LSD for Depression: An Underrated Hallucinogen?

Shrooms and MDMA aren’t the only drugs that deserve a second chance. Will LSD join the ranks of psychedelics that are revolutionizing mental health?

We think it should.

New studies show classic psychedelics — MDMA, shrooms, and LSD — can be an incredibly effective way to treat depression, even when other methods fail. So far, the focus has been on the first two, leaving LSD in the dust.

LSD works similarly to MDMA and magic mushrooms, so it only makes sense that it could help depression the same way. How safe is it, though?

Bottom Line: Can LSD Help With Depression?

Most research so far has been on psilocybin and MDMA, but preliminary studies on LSD show a lot of promise [34]. In fact, it could prove MORE effective.

After decades of being cast out as dangerous and having no medical use, psychedelics — specifically, shrooms, ketamine, and MDMA — are suddenly a part of the “in” crowd. Extensive research is being conducted since these drugs show immense promise in treating mental illnesses like depression, PTSD, addiction, and anxiety [38,54].

Not only are the effects long-lasting with minimal use, but these drugs have a high safety profile. Shrooms and MDMA are so effective and safe that the FDA granted them breakthrough therapy status, essentially speeding up the processes needed to get them approved for use.

Ketamine clinics are popping up as psychedelic-assisted therapy causes a ‘paradigm shift’ in psychiatric research. This treatment is most often used for depressive disorders but is also effective for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), PTSD, suicide, and addiction. An analysis of nine separate trials showed a low frequency of severe side effects and positive outcomes for many patients with short-term use [33].

We’ll look at what the research shows and what it could mean for the future.

What Is LSD & How Can It Help Depression?

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide, or “acid”) is a classic hallucinogen that’s partially synthesized from ergot, a fungus in rye.

Albert Hoffman invented LSD in 1938, though somewhat unintentionally. Long story short, he was working on finding a new medicine for uterine contractions, but LSD didn’t help. He set it aside until one day, years later, he decided to experiment with it some more. A little got on his skin, and the rest is history.

By the ‘60s, LSD had made its way to the public. Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert were granted nearly unlimited access to the drug in their attempts to research it. Their studies got a little out of control, ultimately leading to the men’s dismissal from Harvard, where both taught as professors.

In 1968, the US government added LSD to its list of Schedule 1 controlled substances, ending almost all research — until now.

As of 2022, LSD is in Phase 2 of clinical trials for treating major depressive disorder. In 2021, it went through a Phase 2 trial for anxiety symptoms in severe somatic diseases or psychiatric anxiety disorders.

LSD’s Mechanism of Action (How it Works For Depression)

LSD’s effect on the brain is extensive, allowing it to help depression in multiple ways [35].

Research shows the following on LSD’s actions [36,37,38]:

- Has a strong affinity for serotonin receptors — specifically as a partial agonist of 5HT2a and an agonist of 5HT1a; it also binds to several other serotonin receptors, including 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT5A, and 5-HT6

- Modulates the ventral tegmental area, a part of the brain that contains neurons — mostly dopaminergic neurons

- Stimulates dopamine D2

- Indirectly enhances glutamatergic neurotransmission receptors; these mediate excitatory synaptic transmission in the central nervous system and regulate many processes

- Stimulates the trace amine associate receptor 1 (TAAR1), which largely regulates neurotransmission in dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin neurons in the CNS and affects the immune system

- Alters cortico-cortical and cortico-subcortical transmission

- Affects alpha-2 adrenergic receptors, stimulating the sympathetic nervous system

Right now, researchers are focused on using psilocybin (and patented analogs), but that’s mostly because it’s less controversial and has a shorter duration.

Could LSD Work Better Than Other Psychedelics?

With the world of psychedelics opening up, LSD might jump right to the top. Though shrooms, mescaline, MDMA, and DMT are classified as classic hallucinogens right alongside LSD, there are some things that set the latter apart.

LSD has a stronger binding capacity for 5-HT2A receptors than psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT. It also has a more potent bind at 5-HT1 receptors, though there are no studies yet on humans in this area. LSD is also the only serotonergic hallucinogen to bind to adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors [39].

Does this make it a more effective antidepressant? Time — and more research — will tell.

LSD’s Actions Applied in the Real World

Sure, LSD might do each one of those things, but what does that mean for those struggling with depression? How does this play out in the real world?

1. LSD Reduces Inflammation

As noted above, inflammation is thought to promote depression, and classic serotonergic psychedelics modulate the effects on immune responses. Here’s how.

LSD Lowers Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

High levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 (76,77) are associated with depression. LSD and other classic psychedelics help reduce inflammation by activating 5-HT2A receptors in immune cells, lowering the levels of these cytokines [40].

LSD also shows the ability to suppress the proliferation of B-lymphocytes and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-2, IL-4, and IL-6 [41].

LSD Alters Signaling Pathways

Classic psychedelics alter signaling pathways involved in inflammation, cellular proliferation, and cell survival via activating NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases [42].

Using classic psychedelics to activate 5-HT2A receptors can cause selective recruitment of anti-inflammatory effector pathways and disrupt or activate downstream signaling from TNF-a receptors and targets like NF-jB [40].

LSD Helps Resolve Autoimmunity Disorders

Classic psychedelics target psychosomatic origins, maladaptive chronic stress responses, inflammatory pathways, immune modulation, and enteric microbiomes, effectively helping or resolving autoimmunity disorders [41].

LSD Increases Production of Natural Killer Cells

LSD increased the number of Natural Killer cells and suppressed their production in certain doses when given to rats [41].

Fun Fact: LSD’s effect on serotonin and immunological processes opens the door for treating a variety of intractable, debilitating, and lethal disorders (including cancer and chronic infections) and could have advantages over current anti-inflammatory drugs [43].

There are fourteen known serotonin receptors, thirteen of which are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Mutations in these gene sequences are linked to several diseases. GPCRs are also involved in almost all biological processes, making them even more of a pharmacological target. In fact, about 30% of all FDA-approved medications and 65% of all prescription medications are geared towards GPCRs [40].

2. LSD Improves Mood & Life Satisfaction

Some of LSD’s effects have to do with mood — giddiness, euphoria, and more mental energy, to name a few. However, its impact is more than just a quick fix that wears off.

LSD Helps Neurocircuits

LSD can help the neuro-circuits involved in mood function better through a lengthy process that promotes neurogenesis, decreases neuroinflammation and fibrin deposition, and stabilizes glial-neuronal cross-talk [44].

LSD Changes Connections in the Brain Related to Mood

Studies show LSD helped people feel more positive, have greater empathy, and increased social behavior while improving overall relationships with others and the environment [45, 46]. Their negative emotions — fear and sadness — decreased. Even a single dose of LSD caused changes in the connectivity between parts of the brain related to positive moods.

LSD Positively Affects Cognitive Processes

In a review of fourteen studies, LSD positively affected cognitive processes, including convergent and divergent thinking and flexibility — effects that could reduce rumination [47]. Patients felt pleasant feelings and euphoria but cycled through anxiety and depressive moods.

Another study involving twenty-four people looked at the effects of three different doses of LSD (5, 10, and 20 mcg) [48]. Cognition, experience, and mood were evaluated using various tests. Most people felt an increase in their positive moods, friendliness, arousal, and fewer lapses in attention. They also felt increased confusion and anxiety, but overall, the experience benefited the majority.

Classic psychedelics induce a heightened state of consciousness and create mental flexibility that interrupts the patterns of negative and compulsive thoughts associated with depression and anxiety. Changes in attitude, perspective, values, and behavior are common — a shift sometimes referred to as an “inverse post-traumatic stress disorder-like effect.”

One of the most pronounced effects of LSD is how it enhances the reward learning rate, suggesting heightened plasticity [49]. Participants learned through reward and punishment faster with LSD, though they learned faster with rewards. Applied clinically, LSD could help change maladaptive associations.

Up to 87% of participants in clinical trials are more satisfied with their lives and experience greater overall wellbeing [50].

The effects are potent enough that many researchers advocate using them to treat end-of-life anxiety, major depression disorder, and PTSD [51].

3. LSD Promotes Spiritual Healing

LSD is considered an entheogen — a substance used to produce an altered state of consciousness for spiritual or religious purposes [52]. Users often report spiritual or mystical experiences, but, of course, these terms are subjectively defined.

Researchers have tried to dig deeper into how mindset, personality, background, and religious beliefs impact spiritual psychedelic experiences. Many people cite these trips as one of the most important occasions in their lives. Tapping into this potential could prove to be therapeutic.

So far, researchers have narrowed down two types of spiritual experiences [53]. The first has mystical characteristics; users feel special as if they’re joined or come into contact with something transcendent, ideal, or perfect. The second is more about personal growth; users experience states of insight, connection, and joy. Individuals connected to a religious ideology were more likely to have the first type. Interestingly, they did not see immediate changes but felt it was part of a life-long process.

Past trauma is prevalent among those suffering from autoimmune disorders and depression. psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy combines the benefits of psychedelics with the healing power of traditional therapy. This combination provides a greater chance of resolving these past issues and is one way this spiritual or mystical healing can come into play [41].

LSD and other psychedelics can reset the brain by destabilizing local brain networks and connectivity through neuronal avalanches, “a cascade of synchronized activity in the cortex” [43].

Hallucinogens open the mind and enhance suggestibility, allowing individuals to have a different perspective and find greater meaning. This makes it easier to change unhealthy thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. However, research suggests the therapeutic efficacy is tied to the intensity of the mystical experience [50], which draws into question just how effective microdosing actually is. More on that later.

LSD’s Safety Profile

For many people, it’s hard to get past the propaganda that’s been fed to us for decades. The War on Drugs has effectively struck fear in much of the population, but that’s about it. It’s halted nothing except much-needed research. Now that we know more, drug laws are slowly changing.

LSD’s Overall Safety

Is LSD really the dangerous drug it’s made out to be? The research says no. Classic psychedelics like ayahuasca, psilocybin, and LSD are well-tolerated, show no likelihood of physical dependence, and have low toxicity [38,54].

The general consensus after decades of research is that LSD (and similar tryptamine psychedelics) are safe and effective in a clinical setting.

Rapid and sustained therapeutic effects are noted after just a few doses — sometimes as little as a single dose. Response rates are high, and the reduction in symptoms can last for months. Medications currently used for depression require daily use and take weeks before there are any noticeable benefits. These drugs also come with severe side effects that often prevent people from continuing their treatment.

LSD’s Common Side Effects

During these studies, common side effects from LSD (beyond the hallucinations) included [50, 55]:

- Decreased attention

- Feeling cold

- Headaches

- Impaired memory

- Impaired psychomotor and intellectual functions

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Mild increase in heart rate and blood pressure

- Nausea/Vomiting

- Overestimating time intervals

- Paranoia

- Raised body temperature

- Stimulation — seen as positive and negative, depending on the person

- Transient anxiety

All side effects diminished once the drug wore off; there were no lasting impairments in performance and no cases of prolonged psychosis or neurocognitive after-effects. Adverse events were short-lived and manageable [36,56]. Less common side effects such as dissociation, paranoia, and confusion are still possible, so more research is needed to determine ways to limit the risks.

What happens if you take too much? Well, we can learn from the mistakes of others. Eight people once accidentally snorted massive doses of powdered LSD (several hundred times the standard dose), thinking it was cocaine [57]. Their plasma levels of 1000–7000 mcg per 100 mL caused them to suffer from comatose states, hyperthermia, vomiting, light gastric bleeding, and respiratory problems. The good news is they all survived and seemingly suffered no long-term damage. They learned a hard lesson that night.

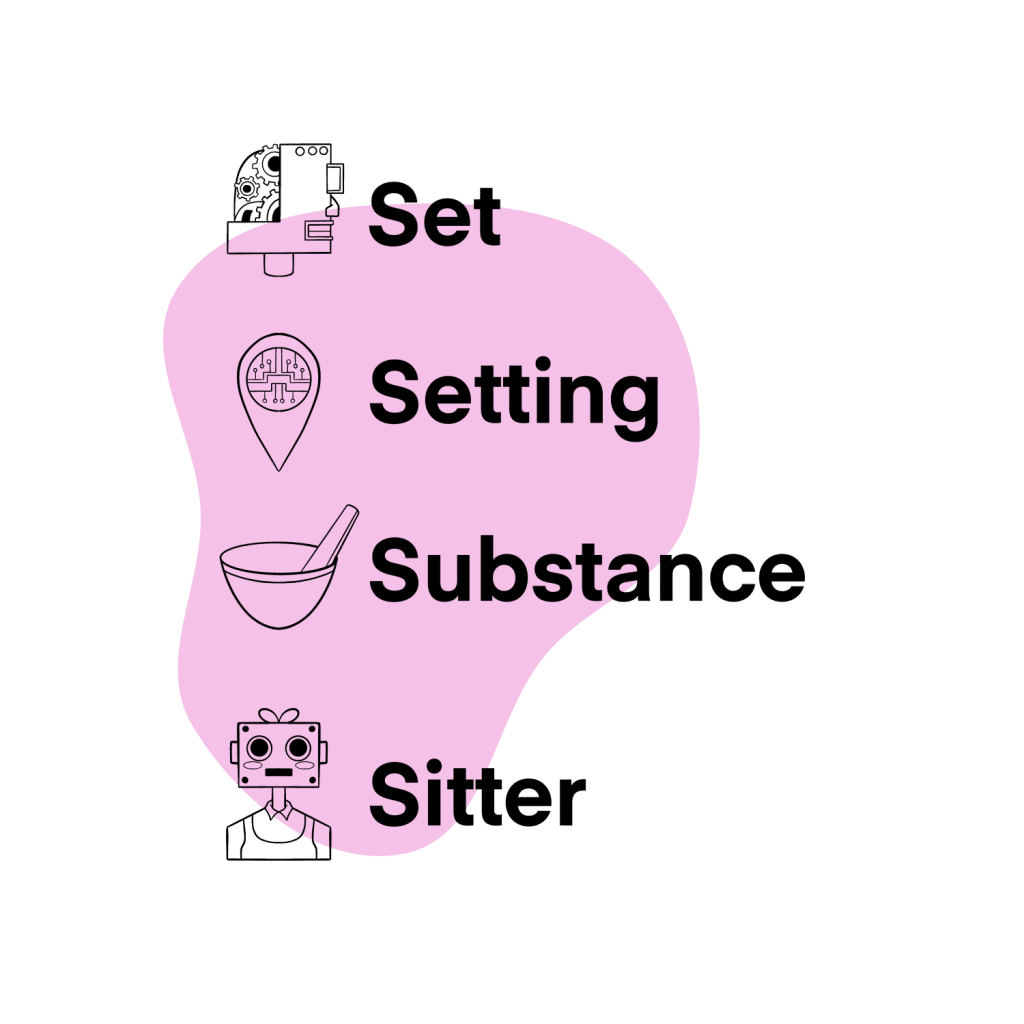

The Importance of Using LSD in a Clinical Setting

It’s important to note that the safety and effectiveness of LSD and other psychedelics largely hinges on their use in a clinical setting where the situation is controlled [46]. Outside of this, these drugs could do more harm than good if you’re not careful.

Set and setting are a large part of how well LSD works. It’s too easy for a situation to get out of control and for the trip to turn bad, which can have lasting effects on a person. Traumatic experiences (bad trips) can cause lasting damage and be a huge setback.

It’s rare, but bad trips can trigger prolonged psychoses, especially for those with a pre-existing psychotic or psychiatric disorder or if there’s a family history of them [58].

The setting includes established trust with those present and a safe and comfortable physical environment. Some study participants noted they felt more able to immerse themselves since they felt safe, and music played a prominent role in it becoming a mystical experience [59].

Basically, LSD can cause lasting effects on a person’s attitude and personality. Whether it’s positive or negative depends on what happens during the trip, so be careful.

LSD Dosage: How Much Does It Take?

Oral doses in most research cases are 100-200 mcg of LSD and are dosed by body weight. The effects appear to be dose-related, though research is somewhat contradictory.

Various research shows 100 mcg impaired recognition and recall of various stimuli and hindered performance in math, but 50 mcg did not. Some learning processes were unaffected in the 75-150 mcg range.

In one study, 26 mcg showed increased vigor but decreased positivity. Cognition and physiological functions were not affected. Much higher doses, around 100-200 mcg, showed positive effects on processing emotions, reduced reactivity to fearful things, and increased trust and openness towards others [46].

Large doses in the 200-800 mcg range reduce other psychiatric symptoms, including end-of-life anxiety, addictive disorders like alcoholism, and psychosomatic diseases. At these high levels, the positive emotional effects lasted for weeks [60].

Microdosing for Depression — Does It Work?

Microdosing — or taking about 1/10 of a normal dose (10-25 mcg of LSD) — is growing in popularity. However, most research on LSD and depression centers on larger amounts of the drug — enough to experience hallucinations to some degree. In fact, A lot of the research suggests that this “mystical experience” is a huge part of its therapeutic effects [46,51]. So far, little backs up the suggested antidepressant benefits, except for anecdotal reports. Does this mean microdosing isn’t all it’s cracked up to be?

Those who microdose often do so for the cognitive benefits — more creativity, a clearer head, and increased energy (LSD seems to be more stimulating than psilocybin) [61]. Surveys show people find other therapeutic benefits through microdosing.

Study #1

Some research shows that microdosing can cause biological changes that could be beneficial in treating depression indirectly, such as promoting cognitive flexibility [47].

One study looked at the effects of LSD on cognitive processes. It found that 10-20 mcg of LSD had subtle but positive effects on convergent and divergent thinking and the regions of the brain that deal with affective processes. Though some patients went back and forth between increased anxiety and euphoria, LSD was well-tolerated and had almost no effect on physiological measures.

However, the study did not conclude that low doses help with depression but did determine that these amounts can help decrease rumination.

Ever get stuck in your head, caught in a vicious cycle of reliving past mistakes, what could have been, or fearing the future, feeling like you can’t stop the loop as it sucks your soul into a sea of despair? That’s rumination. It’s not always so extreme, but it’s unpleasant and hard to break free from once your mind gets going.

Study #2

A 2021 study looked at the cerebral blood flow and amygdala and thalamic activity after participants took 13 mcg of LSD [62]. Researchers found LSD increased amygdala seed-based connectivity with the cerebellum and some parts of the gyrus but decreased connectivity with other parts of the gyrus. This low dose had a positive but weak impact on mood but correlated with the amygdala connection strength.

Study #3

Another study in 2022 tested the effects of 26 mcg of LSD [63]. While the patients felt the drug, it didn’t improve their mood on emotional tasks or performance on tests. Though these low doses were safe, they didn’t seem very effective in causing mood changes.

Study #4

A placebo-controlled study of healthy individuals looked at the effects of various doses of LSD [67]. Participants were given 5, 10, or 20 mcg and tested on cognition, mood, and subjective experience after six hours.

At 20 mcg, the majority felt changes in waking consciousness, including feeling more positive and friendly and fewer memory lapses but also increased anxiety and confusion.

Participants who had 5 mcg felt friendlier and aroused, with a decrease in attention lapses and anxiety.

Those who took 10 mcg noted the psychedelic-induced changes in perception.

The researchers concluded that the low doses do benefit mood and cognition, with the minimal dose starting at 5 mcg but the most pronounced effects at 20 mcg.

Study #5

Anecdotal reports are more encouraging. A recent survey showed that the users took between 6-20 mcg of LSD between two and four times a week [47]. They reported feeling more positive, fewer negative emotions, and improved relationships with others — in fact, their results were on par with what full doses do.

Study #6

Another group analyzed posts in a microdosing community on Reddit [64]. Statistically, the results seemed insignificant but descriptive statistics did indicate that average scores were high on the variables of depression, anxiety, creativity, productivity, improved mood, and overall higher quality of life.

Study #7

James Fadiman, who essentially made microdosing popular, conducted an online survey on the effects of low doses of psychedelics [65]. The study lasted 18 months and included over a thousand people from 59 countries. Participants submitted daily evaluations.

These reports showed that microdoses spaced days apart improved negative moods and increased positive moods, especially in cases of depression. Users also noted more energy, better health habits, and greater productivity. Shockingly enough, they also had a decrease in symptoms from other health issues, such as migraines, PMS, shingles, traumatic brain injury, and other conditions that aren’t linked with psychedelic use.

Is this the placebo effect at work, are we missing some other piece of the puzzle, or will more research come to this conclusion? It’s safe to say the reason for the marked improvement doesn’t matter. Many people find relief from depression through microdosing — period.

Are Repeated Microdoses of LSD Safe?

While larger amounts of a psychedelic can have a long-term impact on depression, microdosing works differently. We’ll get into how to microdose in more detail below, but it requires small amounts every few days, leaving many people wondering if this practice is safe.

Though the therapeutic value is in question, studies show microdosing is safe for repeated use. One study cites a threshold dose of 13 mcg [46, 47].

How to Microdose LSD

The average microdose for LSD is 8-12 mcg. Always start with a low amount and see how you feel. Until you know how you’ll react, make sure you practice standard safety measures for tripping. Have a trip sitter, be in a safe location, and only do it when you have a good mindset. Always test any drug you use.

Before you jump in, figure out what your intentions are. What are you hoping to accomplish? Is there a specific goal you’re aiming for? Journaling is a great way to figure things out or learn something new.

Next, come up with a dosing schedule. Get into the habit of taking your dose at the same time every day. There are a few different schedules to try. Some people dose five days on, two days off, or dose one week and take a break for a week. Dr. James Fadiman, the father of microdosing, came up with a schedule that calls for dosing on day one, resting on days two and three, and repeating. Test out all three if you want. Just make notes of the effects for each dose and of any ongoing progress you feel (or don’t feel).

Understanding Depression & Its Link to LSD

It’s been long understood that depression is caused by improper functioning of monoaminergic neurotransmitters — think serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine receptors [1, 2].

The serotonergic system helps regulate emotional behavior. Depressed and suicidal patients have increased cortical 5-HT2A receptor expression [66]. Antidepressants work by reducing this receptor’s density.

Serotonin is also involved in inhibiting activity in the amygdala. Hyperactivity in the amygdala is linked to symptoms of depression.

However, this is an incomplete picture of what’s going on, and now, neuroplasticity processes — or functional and structural changes — in response to the environment and experience are implicated as well [1].

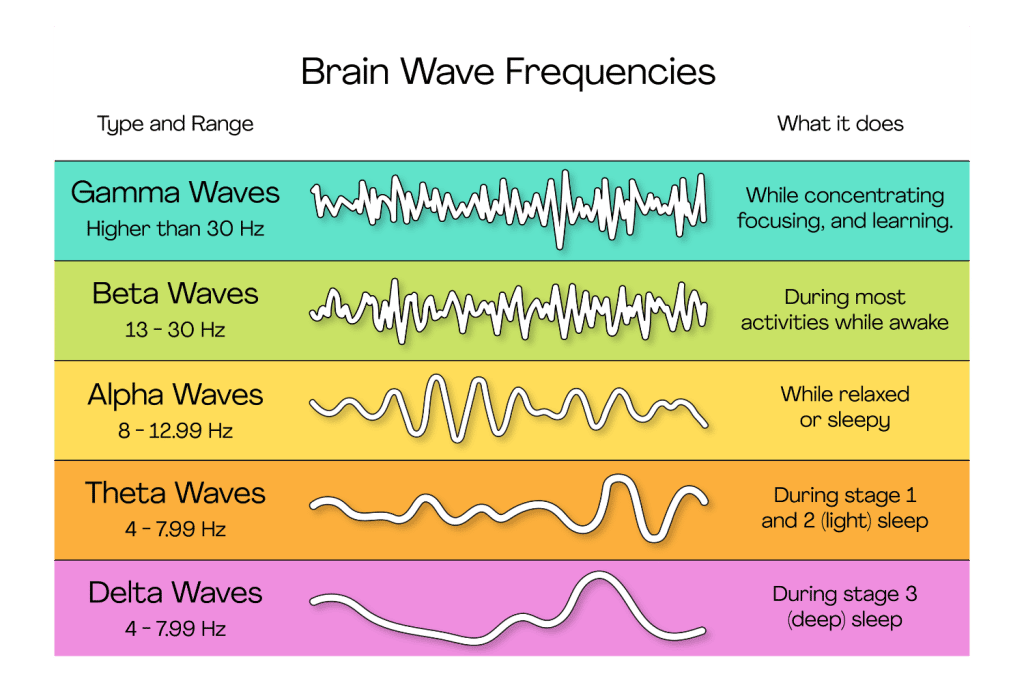

Studies show depression affects brain activity in almost the whole cerebral cortex [3, 4]. It causes oscillating patterns in all frequencies — delta, theta, beta, and alpha — but alpha is affected significantly less so.

Think of brain frequencies as the gear it’s running in:

- Delta is the lowest frequency and occurs in a deep sleep and some abnormal processes.

- Theta is slow activity connected to creativity, intuition, daydreaming, memories, and emotions but is particularly strong during meditation and focus.

- Alpha is tied to mental coordination and resourcefulness. It’s considered the dominant frequency and what you’re most likely using when listening or thinking.

- Gamma is the only frequency in every part of the brain and works when the brain is processing information from different areas at the same time.

This vast impact means depression manifests in different ways, and there are numerous types, including:

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Persistent depressive disorder

- Postpartum depression

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Psychotic depression

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

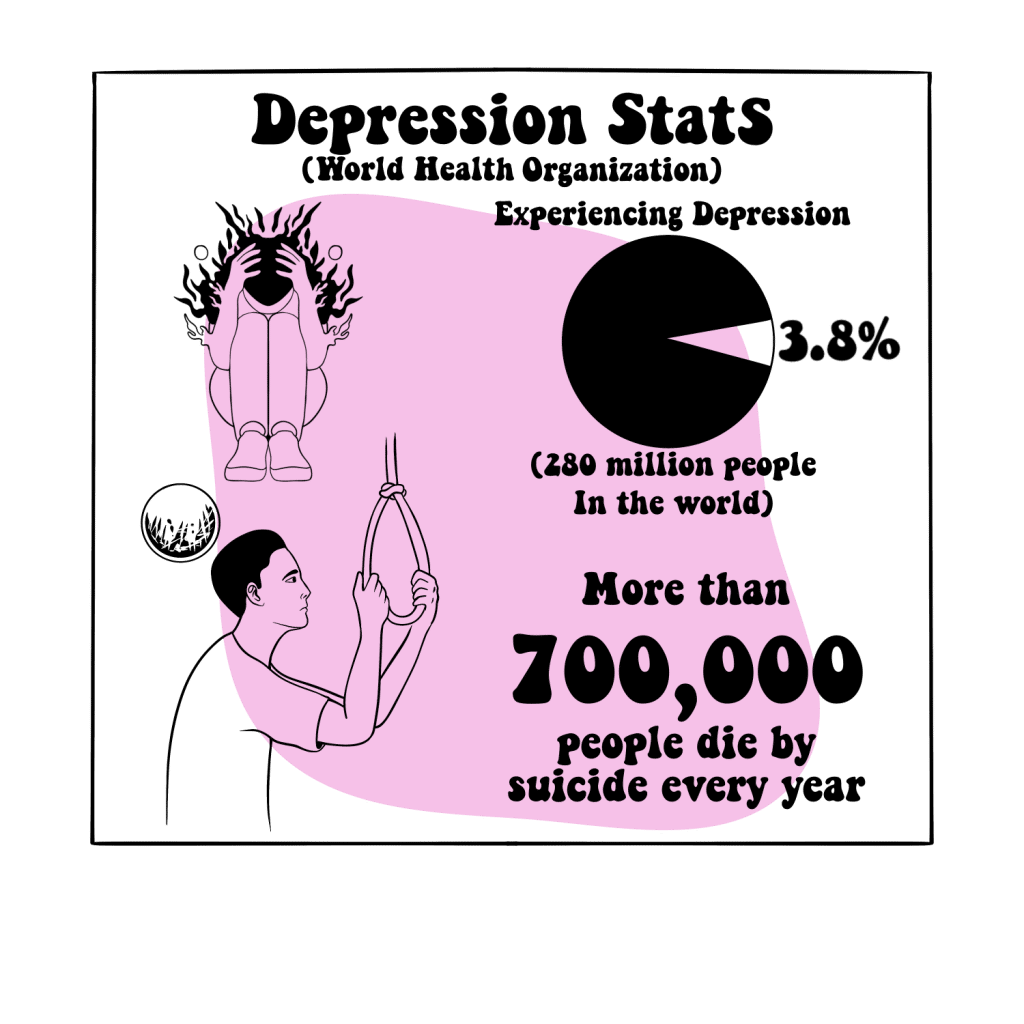

Depression Stats

Despite all we know bout depression and the plethora of medications and therapies available, the numbers are not dropping. One would expect an improvement, but instead, we see the opposite happening — depression cases are skyrocketing.

The World Health Organization says 3.8% (about 280 million) of the world’s population is affected, and over 700,000 people die from suicide each year. It’s the fourth most common cause of death in 15-29 year-olds.

Why? There are a few possible explanations.

- Misdiagnoses

- Iatronergic consequences

- Treatments are less effective than the research suggests

- Trial efficacy doesn’t translate to the real world

Unfortunately, there’s strong evidence supporting the last two — 30% of those diagnosed are resistant to standard treatments [5,6]. The situation would be simpler to solve if it was a matter of misdiagnoses.

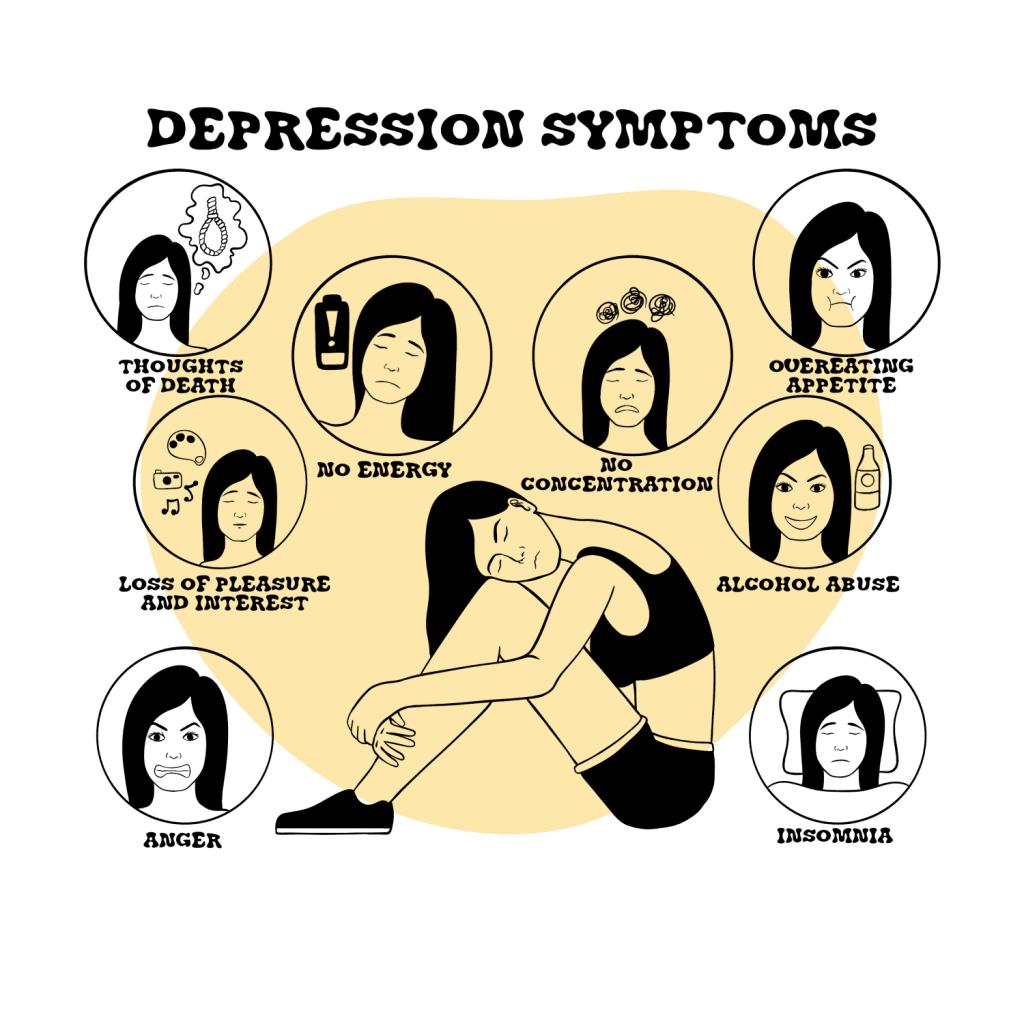

Depression Symptoms

Considering how widespread the problem is, it’s important to know what depression looks like — for yourself and others. If you see someone that might be struggling or are dealing with it yourself, get help!

Depression is more than “feeling sad” and not something a person has control over. Even extreme grief doesn’t resemble depression; grief brings waves of sadness, but self-esteem doesn’t change. Depression causes a consistently low mood and self-loathing.

Symptoms of depression vary and can be mild or severe, though they must last at least two weeks and differ from the typical levels of functioning for a diagnosis.

Depression can cause the following, though not all of these symptoms need to be present:

- Feeling sad, hopeless, empty, worthless, guilty

- Focus on past failures

- Loss of interest and pleasure in things once enjoyed

- Appetite changes, such as increased cravings or inability to eat

- Weight gain or loss

- Decreased energy and fatigue

- Increased “nervous” activity, such as wringing hands, pacing, etc.

- Agitation, irritability

- Difficulty concentrating and making decisions

- Slowed speech and movements

- Thoughts of suicide and death

- Unexplained physical symptoms, such as headaches or back pain

- Sleep problems, such as sleeping too much or too little

- Angry outbursts

Recognizing Depression in Children & Teens

While the signs of depression are similar regardless of age, there are some specific symptoms to watch for in children and teens, along with the previously mentioned ones.

- Anger, irritability

- Avoiding social interactions

- Clinginess

- Drug and alcohol use

- Extremely sensitive and feeling misunderstood

- Overly negative attitude

- Poor grades and performance in school

- Refusing to go to school

- Self-harm

- Unexplained aches and pains

- Worry

If you have teens, you probably read that list and roll your eyes because you recognize at least half of those in your kid on a good day. Teens are notoriously moody, irritable, antisocial (around family), and often hate school — not all of them, but it’s a stereotype for a reason. Some of it’s normal and you can write it off as hormonal and life situations. Just be aware of extremes or sudden changes.

Recognizing Depression in Older Adults

Again, older adults will show the usual signs of depression, but there are other symptoms that are often overlooked, causing it to be under or misdiagnosed.

Seek help if you notice any signs of depression, including the following:

- Avoiding social interactions

- Memory problems

- Personality changes

- Physical aches and pains

What Causes Depression?

You know what depression looks like and how it works, but what causes it? Generally, depression is caused by trauma, genetics, illness, or medication. The latter two are pretty straightforward, but trauma’s effect on the mind is not fully understood.

Trauma, Stress, & Major Life Changes

It seems obvious that any major upheaval or trauma can cause depression. There’s a strong connection between childhood trauma, suicidal behavior, and treatment-resistant depression [7].

However, it goes deeper than a “my-life-sucks-and-I-hate-everything” issue.

Studies suggest trauma is associated with neuroendocrine stress response sensitization, immune activation, glucocorticoid activation, increased CRF activity, and reduced hippocampal volume — some of which are features of depression [8]. These neuroendocrine changes possibly show an increased risk of stress-induced depression.

Adverse childhood experiences are also linked to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [9].

Other studies suggest that deficits in cognitive control — specifically the inability to stop or disengage from negative memories — increase unhealthy emotional regulation and contribute to negative biases in long-term memory [10]. This ultimately makes the negative mood associated with depression worse and lasts longer.

Gabor Mate is just one example of a modern psychologist that believes trauma can cause depression, addiction, and other disorders, and that healing comes once you get to the root of it.

Genetics

Researchers understand genetics can be a cause of depression but have been unable to pin down exactly how.

Until recently, they weren’t sure it was possible. Depression shows up in more than 10,000 ways based on symptom profiles and was described as “an entangled web of partly overlapping biopsychosocial constructs, with overlapping genetic contributions and underlying biological mechanisms” [11].

In layman’s terms, there are so many subtypes, biological pathways, and environmental factors, that it’s hard to weed through everything and pinpoint the genetic causes.

Various methods have been used — analyzing candidate genes and genome-wide association analysis and sequencing — and a large number of links between genes and depression have been discovered but are unconfirmed [12].

Physical Illness

Many health issues can cause depression — living with chronic pain or illness problems can interfere with life and can sink many people into a pit [13,14]. Often, it’s the constant physical pain, increased life difficulties, or side effects from medications that bring on severe depression. Other times, it’s biological factors.

Fibromyalgia, migraines, and irritable bowel syndrome are often tied to depression, but other common ones include [15,16]:

- Cancer

- Chronic fatigue

- Chronic pain

- Heart disease

- Stroke

Unfortunately, this greatly reduces the treatment’s effectiveness. Data from the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service in the UK shows patients suffering from a long-term health condition demonstrate poorer outcomes when treating depression [17].

Research also shows chronic illness impacts more than just the patient’s mental health — their family members show higher rates of depression and other mental health problems [18,19].

Inflammation

While inflammation technically falls under the “physical illness” category, it warrants its own section. However, it’s important to note there’s a very strong link between stress, trauma, disease (including gut dysbiosis and chronic infections), inflammation, and depression.

Inflammation is increasingly linked to treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [20]. Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and TRD have elevated C-reactive protein and cytokine levels, a sign of inflammation [6].

As such, inflammatory biomarkers could be a tool for diagnosing, treating, and developing interventions for depression.

Immune system dysregulation also causes irregularities in the kynurenine pathway [21]. When it functions properly, the pathway turns tryptophan into serotonin and melatonin. However, inflammation causes excessive indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). This enzyme catabolizes tryptophan into kynurenine (KYN), a neurotoxic substrate that can cause neurodegenerative diseases. These actions decrease the tryptophan available for producing serotonin, which is linked to the cause of depression.

Autoimmune mechanisms or dysregulated inflammatory cytokine loops could cause depression and anxiety symptoms.

Medications

Sometimes medication is to blame for depression, and sometimes it’s the disease. Or, it could be entirely unrelated. Because of the lack of evidence, it’s hard to say for certain if a medicine causes depression or if it’s coincidental.

However, there are a handful linked to depression and should be used with caution [22]:

- Barbiturates

- Corticosteroids

- Efavirenz

- Flunarizine

- Interferon-α

- Mefloquine

- Topiramate

- Vigabatrin

Interestingly, it becomes somewhat of a “what came first” scenario [23]. Depression causes physical pain — usually in the form of stomach issues and headaches — but these diseases impact people’s lives and cause depression as well [24].

If you feel a medication is impacting your mental health, speak to your doctor immediately.

Common Treatments for Depression

Oddly, some of the better treatments for depression are underutilized. We’ll take a look at what’s usually used, along with some less-popular methods and what’s up-and-coming.

Medication

Prescription antidepressants are the most common form of treatment, though the effectiveness varies and many patients stop taking their medication before they should. Studies found about 28% discontinue treatment within one month and 44% stop within three months [25]. This increases the risk for suicide and its chronic tendencies.

For those that do not respond to antidepressants, switching drugs or combining them with other methods is necessary.

The following are standard antidepressant drugs:

- Atypical Antidepressants

- Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

- N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) Antagonists

- Neuroactive Steroid Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)-A Receptor-Positive Modulators

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI)

- Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRI)

- Tricyclic and Tetracyclic Antidepressants

These medications come with a host of negative side effects — including some serious ones — such as nausea, fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and suicide.

It’s important to never stop taking an antidepressant without consulting with a doctor. Suicidal ideation is common in the first few weeks of treatment and when abruptly stopped.

Lithium

Lithium is a mood stabilizer used most often for bipolar, though it’s still used somewhat for depression. It used to be more common, and should probably be used more than it is. Studies show it reduces the risk of suicide and relapse and can decrease aggression and impulsivity — both are possible antisuicidal effects [26].

It’s important to note that lithium has a strong likelihood of interacting with serotonergic psychedelics. This substance is a contraindication for psychedelic therapy.

Triiodothyronine (T3)

Triiodothyronine is the active form of thyroxine, the primary thyroid hormone. T3 shows the ability to increase response rates and lower depression severity scores in some people [27]. Adding T3 to other medications could increase their effectiveness.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

ECT is high-frequency electrical pulses sent to a specific part of the brain, causing pyramidal cell firing with generalized cortical activity and a tonic-clonic seizure.

Yes, shock therapy. And, much as one could expect, it’s not implemented much because of the stigma attached to it. The thought is terrifying to most people, but it’s actually very effective (Could’ve said “shockingly,” but didn’t. You’re welcome). More so than standard antidepressants, in fact [28].

Some studies show over half of the patients that did not respond to at least one antidepressant medication showed improvement with ECT within the first week [6].

Higher doses are more effective than lower doses. This process is typically done a few times a week, in 6-18 sessions.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy are three types of psychotherapy used for depression.

All of these methods of intervention show a significant decrease in symptoms of depression compared to standard care [29].

Therapy can work alone or in conjunction with other methods. Antidepressants are the first step, but psychotherapy is often the go-to when medications don’t work [30].

Novel Treatments

The increase in depression shows a very real need for novel treatments — things beyond the typical medications that don’t seem to be working well enough [31]. So far, one of the most promising is psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, which amps up traditional psychotherapy with the use of psychedelics. Coupled with antidepressants, this form of therapy could be the answer when other treatments fail [32].

Other new kinds of therapy include:

- Memory Specificity Training (MEST)

- Multimodal antidepressants

- Neural modulation techniques (transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and deep brain stimulation)

- Neutraceuticals

- Opioids

- Psychedelics

Other Ways to Help Depression

Depression isn’t something that’s easily cured, but there are ways to improve your life and help boost whatever treatment you use.

- Don’t expect immediate improvement

- Don’t make important decisions until you feel better

- Educate yourself about depression

- Exercise, moderate levels of activity

- Have a close friend to confide in

- Set realistic goals

- Spend time with people (don’t scoff; it really can help)

Final Thoughts: More Work is Needed, But LSD Appears Highly Affective For Depressive Disorders

With the depression and suicide numbers climbing, it’s obvious we need something new — and drastic — to help. All other measures have failed to help people in any permanent and meaningful way. We’re on the verge of a huge shift — legally, medically, and mentally. Once we loosen the harsh restrictions on these very promising drugs, we can move forward as a society.

LSD — and other psychedelics — have the potential to treat depression in a way we haven’t seen before. We just need to get past the biggest hurdle — the stigma. And the hallucinations. Of course, that’s not an issue for everyone. Some people enjoy them.

References

- Benarroch, E. E. (2021). Neuroscience for Clinicians: Basic Processes, Circuits, Disease Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Implications. Oxford University Press.

- Christoph, G. R., Kuhn, D. M., & Jacobs, B. L. (1977). Electrophysiological evidence for a dopaminergic action of LSD: depression of unit activity in the substantia nigra of the rat. Life Sciences, 21(11), 1585-1596.

- Peng, H., Xia, C., Wang, Z., Zhu, J., Zhang, X., Sun, S., … & Li, X. (2019). Multivariate pattern analysis of EEG-based functional connectivity: A study on the identification of depression. IEEE Access, 7, 92630-92641.

- Fingelkurts, A. A., & Fingelkurts, A. A. (2015). Altered structure of dynamic electroencephalogram oscillatory pattern in major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 77(12), 1050-1060.

- Ormel, J., Hollon, S. D., Kessler, R. C., Cuijpers, P., & Monroe, S. M. (2022). More treatment but no less depression: The treatment-prevalence paradox. Clinical Psychology Review, 91, 102111.

- Voineskos, D., Daskalakis, Z. J., & Blumberger, D. M. (2020). Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 16, 221.

- Yrondi, A., Vaiva, G., Walter, M., Amato, T. D., Bellivier, F., Bennabi, D., … & Horn, M. (2021). Childhood Trauma increases suicidal behaviour in a treatment-resistant depression population: A FACE-DR report. Journal of psychiatric research, 135, 20-27.

- Heim, C., Newport, D. J., Mletzko, T., Miller, A. H., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2008). The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(6), 693-710.

- Morris, G., Berk, M., Maes, M., Carvalho, A. F., & Puri, B. K. (2019). Socioeconomic deprivation, adverse childhood experiences and medical disorders in adulthood: mechanisms and associations. Molecular neurobiology, 56(8), 5866-5890.

- LeMoult, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2019). Depression: A cognitive perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 69, 51-66.

- Cai, N., Choi, K. W., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Reviewing the genetics of heterogeneity in depression: operationalizations, manifestations and etiologies. Human molecular genetics, 29(R1), R10-R18.

- Shadrina, M., Bondarenko, E. A., & Slominsky, P. A. (2018). Genetics factors in major depression disease. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, 334.

- Clarke, D. M., & Currie, K. C. (2009). Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Medical Journal of Australia, 190, S54-S60.

- Kang, H. J., Kim, S. Y., Bae, K. Y., Kim, S. W., Shin, I. S., Yoon, J. S., & Kim, J. M. (2015). Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: research and clinical implications. Chonnam medical journal, 51(1), 8-18.

- Bruti, G., Magnotti, M. C., & Iannetti, G. (2012). Migraine and depression: bidirectional co-morbidities?. Neurological Sciences, 33(1), 107-109.

- Goodwin, G. M. (2022). Depression and associated physical diseases and symptoms. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience.

- Seaton, N., Moss-Morris, R., Norton, S., Hulme, K., & Hudson, J. (2022). Mental health outcomes in patients with a long-term condition: analysis of an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service. BJPsych Open, 8(4).

- Incledon, E., Williams, L., Hazell, T., Heard, T. R., Flowers, A., & Hiscock, H. (2015). A review of factors associated with mental health in siblings of children with chronic illness. Journal of Child Health Care, 19(2), 182-194.

- Holmes, A. M., & Deb, P. (2003). The effect of chronic illness on the psychological health of family members. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 6(1), 13-22.

- Strawbridge, R., Arnone, D., Danese, A., Papadopoulos, A., Vives, A. H., & Cleare, A. J. (2015). Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: a meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(10), 1532-1543.

- Gałecki, P., & Talarowska, M. (2018). Inflammatory theory of depression. Psychiatr Pol, 52(3), 437-447.

- Celano, C. M., Freudenreich, O., Fernandez-Robles, C., Stern, T. A., Caro, M. A., & Huffman, J. C. (2022). Depressogenic effects of medications: a review. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience.

- Gold, S. M., Köhler-Forsberg, O., Moss-Morris, R., Mehnert, A., Miranda, J. J., Bullinger, M., … & Otte, C. (2020). Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 6(1), 1-22.

- IsHak, Waguih William MD; Wen, Raymond Y. BS; Naghdechi, Lancer DO; Vanle, Brigitte PhD; Dang, Jonathan MD; Knosp, Michelle DO; Dascal, Julieta BA; Marcia, Lobsang BS; Gohar, Yasmine BA; Eskander, Lidia MD; Yadegar, Justin MS; Hanna, Sophia BS; Sadek, Antonious MD; Aguilar-Hernandez, Leslie BA; Danovitch, Itai MD; Louy, Charles MD, PhD Pain and Depression: A Systematic Review, Harvard Review of Psychiatry: 11/12 2018 – Volume 26 – Issue 6 – p 352-363

- Jung, W. Y., Jang, S. H., Kim, S. G., Jae, Y. M., Kong, B. G., Kim, H. C., … & Kim, C. R. (2016). Times to discontinue antidepressants over 6 months in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Investigation, 13(4), 440.

- Cipriani, A., Hawton, K., Stockton, S., & Geddes, J. R. (2013). Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 346.

- Aronson, R., Offman, H. J., Joffe, R. T., & Naylor, C. D. (1996). Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression: a meta-analysis. Archives of general psychiatry, 53(9), 842-848.

- The, U. K. (2003). Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 361(9360), 799-808.

- Health Quality Ontario. (2017). Psychotherapy for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: a health technology assessment. Ontario health technology assessment series, 17(15), 1.

- Ijaz, S., Davies, P., Williams, C. J., Kessler, D., Lewis, G., & Wiles, N. (2018). Psychological therapies for treatment‐resistant depression in adults. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (5).

- Ceskova, E., & Silhan, P. (2018). Novel treatment options in depression and psychosis. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 14, 741.

- Greenway, K. T., Garel, N., Jerome, L., & Feduccia, A. A. (2020). Integrating psychotherapy and psychopharmacology: psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and other combined treatments. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 13(6), 655-670.

- Schenberg, E. E. (2018). Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a paradigm shift in psychiatric research and development. Frontiers in pharmacology, 9, 733.

- Reiff, C. M., Richman, E. E., Nemeroff, C. B., Carpenter, L. L., Widge, A. S., Rodriguez, C. I., … & Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments, a Division of the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research. (2020). Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 391-410.

- Christoph, G. R., Kuhn, D. M., & Jacobs, B. L. (1977). Electrophysiological evidence for a dopaminergic action of LSD: depression of unit activity in the substantia nigra of the rat. Life Sciences, 21(11), 1585-1596.

- Passie, T., Halpern, J. H., Stichtenoth, D. O., Emrich, H. M., & Hintzen, A. (2008). The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 14(4), 295-314.

- De Gregorio, D., Comai, S., Posa, L., & Gobbi, G. (2016). d-Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) as a model of psychosis: mechanism of action and pharmacology. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(11), 1953.

- Więckiewicz, G., Stokłosa, I., Piegza, M., Gorczyca, P., & Pudlo, R. (2021). Lysergic acid diethylamide, psilocybin and dimethyltryptamine in depression treatment: a systematic review. Pharmaceuticals, 14(8), 793.

- Liechti, M. E. (2017). Modern clinical research on LSD. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2114-2127.

- Flanagan, T. W., & Nichols, C. D. (2018). Psychedelics as anti-inflammatory agents. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(4), 363-375.

- Thompson, C., & Szabo, A. (2020). Psychedelics as a novel approach to treating autoimmune conditions. Immunology letters, 228, 45-54.

- Szabo, A. (2015). Psychedelics and immunomodulation: novel approaches and therapeutic opportunities. Frontiers in immunology, 6, 358.

- Nichols, D. E., Johnson, M. W., & Nichols, C. D. (2017). Psychedelics as medicines: an emerging new paradigm. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 101(2), 209-219.

- Idell, R. D., Florova, G., Komissarov, A. A., Shetty, S., Girard, R. B. S., & Idell, S. (2017). The fibrinolytic system: a new target for treatment of depression with psychedelics. Medical Hypotheses, 100, 46-53.

- Markopoulos, A., Inserra, A., De Gregorio, D., & Gobbi, G. (2021). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) promotes social behaviour through 5-HT2A and ampa in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). European Psychiatry, 64(S1), S416-S417.

- Bershad, A. K., Schepers, S. T., Bremmer, M. P., Lee, R., & de Wit, H. (2019). Acute subjective and behavioral effects of microdoses of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy human volunteers. Biological psychiatry, 86(10), 792-800.

- Kuypers, K. P. (2020). The therapeutic potential of microdosing psychedelics in depression. Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology, 10, 2045125320950567.

- Hutten, N. R., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., Theunissen, E. L., Holze, F., Liechti, M. E., … & Kuypers, K. P. (2020). Mood and cognition after administration of low LSD doses in healthy volunteers: A placebo-controlled dose-effect finding study. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 81-91.

- Kanen, J. W., Luo, Q., Kandroodi, M. R., Cardinal, R. N., Robbins, T. W., Carhart-Harris, R. L., & den Ouden, H. E. (2021). Effect of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) on reinforcement learning in humans. bioRxiv, 2020-12.

- Muttoni, S., Ardissino, M., & John, C. (2019). Classical psychedelics for the treatment of depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 258, 11-24.

- Dos Santos, R. G., Bouso, J. C., & Hallak, J. E. (2019). Serotonergic hallucinogens/psychedelics could be promising treatments for depressive and anxiety disorders in end-stage cancer. BMC psychiatry, 19(1), 1-4.

- Cole‐Turner, R. (2014). ENTHEOGENS, MYSTICISM, AND NEUROSCIENCE: with Ron Cole‐Turner,“Entheogens, Mysticism, and Neuroscience”; William A. Richards,“Here and Now: Discovering the Sacred with Entheogens”; G. William Barnard,“Entheogens in a Religious Context: The Case of the Santo Daime Religious Tradition”; and Leonard Hummel,“By Its Fruits? Mystical and Visionary States of Consciousness Occasioned by Entheogens.”. Zygon®, 49(3), 642-651.

- Johnstad, P. G. (2020). Entheogenic experience and spirituality. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, 33(5), 463-481.

- Andersen, K. A., Carhart‐Harris, R., Nutt, D. J., & Erritzoe, D. (2021). Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern‐era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(2), 101-118.

- Holze, F., Caluori, T. V., Vizeli, P., & Liechti, M. E. (2022). Safety pharmacology of acute LSD administration in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1893-1905.

- Rossi, G. N., Hallak, J. E., Bouso Saiz, J. C., & Dos Santos, R. G. (2022). Safety issues of psilocybin and LSD as potential rapid acting antidepressants and potential challenges. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 1-16.

- Klock, J. C., Boerner, U., & Becker, C. E. (1974). Coma, hyperthermia and bleeding associated with massive LSD overdose: a report of eight cases. Western Journal of Medicine, 120(3), 183.

- Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2008). Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. Journal of psychopharmacology, 22(6), 603-620.

- Hendricks, P. S., Copes, H., Family, N., Williams, L. T., Luke, D., & Raz, S. (2022). Perceptions of safety, subjective effects, and beliefs about the clinical utility of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy participants within a novel intervention paradigm: Qualitative Results from a proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(3), 337-347.

- Fuentes, J. J., Fonseca, F., Elices, M., Farré, M., & Torrens, M. (2020). Therapeutic use of LSD in psychiatry: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Frontiers in psychiatry, 943.

- Johnstad, P. G. (2018). Powerful substances in tiny amounts: an interview study of psychedelic microdosing. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 35(1), 39-51.

- Bershad, A. K., Preller, K. H., Lee, R., Keedy, S., Wren-Jarvis, J., Bremmer, M. P., & de Wit, H. (2020). Preliminary report on the effects of a low dose of LSD on resting-state amygdala functional connectivity. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 5(4), 461-467.

- de Wit, H., Molla, H. M., Bershad, A., Bremmer, M., & Lee, R. (2022). Repeated low doses of LSD in healthy adults: A placebo‐controlled, dose-response study. Addiction Biology, 27(2), e13143.

- Miura, K. K. (2022). Cognitive, Mental Health, and Physiological Outcomes of Psychedelic Microdosing: A Quantitative Content Analysis of Reddit’s Microdosing Community (Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado Colorado Springs).

- Fadiman, J., & Korb, S. (2019). Might microdosing psychedelics be safe and beneficial? An initial exploration. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 51(2), 118-122.

- Pandey, G. N., Dwivedi, Y., Rizavi, H. S., Ren, X., Pandey, S. C., Pesold, C., … & Tamminga, C. A. (2002). Higher expression of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the postmortem brains of teenage suicide victims. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(3), 419-429.

- Hutten, N. R., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., Theunissen, E. L., Holze, F., Liechti, M. E., … & Kuypers, K. P. (2020). Mood and cognition after administration of low LSD doses in healthy volunteers: A placebo-controlled dose-effect finding study. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 81-91.