R. Gordon Wasson: A Pioneer in the Psychedelic Revolution

Robert Gordon Wasson was a catalyzing figure in the psychedelic revolution — but he also caused some harm along the way.

R. (Robert) Gordon Wasson is considered by many as the godfather of the psychedelic revolution.

He was a legendary mushroom expert and the first person to bring psilocybin-containing mushrooms into the public eye.

Wasson released several papers looking at psychedelic mushrooms and the place of fungi in ancient cultures and religions. He was the main reason people began flocking to Oaxaca, Mexico, to consume magic mushrooms with Maria Sabina — the mother of mushrooms.

He’s known by the Mazatec as “the first white man in history to eat the divine mushrooms.” If it wasn’t for Wasson, who knows how long it would have taken the western world to discover, understand, and appreciate the importance of psychedelic fungi.

In this article, we’ll be looking into the following:

- Robert Gordon Wasson’s life

- His introduction to mushrooms

- How he became an ethnomycologist

- His travels in Mexico

- His meeting with Maria Sabina

- His work in the field of psychedelics

- How Wasson has impacted the world of psychedelics

We’ll also look at the literature Robert Gordan Wasson has produced, as well as some of his research papers and most famous quotes.

Who Was R. Gordon Wasson?

R. Gordon Wasson was born on September 22, 1898, in Montana. He was an ethnomycologist, author, seasoned explorer, and the Vice President for Public Relations at J.P. Morgan and Co.

Wasson was part of several pieces of groundbreaking research in the fields of botany, ethnobotany, and anthropology. The CIA even funded his research in the late 50s. He is an immortal figure within the psychedelic community thanks to his research into psychedelic fungi and is an important symbol against the stigmatization of natural psychedelics.

R. Gordon Wasson was a pioneer in the psychedelic revolution. He was the person that brought psilocybin-containing mushrooms to the public eye and the one to inspire other pioneers to go out in search of mystical experiences and psychedelic fungi.

Wasson discovered links between the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms and religion by unearthing evidence of psychedelic mushroom use in cultures spread throughout the world, from Europe to Mexico.

He influenced several other famous people in the psychedelic world and sparked a flame so strong in some that they, too, became pioneers in the field. Dennis and Terence McKenna, Alexander Shulgin, Aldous Huxley, and Timothy Leary are just a few of the big names that Wasson inspired.

If it wasn’t for Wasson, many of the legendary pioneers in psychedelics might not have produced the work that they did.

Wasson studied at the Columbia School of Journalism and the London School of Economics after he received the first Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship. He taught English at Columbia University for a year and then became a reporter for the New Haven Register.

He lived in New York for many years and worked with the New York Herald Tribune writing a column on financial news weekly. He then joined J.P Morgan, where he pioneered the field of banking public relations as Vice President — all before he became known for his travels and studies surrounding mystical fungi.

He was introduced to wild edible mushrooms (non-psychedelic) variety by his wife, Valentina Pavlovna Guercken. Before this, Wasson, like many Americans at the time, assumed that wild mushrooms were dangerous and potentially poisonous — having “mycophobia.”

This distorted view of mushrooms would soon change, and Robert Gordon Wasson’s life would become dedicated to the intriguing world of fungi. Let’s take a look into the life of R. Gordon Wasson and how he went from a successful banker to a pioneer of the psychedelic revolution.

What Was R. Gordon Wasson Most Famous For?

Wasson is most famous for his research into magic mushrooms, at least among the psychedelic community.

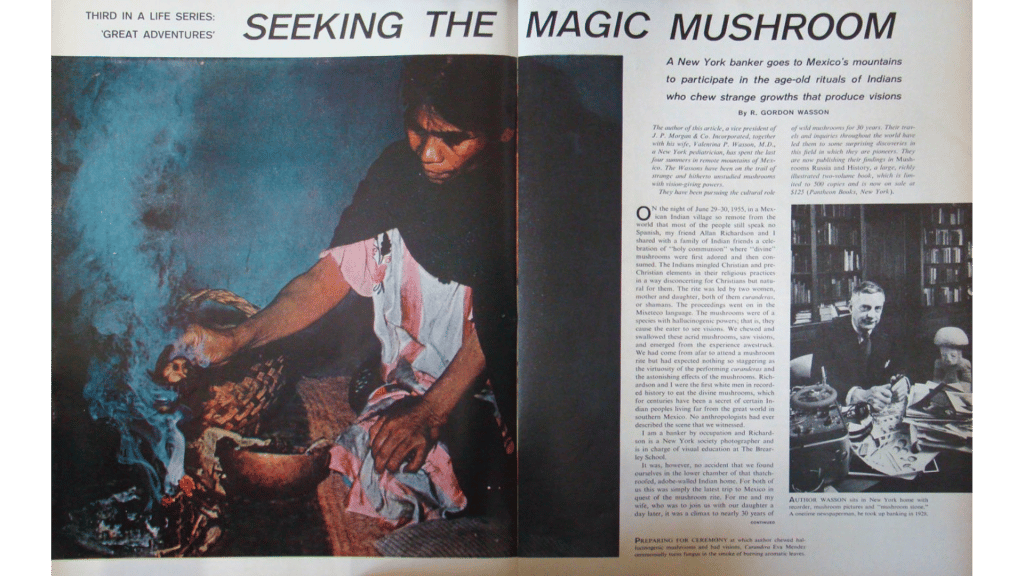

Perhaps the first thing most people think of when they hear the name Robert Gordon Wasson is his 1957 article in LIFE Magazine. In the article titled “Seeking The Magic Mushroom,” Wasson wrote of his experience with the curandera Maria Sabina when he traveled to Huautla de Jiménez to partake in one of her mushroom ceremonies.

After this article went “viral,” psilocybin and the magic mushroom became widely known. This single article tipped the first domino in a chain that triggered the psychedelic revolution of the 60s.

The Life of Robert Gordon Wasson

The life of Robert Gordon Wasson was an interesting one, to say the least. He knew very little about mushrooms before he was introduced to them. He’d call wild mushrooms “putrid” and label them poisonous.

His lack of knowledge in the field of fungi soon changed when he met his wife. She appreciated the foods of the forest, having learned how to forage many different species during her early life in Russia.

Wasson’s views on mushrooms changed when he was in his early 30s on his honeymoon. It wasn’t until this stage in his life that he began researching mushrooms and exploring, searching for psychedelic fungi and mushroom use in cultures and religions. So what did R. Gordon Wasson do for the 30 years prior?

The Early Life of R. Gordon Wasson

Robert Gordon Wasson was born in Great Falls, Montana, in 1898. His early years were spent in Newark, New Jersey, where he attended public school.

At 16, Wasson made an unaccompanied trip to Europe for over a year. He spent much of his time in France and Spain, learning both languages fluently before traveling home.

In 1917, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as a private for 14 months. When he returned to civilian life from the Expeditionary Forces, Wasson enrolled at the Columbia School of Journalism. He graduated in 1920 and received the first-ever Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship.

This award allowed him to study overseas. Robert chose to study at the London School of Economics in England. During his time there, he traveled to the continent to explore other parts of Europe. In the spring of 1921, he headed over to Greece to explore the historic Roman ruins with Axel Boethius — a Roman and Etruscan Archeologist and founder of the Swedish Academy in Rome.

During the academic year 1921–1922, Wasson taught English at Columbia University. He then became an editorial writer and state political correspondent at the New Haven Register.

Three years later, in 1925, Wasson became the associate editor of the monthly “Current Opinion” in The Herald Tribune, writing weekly signed columns in the financial news department.

In 1928, R. Gordon Wasson began working in banking. He joined the Guaranty Trust Company of New York and spent extended periods in London and Argentina. Six years later, the Guaranty Trust merged with J.P. Morgan and Co.

Wasson climbed up the ladder at J.P. Morgan, eventually becoming the Vice President for Public Relations, and worked in this role until his retirement in 1963. During his time at J.P. Morgan, he met his future wife, Valentina Pavlovna Guercken, whom he married in 1926.

Valentina was the catalyst that would change Wasson’s views on fungi and spark his interest in the role of mushrooms in history, religion, and different world cultures.

Wasson’s Introduction to Mushrooms

Robert Gordon Wasson was introduced to mushrooms — although not necessarily psychedelic ones — by his wife, Valentina Pavlovna.

On their honeymoon in the Catskills mountains, Valentina found the same mushrooms she foraged during her early life in Russia. Wasson, who was raised in a typical American family of the time, didn’t understand wild mushrooms and labeled them as poisonous and inedible.

As Wasson wrote in a LIFE Magazine article:

In the afternoon of the first day in the Catskills, we went strolling…. Suddenly my bride spied wild mushrooms in the forest, and racing over the carpet of dried leaves in the woods, she knelt in poses of adoration before first one cluster and then another of these growths. She was overcome with joy at seeing the same kinds of mushrooms in the United States that she had seen in Russia.”

That evening, Valentina added the mushrooms to everything she cooked. Wasson refused to eat the food and was convinced the mushrooms would make him a widower by the morning — not exactly the kind of thing you’d expect to hear from someone who would become one of the most famous authorities on psychedelic mushrooms.

Wasson had grown up believing that fungi picked from nature were dangerous, whereas Valentina had been encouraged to gather mushrooms for the dinner table in her early life in Russia. These conflicting views and contrasting upbringings pushed them into a lifelong search to discover why their viewpoints were so opposite.

Although Wasson remained a banker until retirement, he began to vacation with his wife Valentina to places where the people loved mushrooms. They traveled across Friesland, Lapland, Provence, and Basque Country in search of mushrooms and their cultural uses and significance.

Wasson Becomes an “Ethnomycologist”

Robert Gordon Wasson and his wife would embark on “mushroom hunting” adventures for several years. He created a term for their area of inquiry that would become the new accepted title for the study of mushrooms in people’s cultures. This term is called “ethnomycology.”

The material Wasson and Valentina collected on mushrooms, and culture became voluminous. Wasson decided to publish a study in the form of a book. While preparing the content, he realized just how many references there were to mushrooms in religion.

Robert and Valentina Wasson asked a question that would alter the course of their studies and adventures forever. They wondered whether ancient cultures worshiped mushrooms. After all, this would explain why pictures and texts of mushrooms were so prevalent in religious artifacts.

If mushrooms, or a particular mushroom, was worshiped, which species was it, and why was it considered holy?

This was when Wasson and Valentina’s work took a U-turn. Instead of simply studying the mushroom’s place in cultural history, they started to search for the possible religious significance of mushrooms.

They began by studying the shamanistic use of hallucinogenic mushrooms by the primitive people of Siberia, who still use psychedelic fungi to this day. They found that these mushrooms were highly regarded and respected by the Siberians and several other ancient cultures.

They were looking for a specific type of fungus that had supposedly been consumed in cultures across the globe, from Siberia to China and India to the Americas.

They found references to psychedelic mushrooms in Greek cultures, labeling them “the food of the gods,” and discovered stone carvings representing mushrooms in Guatemalan cultures.

The second turning point of their study had the potential to show them what the mystery “sacred mushroom” is and came in the form of a letter.

Richard Evan Schultes, an ethnobotanist, presented evidence of a “mushroom cult” in Mexico. In the letter, he explained that he had witnessed a shamanic ritual where the participants used some kind of psychedelic mushroom to reach a trance-like state. He also included a specimen of the psychedelic fungi that we now know was Psilocybe mexicana.

This letter led the Wassons to their first expedition in Mexico to the town mentioned by Richard Evan Schultes. They went there to seek out the “magic mushroom cult” that used psychedelic shrooms in their ceremonies…

Wasson’s Travels Throughout Mexico

After receiving the information from Schultes, Robert Gordon Wasson and Valentina Wasson traveled to Huautla de Jiménez to find the Mazatec people who used these mysterious hallucinogenic mushrooms. They were accompanied by Roberto Weitlaner — the person who inspired Schultes to go in search of the psychedelic shroom.

During this first expedition, Wasson became convinced that these psychedelic mushrooms were responsible for seeding religion in primitive humans. Both Robert and his wife Valentina would go on to consume these psychedelic mushrooms, which provided them with their first insight of how exactly they make you feel.

They spent much of their time in Mexico from 1953 to 1954, indulging in the Mazatec culture of mushroom use. Wasson would also go on to collect samples of different psychedelic mushroom species, such as Psilocybe mexicana and Psilocybe cubensis.

Some of these samples would make it into the hands of other pioneers in psychedelics, such as Albert Hofmann — the first person to synthesize LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide). In 1958, Hofmann would take these samples and isolate the compound responsible for the psychedelic effects they produced — and so, psilocybin was discovered.

On February 13, 1957, Wasson published a 15-page article in LIFE Magazine detailing what he and his wife experienced while in the Oaxaca region of Mexico.

The article described the cultural and spiritual use of psychedelic fungi by the Mazatec people. In the article, Wasson labeled these psychedelic mushrooms as “magic mushrooms” — this is where the name that we use to describe several species of psychoactive fungi today comes from.

The article, titled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” described the many events that took place in the small town of Huautla de Jiménez, including his experience consuming magic mushrooms with Maria Sabina. This caught the interest of thousands of people who would go on to visit the curandera.

Robert Gordon Wasson Meets Maria Sabina

Robert Gordon Wasson’s search for magic mushrooms led him to the small village of Huautla de Jiménez in Oaxaca, Mexico. Here, he met the famous curandera Maria Sabina — a healer that used psychedelic mushrooms in her ceremonies.

Before Wasson’s arrival, Maria Sabina wasn’t famous at all. It was when Wasson flew back to America and composed the article on his experiences in LIFE magazine that her name became known.

During his time in Huautla de Jiménez with Maria Sabina, Robert Gordon Wasson took part in one of her traditional mushroom ceremonies. The ceremony involved the consumption of psilocybin-containing mushroom species such as Psilocybe mexicana, Psilocybe caerulescens, and Psilocybe cubensis.

Maria would use these mushrooms alongside tobacco smoke, mezcal (agave-based alcohol), and ointments made from native medicinal plants. She would use Mazatec chants, poetry, and incantations alongside these substances to enter a “shamanic trance.”

While Maria and the participants of the ceremony were under the influence of these substances, she would heal the person in need. She was supposedly successful in healing hundreds of people in these ceremonies, but she never credited herself. Instead, she’d give all the praise to her “sacred mushrooms” as they were the ones that showed her the remedies.

Although Maria’s mushroom ceremonies were all about healing, Robert Gordon Wasson didn’t describe them as such in his 1957 article in LIFE Magazine. Instead, he described the experience as highly spiritual — writing about a divine and euphoric experience where he touched hands with god.

This description of his otherworldly experience urged hundreds of people to seek out Maria Sabina and travel to her small town of Huautla de Jiménez to consume the magic mushrooms.

People from all walks of life began turning up to see Maria Sabina, including several celebrities. Among them were the likes of John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Pete Townsend, and Mick Jagger. It’s even believed that Walt Disney visited Maria Sabina, and his experience with mushrooms influenced his creation of the Disney Universe.

This all sounds fantastic, but unfortunately, it would lead to the demise of Maria Sabina. The villagers shamed her for bringing Westerners to their village and eventually burned her home down and banished her from her lifelong community.

Maria Sabina famously said, “It’s true that Wasson and his friends were the first foreigners who came to our town in search of the Holy Children (the mushrooms) and that they didn’t take them because they suffered from any illness. Their reason was that they came to find God.”

Unfortunately, the twisted view that R. Gordon Wasson portrayed of Maria Sabina and her mushroom ceremonies led to a tragic turn of events for Maria and her family. On the flip side, this chain of events did open up the minds of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people, and it started the psychedelic revolution.

Wasson’s Work With Psychedelics In the 1960s & 1970s

After the experience with Maria Sabina and Wasson’s accidental destruction of her sacred rituals, he was crushed. With shamans appearing across Mexico offering westerners “psychedelic services” regardless of the intent, Wasson felt that these “sacred rituals of enlightenment” had been tainted.

In light of this, Wasson and his wife Valentina continued to search for the roots of psychedelic mushrooms in religion among other cultures. They would perform research in Guatemala, New Guinea, and Borneo in the years following the LIFE Magazine article.

Tragically, Valentina died in 1958. Of course, Wasson was devastated by the loss, but it also drove him to work harder on the research that they had begun together.

In 1963, Robert Gordon Wasson retired from his role at J.P. Morgan and Co. to set off for the Orient with a translator by the name of Wendy Doniger. With his translator, Wasson dissected the oldest religious text ever discovered — the Rigveda.

Wasson was convinced that the “divine plant” mentioned in the text was not a plant but the psychoactive mushroom Amanita Muscaria (Fly Agaric). He went on to prove his theory and trace this mushroom’s influence from Russia through to India, the Middle East, China, and into Eastern Europe.

Once Wasson returned from the Orient, he began focusing on the ancient Greek Rites of Aleusis — a group of yearly rituals held at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece.

Robert Gordon Wasson, alongside Carl Rock and Albert Hofmann, proved that these ancient rituals incorporated the use of ergot — a hallucinogenic fungus used to synthesize LSD. Wasson concluded that it was likely that Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates (the three big Greek philosophers) experienced a mystical state similar to that of LSD.

Wasson continued to travel and lecture about psychedelics and their impact on history, religion, and world cultures. He wrote several pieces on ethnomycology before passing away at the ripe old age of 88.

He passed away while visiting his daughter in New York on December 23, 1986, shortly after finishing a book titled “Persephone’s Quest” — a compilation of his theories on psychedelics in early religion. Robert Gordon Wasson lives on in his writing, and his legacy was passed down to his son and daughter.

R. Gordon Wasson’s Impact on the Psychedelic World

Robert Gordon Wasson is considered a pioneer in the field of psychedelics. If Maria Sabina is “the mother of magic mushrooms,” then R. Gordon Wasson is the father.

He had a huge impact on the world of psychedelics — magic mushrooms and psilocybin in particular. He made magic mushrooms known across the western world and inspired many to go in search of psychedelic fungi.

Wasson introduced the world to magic mushrooms and psilocybin, which lead to further research into the potential uses of psychedelic compounds in therapy and medicine. Without this introduction, the research that followed from the 1950s up until now may not have happened.

His groundbreaking research on the impact magic mushrooms and other naturally-occurring psychedelics had on religion shocked the world and made way for an era of scientific study. Without Wasson and Valentina’s determination to discover how mushrooms fit into history, who knows where we would be now.

Books By Robert Gordon Wasson

Robert Gordon Wasson wrote several scholarly articles and published a handful of books about magic mushrooms and their place in the history of different cultures. His most famous book was The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries, but he published others and was the co-author of many titles in the field.

Several books have been written by other authors about the works of Robert Gordon Wasson as well. Although not written by the man himself, these titles feature many of his studies and research materials.

Here are some of the titles Robert Gordan Wasson wrote, contributed to, or was featured in:

- Mushrooms, Russia and History — Published in 1957

- The Drug Experience: First Person Accounts of Addicts, Writers, Scientists and Others — Published in 1961

- Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality — Published in 1968

- Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens — Published in 1972

- The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries — Published in 1978

- The Wondrous Mushroom — Published in 1980

- Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens and the Origins of Religion — Published in 1992

- The Sacred Mushroom Seeker: Essays for R. Gordon Wasson — Published in 1997

- The Hall Carbine Affair — Published in 2015

Robert Gordon Wasson’s Most Famous Quotes

“In the light of our Mexican discoveries, I was now asking myself whether Soma could have been a mushroom. I said to myself that inevitably the poets would introduce into their hymns innumerable hints for the identification of the celebrated Soma, not of course to help us, millennia later and thousands of miles away, but as their poetic inspiration freely dictated.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“It is in the nature of a hypothesis when once a man has conceived it, that it assimilates everything to itself, as proper nourishment, and from the first moment of your begetting it, it generally grows stronger by everything you see, hear or understand.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“Each of us had harbored a nascent thought that we had been too shy to express even to each other: religion possibly underlay the myco-, phobia contrast that marked the peoples of Europe.“ — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“Ecstasy! In common parlance ecstasy is fun. But ecstasy is not fun. Your very soul is seized and shaken until it tingles. After all, who will choose to feel undiluted awe? The unknowing vulgar abuse the word; we must recapture its full and terrifying sense.” — R. Gordon Wasson

“The Indian (or more precisely Amerindian!) communities that knew the sacred mushrooms continued to treat them with awe and reverence and to believe in their gift of second sight, – rightly so, as the reader will see when he reads our account of our first velada, pp 33-8. Traditionally they have taken the simple precaution not to speak about them openly, in public places, or in miscellaneous company, only with one or two whom they know well, and usually by night. White people seldom know the Indian languages and seldom live in Indian villages. And so, without planning, the Indian by instinct has built his own wall of immunity against rude interference from without.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“Ergot, growing millennia later on certain cultivated grains, seems to have coincided in its arrival on the human stage with the discovery by Man of agriculture.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“Early Man in Ancient Greece could have worked out a potion with the desired effect from the ergot of wheat or barley cultivated on the famous Rarian plain adjacent to Fleusis; or indeed front the ergot of a grass, called Paspalum distinct, that grows around the Mediterranean. If the Greek herbalists had the intelligence and resourcefulness of their mesoamerican counterparts, they would have had no difficulty in preparing an entheogenic potion: so said Albert Hofmann and he explained why.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“Three millennia ago Soma was known to the Brahmans, who composed many hymns exalting it. The hymns to Soma are still being sung, yet no one, not even among the Brahmans, knows what it was.” — R. Gordon Wasson, Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens And The Origins Of Religion

“We were seeking an answer to the strange fact that a mushroom, one single species, the pucka, was ‘animate’ in their language, was ‘endowed with a soul’, like all animals and human beings, but unlike all other vegetation, which is construed grammatically as ‘inanimate’, as ‘without a soul’.” — R. Gordon Wasson

R. Gordon Wasson’s Research Papers

- Wasson, R. G. (1944). Another View of the Historian’s Treatment of Business. Business History Review, 18(3), 62-68.

- Hughes, J. P., & Wasson, R. G. (1947). The etymology of Botargo. The American Journal of Philology, 68(4), 414-418.

- Wasson, R. G. (1956). The divine mushroom: primitive religion and hallucinatory agents. Proc Am Philos Soc, 102, 221-223.

- Wasson, R. G. (1961). The hallucinogenic fungi of Mexico: an inquiry into the origins of the religious idea among primitive peoples. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 19(7), 137-162.

- Wasson, R. G. (1962). A new Mexican psychotropic drug from the mint family. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 20(3), 77-84.

- Wasson, R. G. (1963). The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of Mexico and Psilocybin: A Biography (Second printing, with corrections and addenda). Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 20(2a), 25-73c.

- Heim, R., & Wasson, R. G. (1965). The Mushroom Madness of the Kuma. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 21(1), 1-xx.

- Wasson, R. G. (1970). Soma: Comments inspired by Professor Kuiper’s review. Indo-Iranian Journal, 286-298.

- Wasson, R. G. (1971). The soma of the Rig Veda: what was it? Journal of the American Oriental Society, 169-187.

- Wasson, R. G. (1972). The death of Claudius or mushrooms for murderers. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 23(3), 101-128.

- Wasson, R. G. (1973). The Role of Flowers In Nahuatl Culture: A Suggested Interpretation. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 23(8), 305-324.

- Wasson, R. G., & O’Flaherty, W. D. (1982). The last meal of the Buddha. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 102(4), 591-603.

- Ott, J., & Wasson, R. G. (1983). Carved’disembodied eyes’ of Teotihuacan. Botanical Museum leaflet-Harvard University.