A Refresher on How Drug Scheduling Works in the United States

The process of scheduling drugs is complex, involving contributions by the DEA, FDA, and HHS — all of our favorite organizations 😒

The United States federal government controls drugs through the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which was first established during the Nixon administration in 1970.

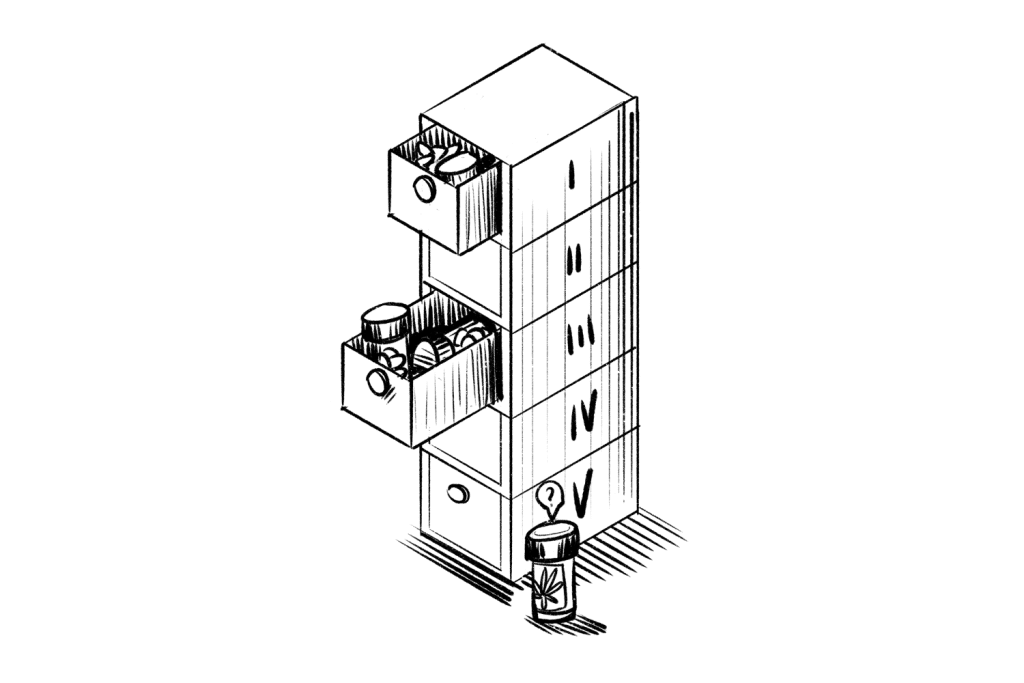

This Act categorizes drugs into five separate schedules — each involving various levels of severity for those caught possessing substances within that category.

Schedules are differentiated based on criteria such as medical value and their potential for causing dependency and the risk of overdose.

An alphabetical list of all controlled substances can be found on the DEA website.

Here’s how drug scheduling currently works in The United States of America (USA).

Overview of the DEA’s Drug Scheduling System

The DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) creates and regulates drug schedules, but other agencies are involved as well — such as the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

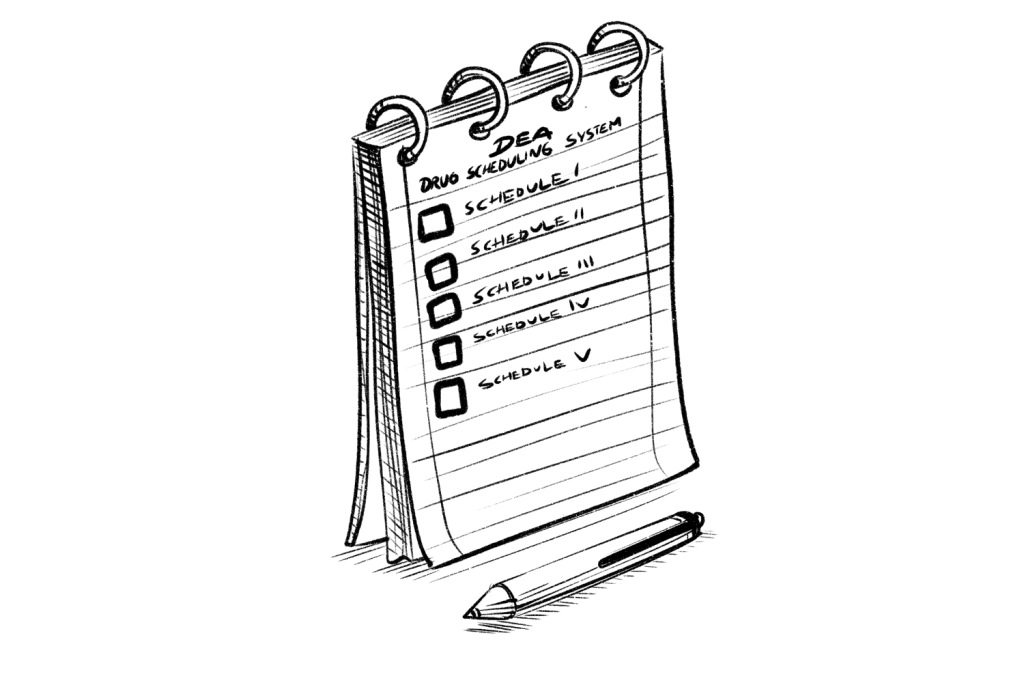

Below is a broad overview of the five schedules and a list of some of the best-known drugs and substances found in them.

Schedule I drugs are considered to have the highest potential for dependency and abuse, and Schedule V has the lowest.

Substances in Schedule I are not accepted for medical use, unlike those in Schedules II-V. Drugs and substances in Schedules II-V are subject to varying levels of control but, unlike substances on Schedule I may be given to patients with a prescription.

Schedule I drugs may never be legally manufactured, possessed, or distributed. Pharmaceutical companies, distributors, and pharmacies may manufacture and distribute drugs on Schedules II-V as long as they observe applicable laws.

Drug Schedule Chart

| Drug Schedule | Definition | Examples |

| Schedule I | Schedule I drugs are not accepted for medical use and are considered to have a high potential for abuse. | Heroin LSD Magic Mushrooms Marijuana Ecstasy |

| Schedule II | Schedule II contains drugs with known medical value but carry a high risk of abuse. | Cocaine Methadone Oxycodone Fentanyl Adderall Ritalin |

| Schedule III | Schedule III substances have a lower potential for abuse than those in the previous two schedules. Abuse also leads to lower physical dependence than drugs found on Schedule I and II. | Ketamine Testosterone Anabolic Steroids |

| Schedule IV | Drugs in Schedule IV have a lower potential for abuse and dependence than Schedule III drugs. | Xanax Valium Tramadol Ativan Darvon |

| Schedule V | Drugs and substances on Schedule V have an even lower risk for dependence and dependency than Schedule IV drugs and are generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. | Parepectolin Motofen Lyrica Codeine |

Drug Scheduling Procedure in the USA

The CSA regulates the procedure of adding, removing, and transferring substances between the different schedules. The decision-making agencies for these matters are the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), with help from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

As we will elaborate on below, drugs can be rescheduled. The DEA and FDA can initiate these changes, but Congress and citizen or sponsor petitions can as well.

The procedure for scheduling drugs and substances is laid out in Section 201 of the CSA.

1. FDA Assessment

Initially, the DEA sends the request to HHS. This task is then delegated to the FDA, which conducts an investigation and collects relevant scientific and medical data to consider whether a drug can be abused. The FDA also receives evaluations and input from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

If the FDA determines that there is potential for abuse, based on its scientific assessment, it makes a recommendation to the DEA, regardless of how low the potential may be.

When determining whether or not to schedule a drug or substance, the relevant agencies mentioned above look at a total of eight different questions set out in 21 USC 811:

The following questions are used when assessing a substance’s potential for abuse:

- Its actual or relative potential for abuse.

- Scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, if known.

- The state of current scientific knowledge regarding the drug or other substance.

- Its history and current pattern of abuse.

- The scope, duration, and significance of abuse.

- What, if any, risk there is to public health.

- Its physical or physiological dependence liability.

- Whether the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already controlled under this subchapter.

As stated before, if there is enough potential for the drug to be useful for medical purposes, it should not be put on the most restrictive schedule — however, we know this isn’t always the case.

A drug needs to be extensively tested in clinical trials, and its results are then analyzed

to determine its medical value.

Its abuse potential is also analyzed to see if recreational use can result in personal health problems or pose risks to society as a whole.

However, the exact criteria and terms (such as “abuse”) are not clearly defined in the CSA, leaving a lot of room for interpretation by decision-makers. This has led to controversies — marijuana and psychedelics, for example (as you’ll see below).

2. DEA Assessment

After receiving a recommendation from the HHS (based on recommendations from the FDA), the DEA reviews the collected materials and places a drug or substance on a schedule.

If the HHS recommends that a drug does not need to be controlled, the DEA may agree. However, the DEA administrator makes the final decision.

The DEA has 90 days to place a drug on a schedule from the time it receives the HHS recommendation.

The DEA’s final decision is subject to judicial review, but this is more of a formal requirement, as federal courts tend to agree.

3. Temporary Scheduling of Substances by the Attorney General

The CSA also gives authority to the attorney general to temporarily place unscheduled substances in Schedule I if he or she finds it necessary to do so in order to avoid an imminent hazard to public safety.

The attorney general delegates this authority to the administrator of the DEA. Such temporary scheduling can be done for up to two years and extended for one additional year. The DEA then needs to determine whether the substance in question is to be permanently scheduled or whether it does not need to be scheduled after all.

The Federal Analogue Act

One noteworthy section of the CSA is the Federal Analogue Act, passed in 1986.

The Federal Analogue Act states that chemicals that are “substantially similar” to drugs or substances in Schedule I or Schedule II of the CSA and “intended for human consumption” are to be treated as if they were scheduled.

This section of the Act intends to address the issue of the so-called “designer” or synthetic drugs developed to imitate banned drugs by using similar chemicals that result in similar pharmacological effects as those of the controlled substances.

The Federal Analogue Act is considered controversial by many. For instance, the Act does not define what “substantially similar” means.

This leads to issues when legal professionals have to consider whether a designer drug’s chemical composition and effects are “substantially similar” to the substances it tries to replicate. This matter leaves a lot of room for interpretation.

Previous cases have shown that prosecution under the Federal Analogue Act is tricky, and it’s argued that the wording of the Act is “unconstitutionally vague,” as in the case of McFadden v. United States.

Related: What Is the Federal Analogue Act?

Can Drugs Be Rescheduled?

From time to time, drugs are reclassified, although this is rare.

An example of such a process was rescheduling hydrocodone combination products from Schedule III to Schedule II in 2014.

Michele Leonhart from the DEA indicated that this change was needed due to the dangerous potential of medications containing hydrocodone. She stated that “Today’s action recognizes that these products are some of the most addictive and potentially dangerous prescription medications available.”

Hydrocodone combination products were reclassified after a doctor initiated it through a petition in 1999. The DEA requested the United States Department of Health and Human Services evaluate such substances and recommend their categorization. In 2013, the FDA held an advisory committee meeting where a majority vote decided to move hydrocodone-containing products to Schedule II.

Marijuana is often subject to discussion due to its placement on Schedule I.

Many experts agree that it only has a moderate risk of addiction and offers great potential for medical use, for instance, for cancer patients. Despite a large movement requesting the rescheduling of marijuana, the DEA decided in 2016 that it would remain in Schedule I.

However, in October 2022, President Biden requested the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services to “initiate the administrative process to review expeditiously how marijuana is scheduled under federal law.”

Time will tell whether there will be a change to the scheduling of marijuana. It certainly looks more hopeful now than it did in the past.

Some psychedelics show so much promise for treating mental health conditions that the FDA has designated a few — MDMA and shrooms — as breakthrough therapies. Research also suggests LSD could help with depression, though the FDA hasn’t given it that same status. Thanks to their strict scheduling, research is hard to come by, but it’s progressing quickly. If you’re curious, check out our article highlighting the current studies.

Another surprising fact for many is that two of the most commonly used recreational drugs are not on any schedule at all. Both alcohol and tobacco are explicitly mentioned in the CSA and are exempt from being controlled.

Related: The War on Drugs — Why It Failed & Where to Go From Here

What The Future of Drug Scheduling in USA Looks Like

By now, you know there are five different schedules on which various drugs and other substances are listed, depending on their potential for medical use and abuse.

While having the schedules as a guiding pole concerning the use (and abuse) of controlled substances is helpful, matters surrounding drug schedules often lead to controversies.

For instance, the CSA is not always clearly worded and contains terms that need to be defined. This leads to issues of legal clarity and, in various cases, leaves lots of room for interpretation. An example is the wording “substantially similar,” which is at the core of the Federal Analog Act, a section of the CSA, but the meaning of which is nowhere defined. As the development of designer drugs becomes increasingly popular, we expect more cases will look at whether synthetic drugs are substantially similar to their controlled counterparts.

Furthermore, another interesting matter that we encourage you to follow is the debate regarding the classification of marijuana as a Schedule I drug. With President Biden’s recent initiative on the matter, we’re hopeful that changes will come in the near(er) future.