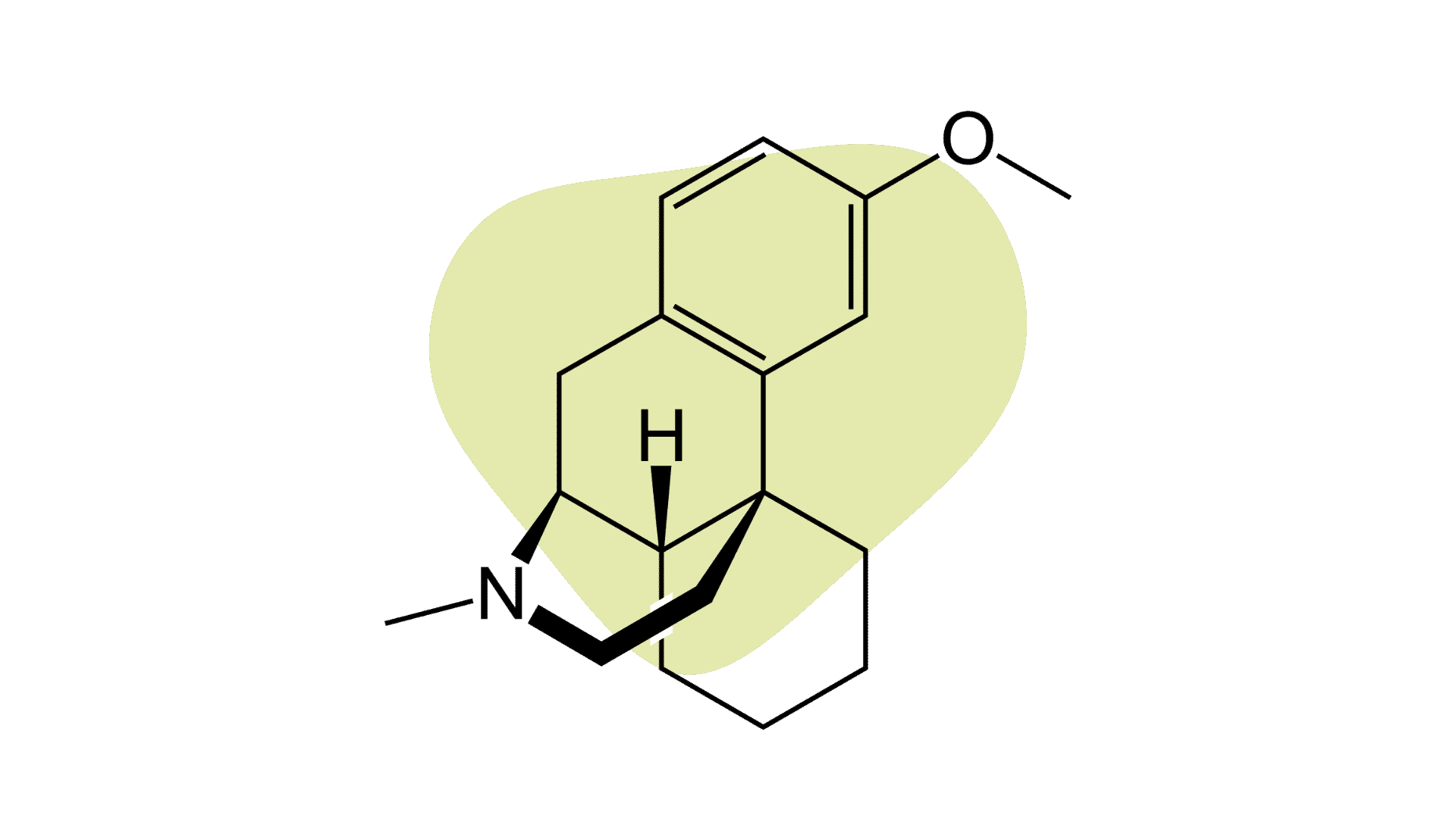

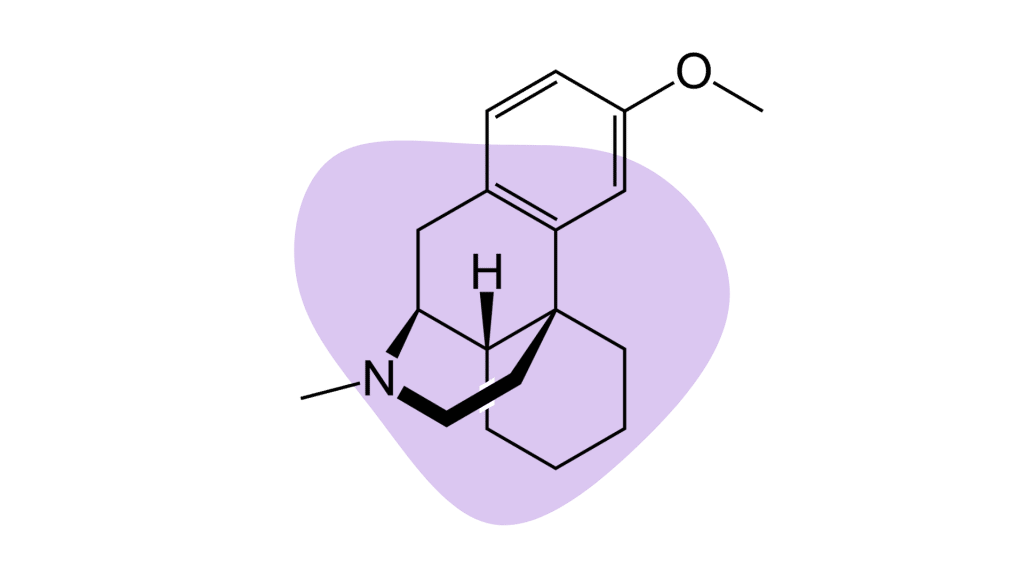

1. DXM (Dextromethorphan)

DXM (dextromethorphan) is the active ingredient in many over-the-counter cough medicines. In low doses, it’s a safe and effective antitussive agent (a substance that prevents coughing), but it’s a potent dissociative psychedelic in higher doses.

There are four distinct plateaus for DXM depending on the dose:

- The first plateau is associated with feelings of euphoria and mild-moderate tipsiness.

- The second plateau has a much more drunk feeling while maintaining euphoria and some mild dissociation.

- The third plateau is highly dissociative, often causing users to lose consciousness periodically and stumble around like a robot.

- The fourth plateau feels a lot more like PCP or ketamine, with deliriant effects and substantial dissociated hallucinations.

DXM can become addictive over time and is associated with all the problems inherent to dissociative drug use. Frequent users experience problems with memory, concentration, and imagination.

Overdoses are also possible, which can lead to hospitalization and death.

The most significant issue is the presence of acetaminophen or other medications in over-the-counter cough medicine. These medications can cause irreversible liver or kidney damage if used in the dosages required for the psychoactive effects of DXM.

2. Ketamine

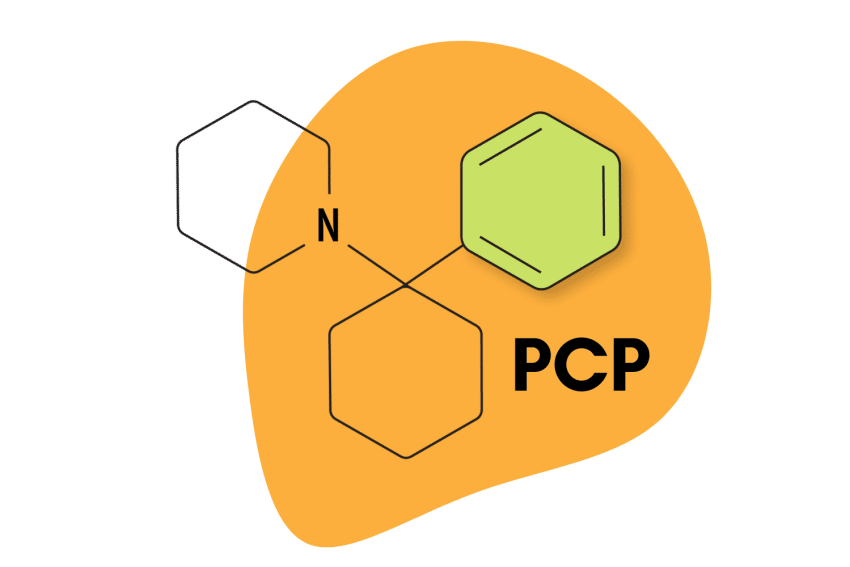

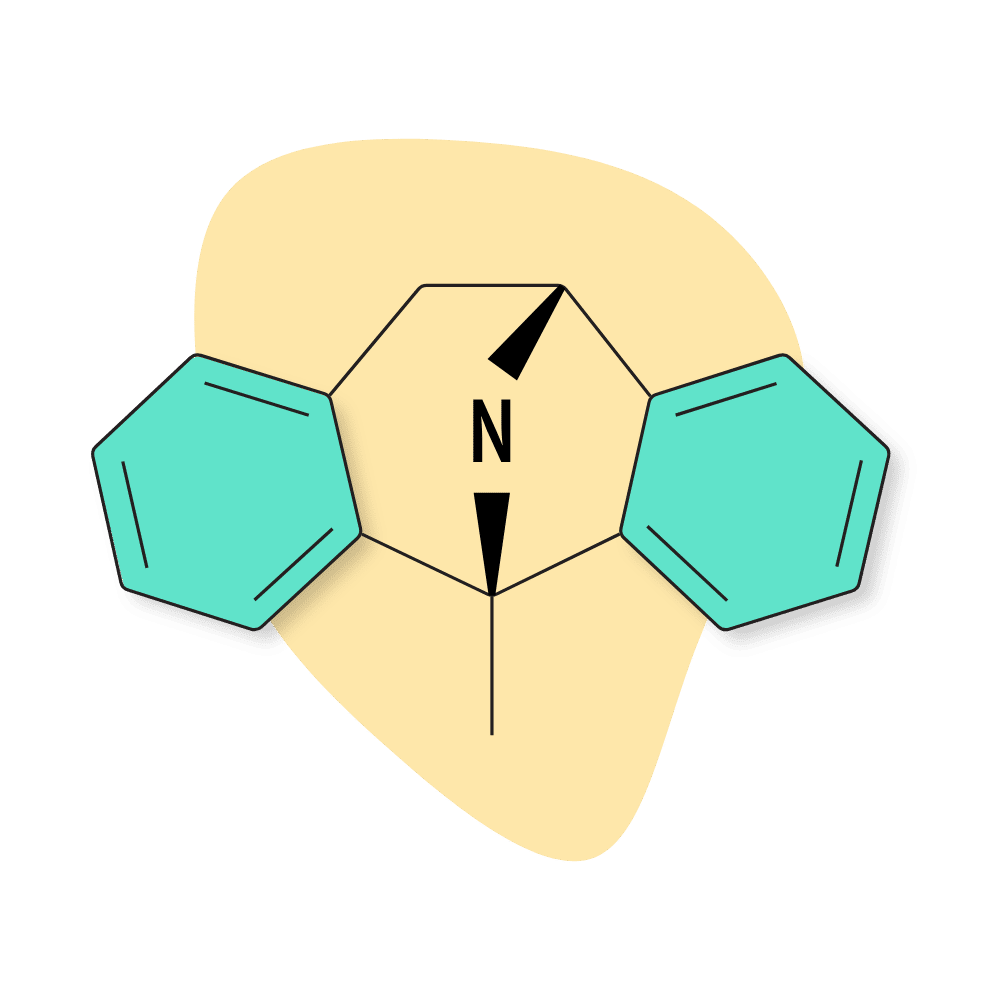

Ketamine was invented to replace PCP as an anesthetic agent during surgeries. Chemically, ketamine is a member of the arylcyclohexylamine family, many of which are both dissociative and hallucinogenic.

The effects of ketamine are highly dose-dependent. People who take lower doses feel effects similar to being drunk and a little bit high from MDMA or other stimulants. Users feel as though they’re floating or that their body is on autopilot.

In moderate doses, ketamine’s effects are more dissociative and psychedelic. The “autopilot” effects become more pronounced, vision becomes dark and hazy, and users become withdrawn and introspective. Out-of-body experiences are possible with moderate doses and tend to come and go over the course of the experience.

In high doses, ketamine is anesthetic and can cause users to lose consciousness for a few minutes as they fall into what’s referred to as a K-hole. During this experience, boundaries of the ego are broken, and the user feels as though they’re falling endlessly into darkness. The very fabric of time and existence is challenged, but the suppression of emotions and connection with the body prevent this experience from being scary or uncomfortable.

3. Methoxetamine (MXE)

MXE is a research chemical and member of the arylcyclohexylamine chemical family. It’s closely related to ketamine and PCP and is often sold as a “legal alternative” to these well-known psychedelics.

Methoxetamine first appeared on the market around 2010, but little is known about its long-term impact on the body. There are no human studies on this compound and only a handful of animal studies compare safety and dosage.

MXE is compatible in potency to ketamine and much weaker than PCP. Its effects are described as euphoric, stimulating (higher doses), and relaxing (lower doses). The dissociative effects make users feel calm and relaxed. Users experience a separation from emotions and feel like they have nothing to worry about — a key element of the dissociative effect that’s shared by both ketamine and PCP.

In higher doses, the dissociative effects become much more hallucinogenic and can lead to K-hole states. However, unlike other MXE doesn’t do as good of a job at removing feelings of fear or grief — so it’s much more likely to experience a bad trip on this drug after taking too much.

Unfortunately, taking too much MXE is relatively easy because of how long it takes to kick in. Even people who snort the drug often report waiting 30–60 minutes before they feel the effects. Impatient users may take a second dose before the first one has time to kick in, leading to an overdose.

Overdosing on MXE can be fatal. People who recover often require several days of hospital care, and some exhibit long-lasting mental and physical side effects. There are plenty of horrible trip reports associated with MXE.

4. Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous oxide has been used for anesthesia and recreational use for hundreds of years. Upper-class “laughing gas” parties were reported in Great Britain as early as 1799.

The experience is similar to other dissociatives — only sped up. It kicks in quickly but fades out again just as fast.

The gas is administered via inhalation. Within a few seconds, the user starts to experience dizziness and may hear whooshing sounds as vision becomes faded and hazy.

This substance is called laughing gas because users have a tendency to burst out in hysterical laughter. This emerges spontaneously as a result of the intense confusion and euphoria. People lose touch with who they are and where they are — but don’t care because of how dissociated from the self they’ve become.

After exhaling, the effects remain for a few seconds (20–45) before fading out just as quickly as they appeared.

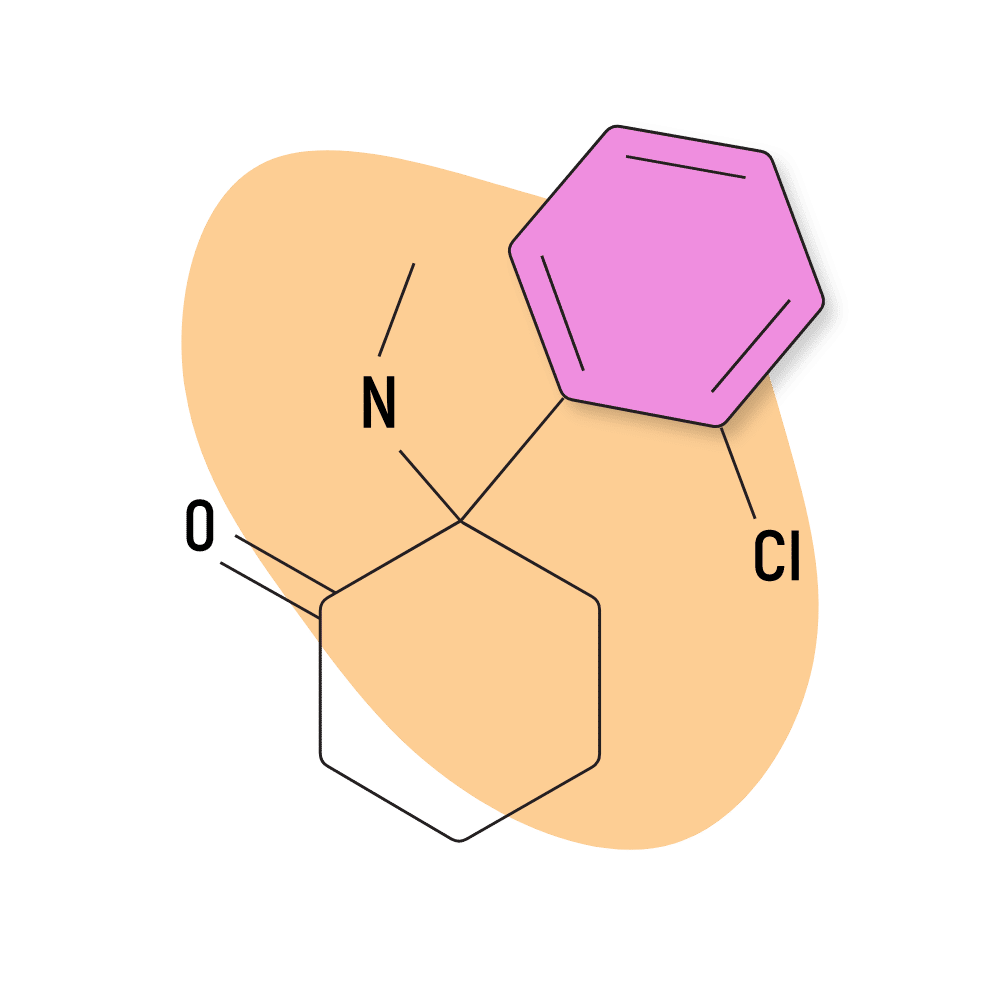

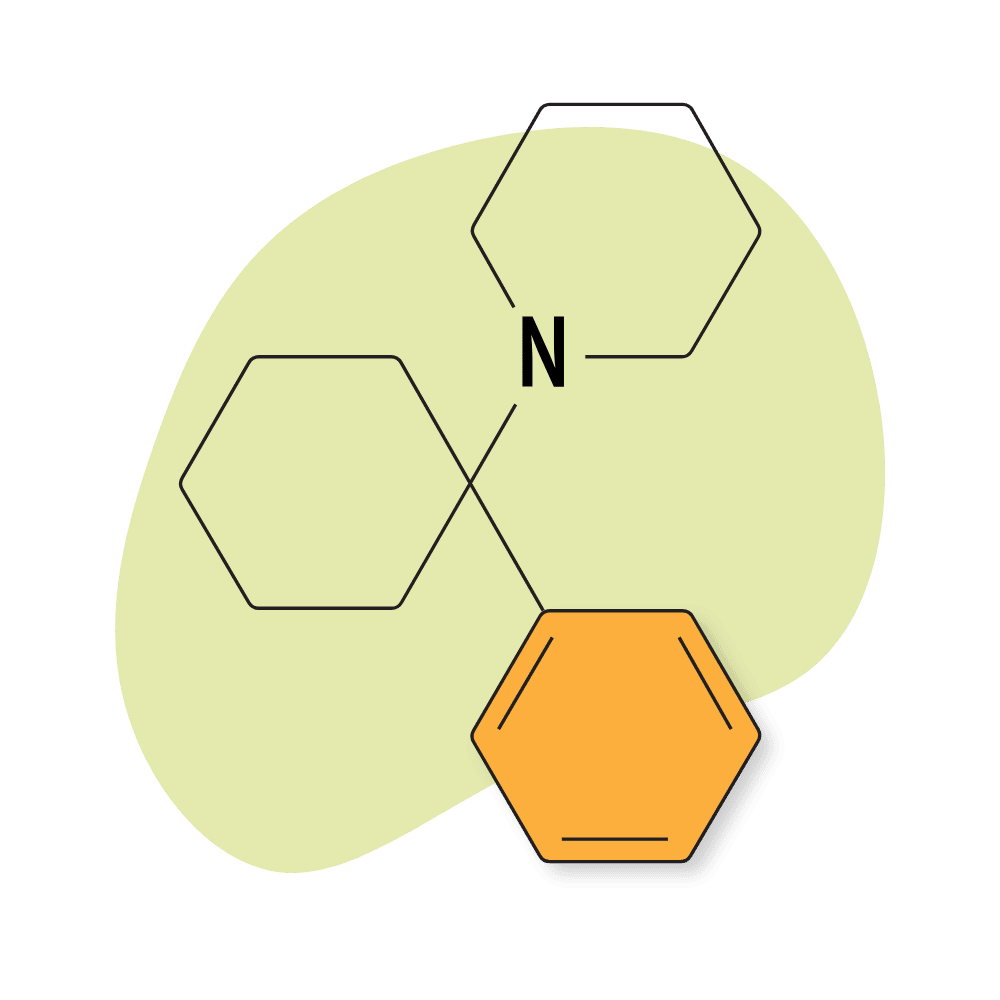

5. PCP (Phencyclidine)

PCP (phencyclidine) has been around for a long time. It was invented in 1926, but wasn’t patented until the 1950s. It was used for a few years as an anesthetic agent in the 60s. However, it was quickly replaced with ketamine because roughly one in five patients would exhibit severe responses to the drug — often lasting 12 hours or more.

Most people who use PCP smoke it by either spraying it over leaf material (usually tobacco, marijuana, or oregano) or dipping a cigarette in a solution of liquid PCP.

The effects of PCP are undeniably dissociative but with more stimulating effects than other members of this class. PCP is considered a “dirty drug” because it interacts with numerous separate receptors in the brain. The primary effect comes from its ability to block the NMDA receptors, but it also interferes with serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine — resulting in an experience distinct from most other dissociative compounds.

Lower doses of PCP have a speedy feel. Users feel confident and energized — like they could do anything. It’s hallucinogenic, but this effect is mild in lower doses. Most people report feeling as if they’re on autopilot or are watching themselves from somewhere else — but remain largely in control of their actions.

High doses of PCP are very different. The hallucinogenic effects become much more pronounced, and the dissociation becomes severe. Many people experience lapses in memory and feel as though some of their voluntary control is lost.

6. Xenon

Xenon gas is a pure element listed on the periodic table (atomic number 54). It’s one of seven noble gases, which are characterized by their lack of reactivity with other elements.

This element is found in very low concentrations in the atmosphere but can be extracted through fractional distillation of liquid air.

Because of the low reactivity of this element, there aren’t many uses for xenon. However, it does have powerful dissociative and euphoric effects in humans. Inhalingxenon feels similar to nitrous oxide but much stronger and more euphoric. The effects are described as “flipping a switch for euphoria” in the brain.

Because of the strong dissociative effects, xenon is used for anesthesia in hospitals and is considered by many to be an idyllic anesthetic agent.

Xenon gas is often referred to as the “perfect anesthetic” for four main reasons:

- It’s fast-acting — xenon kicks in within a few seconds.

- It’s potent — xenon is capable of complete anesthesia without the help of other anesthetic substances.

- It wears off quickly — once the surgery is over, xenon is shut off, and the user regains complete consciousness within 15 minutes.

- It boasts an impressive safety profile — xenon is (mostly) inert and will not interact with other medications or lead to harmful metabolites.

While no long-term side effects have been noted, this is more likely due to the absence of habitual users than from a total lack of negative side effects. A single dose of xenon can range anywhere from $40–$100 and only provides enough gas for about 3 minutes of experience.

Most people simply can’t afford to abuse xenon.

7. MK-801

MK-801 (AKA Dizocilpine) was first discovered by Merck in 1982. It was first developed as a new anesthetic and anticonvulsant agent but was never adopted into clinical use after researchers discovered the drug had an affinity for causing Olney’s lesions in rats.

Olney’s lesions are known to occur with high dose or long-term use of NMDA antagonists, including ketamine and PCP. These lesions are characterized by a reduction in white matter in the brain — leading to cognitive deficits and memory loss. Today, MK-801 is used for inducing psychosis in animal models for research purposes.

Despite the downsides, MK-801 remains relatively popular as a recreational drug. People like it because it’s substantially stronger than ketamine and PCP and much longer-lasting. MK-801 trip reports often describe horrible experiences lasting several days — and many exhibit long-term dissociation and apathy.

Other Dissociative Research Chemicals

There are a lot of newer dissociative drugs that have hit the market since the early 2000s [3]. The vast majority of these research chemicals have not had their safety profiles officially studied.

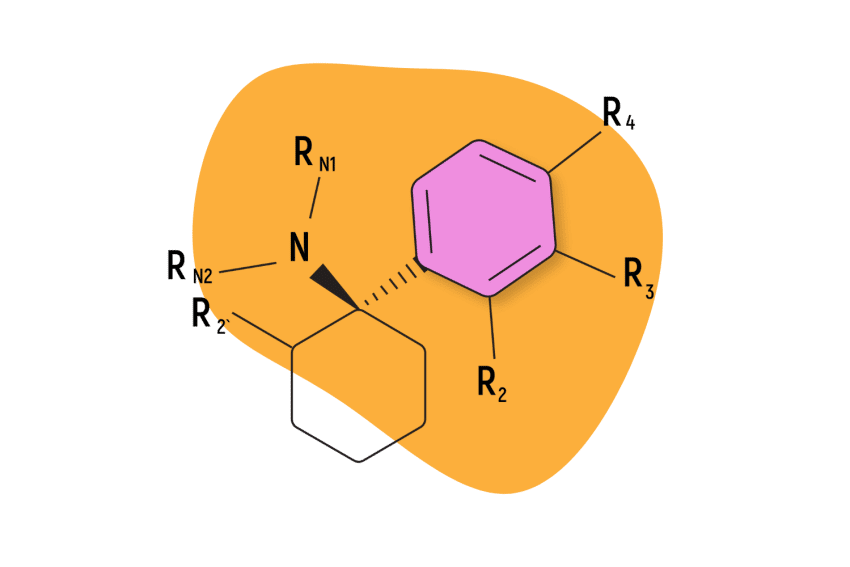

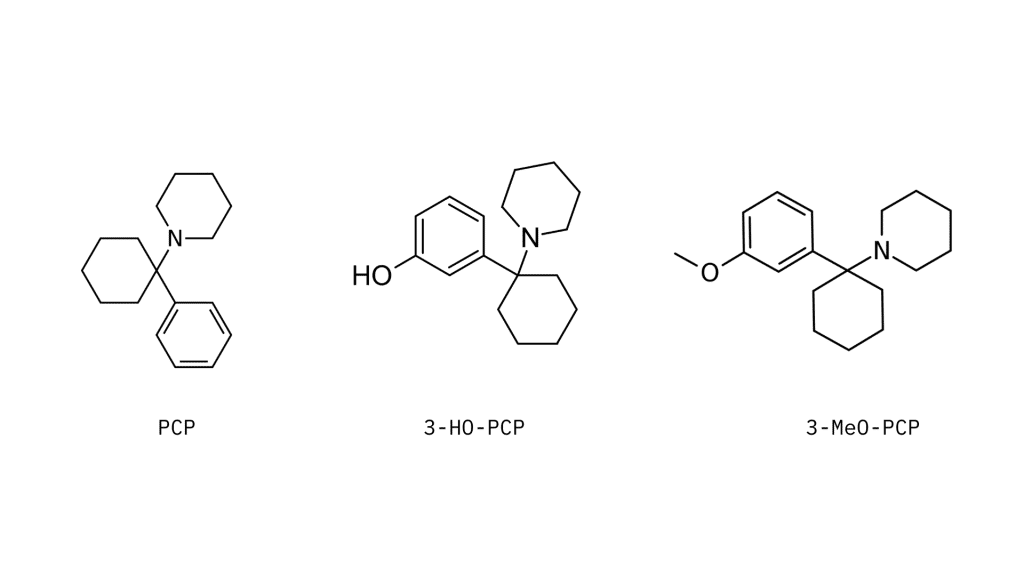

PCP Analogs

PCP analogs include 4-MeO-PCP, 3-HO-PCP, 3-MeO-PCP, 3-CL-PCP, and 3-FL-PCP.

Some of these analogs, namely 3-HO-PCP and 3-MeO-PCP, are considered milder than conventional PCP and less likely to make users feel delusional or unable to interact effectively with the world around them.

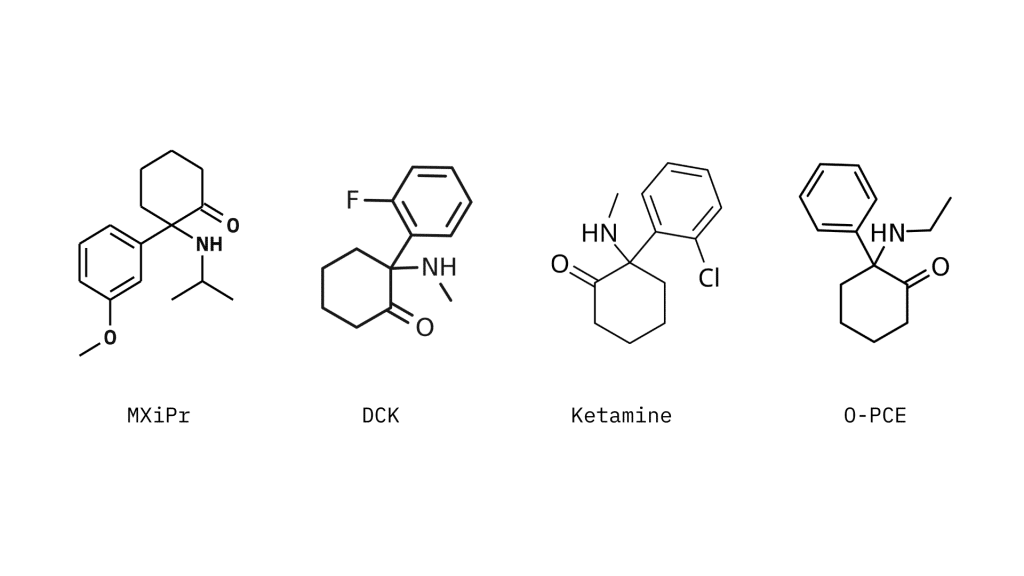

Ketamine Analogs

Ketamine analogs include deschloroketamine (DCK), tiletamine, methoxisopropamine (MXiPr), and O-PCE.

The effects of these compounds vary substantially — some stronger, some weaker. None of them have been proven safe for human consumption.

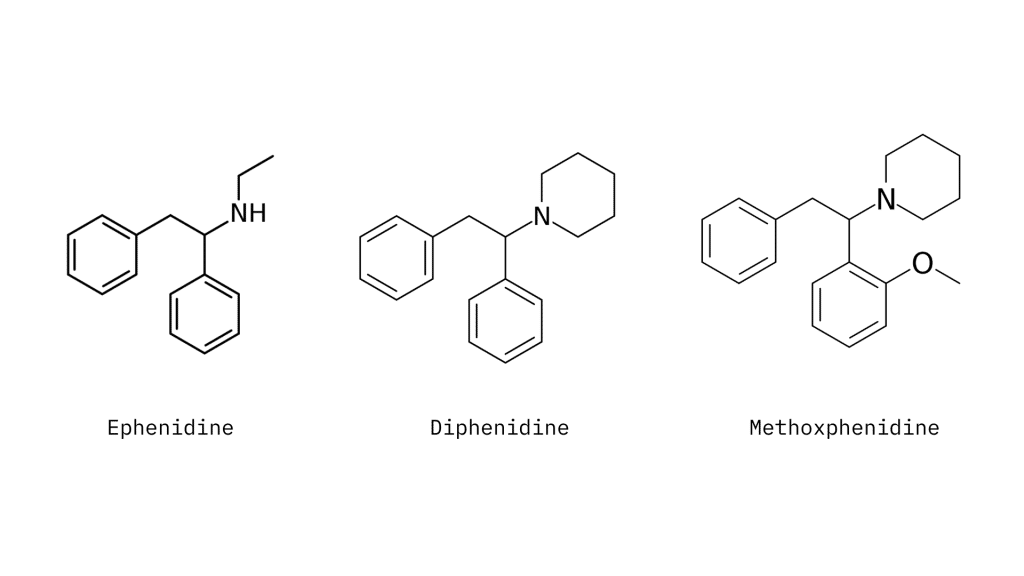

Diarylethylamine Drugs

Diarylethylamines are a newer class of drugs designed specifically for recreational use. They were invented as a way to side-step laws banning conventional dissociatives like ketamine and PCP. None of the drugs in this class have been proven safe, and several have been found to carry a far greater risk to mental and physical health than the drugs they were meant to replace.

Compounds in the diarylethylamine drug class include ephenidine, diphenidine, and methoxphenidine.

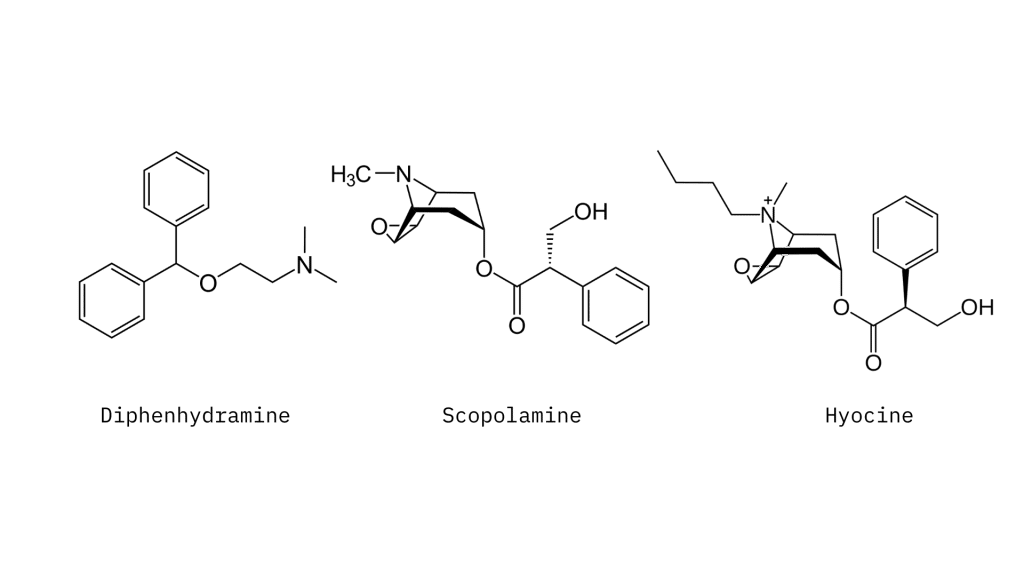

Deliriant Dissociatives

Drugs like orphenadrine, diphenhydramine (DPH), and dimenhydrinate that are primarily classified as deliriants (drugs that induce a state of delirium), may also possess dissociative qualities.

Some natural deliriants like Amanita muscaria, datura, nutmeg, Brugmansia, and mandrake root can produce feelings of dissociation in lower doses or as the effects start to kick in.

Sometimes the dissociated feeling goes away as the deliriant effect starts to kick, as is the case with datura.

In other cases, users remain in a dissociated delirium throughout the experience, as with DPH and dramamine.

Dissociative Terms & Definitions

- Amnesia — a loss of memories, including facts, experiences, or other information.

- Anesthesia — a controlled, temporary loss of awareness and sensation used for surgery or emergency medicine.

- Catalepsy — a neurological condition involving rigid or fixed posture.

- Delirium — an inability to think clearly or differentiate real experiences from imagined ones.

- Depersonalization — a sense of detachment within the self. Subjects feel as though they’re observing themselves from outside the body or remain in the body but detached from all elements of self, including personal connections, emotions, or relationships.

- Derealization — feelings that the external world is fake or unreal. Mild experiences involve a lack of depth or emotional coloring; strong experiences involve a sense that the world and one’s own identity are fake or falsified.

- Dissociation — a sense of separation from the self and/or the environment.

- Ego-Death — a temporary loss of ego caused by psychedelic drugs, near-death experiences, deep meditation, or childbirth.

- Glutamate — the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain.

- NMDA Receptors — N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors are one of three glutamate receptors present on the surface of neurons. The other two are kainate and AMPA receptors.

References

- Newcomer, J. W., Farber, N. B., & Olney, J. W. (2000). NMDA receptor function, memory, and brain aging. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 2(3), 219.

- Kumar, A. (2015). NMDA receptor function during senescence: implication on cognitive performance. Frontiers in neuroscience, 9, 473.

- Morris, H., & Wallach, J. (2014). From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs. Drug testing and analysis, 6(7-8), 614-632.

- Zhou, Y., & Danbolt, N. C. (2014). Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. Journal of neural transmission, 121(8), 799-817.

- Chu, P. S., Kwok, S. C., Lam, K. M., Chu, T. Y., Chan, S. W., Man, C. W., … & Lau, F. L. (2007). Street ketamine’-associated bladder dysfunction: a report of ten cases. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 13(4), 311.

- Clifford, D. B., Olney, J. W., Benz, A. M., Fuller, T. A., & Zorumski, C. F. (1990). Ketamine, phencyclidine, and MK-801 protect against kainic acid‐induced seizure‐related brain damage. Epilepsia, 31(4), 382-390.

- Ezquerra-Romano, I. I., Lawn, W., Krupitsky, E., & Morgan, C. J. A. (2018). Ketamine for the treatment of addiction: Evidence and potential mechanisms. Neuropharmacology, 142, 72-82.