Can Psychedelics Help Heal Trauma?

With the right context, guidance, & integration — psychedelics can be an invaluable tool for healing deep psychological & emotional trauma.

We know that some psychedelic substances have proven effective in different realms — from existential anxiety to treatment-resistant depression.

But where do psychedelics stand in the treatment and recovery of trauma?

In this article, we’ll explore if and how different psychedelics can support the process of recovering from trauma.

We’ll also take a glimpse at the field of psychiatry and psychedelics and what is happening in trauma-specific psychedelic research.

How Can Psychedelics Support Trauma Recovery?

Although there is evidence that the intentional use of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes can reduce complex trauma symptoms [1], there is no straightforward answer to why this is.

The human brain is exceptionally complex, not to mention the intricacies of human consciousness, which are still beyond the scope of neuroscience, psychiatry, and psychology.

There are, however, different psychological, spiritual, and neurological aspects that can help us get a sense of why psychedelics offer such a powerful pathway to healing:

1. Reprocessing Sensory & Somatic Processes

The shifting of mental activity into an altered state can open up avenues for many different ways of processing sensory and somatic experiences (both from the present moment and ingrained in memories from the past). It also allows for shifts in how we relate to ourselves, our experiences, and those around us.

These shifts have the potential to facilitate therapeutic interventions.

The two most common types of modern psychedelic-assisted therapy are psycholytic therapy and psychedelic therapy. They both offer different types of altered states of mind.

A) Psycholytic Therapy

Psycholytic therapy, first coined by Roger Sandison, involves the use of low-dose psychedelics (mostly LSD and psilocybin) paired with therapeutic interventions.

In today’s psychedelia lexicon, we could call this a sort of therapeutic microdose regime.

The term psycholytic means “mind loosening.” The effects of these low doses allow for a loosening of conscious and unconscious defense mechanisms without a full hallucinogenic trip.

The subtle loosening of the mind supports deeper introspection in therapeutic settings. This method has also been used to enhance the therapeutic relationship between the patient and therapist, making the rapport and trust-building process easier [2].

B) Psychedelic therapy

Psychedelic therapy, on the other hand, consists of fewer full-dose sessions aiming to reach a psychedelic peak experience. This term was first introduced by Humphry Osmond, who studied and practiced the administration of full LSD doses, followed by intensive psychotherapy work.

This full psychedelic experience is linked to moments of personal revelations and epiphanies, as well as the potential to access repressed memories. In a safe therapeutic space with proper resources, this unearthing of repressed memories and new insights can be harnessed into integration to support trauma processing and healing.

Altered states of consciousness, whether induced through psychedelic substances or different practices such as deep meditation and sleep and dreaming, appear to enrich creativity, inspiration and provide moments of sudden insight and problem-solving [2].

This access to a new state of mental flexibility is believed to support the re-processing and reframing of negative thoughts, traumatic memories, and detrimental mental patterns.

2. Mystical Experiences

Throughout cultures and traditions, psychedelic substances have been used as a means to access mystical and spiritual realms. Many of these substances provide a feeling of connectedness, an expanded sense of empathy, and dramatic shifts of perspective about the self and the world.

A common experience reported with classic psychedelics like LSD is the sense of universal unity: a lack of separation between “me” and “them.”

This experience of union and connection is what many spiritual practices seek to work toward as a state of enlightenment or spiritual wisdom and a path to reduce suffering.

Researchers and psychedelic advocates like Pahnke and Groff talk about the “psychedelic peak experience” as an intense mystical experience that occurs occasionally, not necessarily in every high-dose experience.

Pahnke stated that a peak psychedelic experience is characterized by feelings similar to those of mystical or spiritual experience regardless of the belief system or religion that the user subscribes to.

Some of these feelings include a sense of unity, a deep euphoric or positive mood, a feeling of revelation or clarity, the transcendence of time and space, and a feeling of sacredness or deep connection [3].

Peak experiences also tend to be followed by a lasting improvement in multiple aspects, including the relationship to self and others, and a more positive general outlook.

Generally, a state of elevated mood and positive outlook is reported once the effects of the substance have subsided. This state is known as the psychedelic afterglow.

Panhke states that this afterglow can also alleviate anxiety, reduce rumination over past events, and enhance the ability and willingness to participate in interpersonal relationships. The afterglow tends to last up to a month, a timeframe in which psychotherapeutic work and trauma integration can be enhanced [4].

3. Formation of New Neural Pathways

Modern neuroimaging and observation methods of brain activity such as fMRIs and EEGs have allowed researchers to observe the brain’s activity and changes while under the effects of different psychedelic substances.

Although this research is still in its infancy and has ways to go, there is substantial evidence that classical psychedelics like ayahuasca, psilocybin, and LSD, have strong antidepressant and anxiolytic properties.

Although the focus of this article is on trauma, depression, and anxiety are frequent comorbidities of unresolved trauma and PTSD. The treatment and management of these conditions are therefore relevant to the realm of trauma recovery.

From a neurobiological standpoint, these substances can help alleviate depression and anxiety through a few different pathways. Here are some of them:

A) Inhibiting Activity in the Amygdala

The amygdala is a structure near the base of the brain responsible for emotional processing and response. Hyperactivity in the amygdala is common in individuals with major depressive disorders and those suffering from PTSD.

Classical psychedelics, much like antidepressants, enhance inhibition of the amygdala, bringing a hyperactive amygdala back to balance [5]. This amygdala inhibition also decreases the response to threat-like stimuli, which can reduce levels of anxiety and distress when faced with triggering memories or situations that can be highly activating for those recovering from trauma.

B) Flexible Thinking and Decreased Connectivity in Default Mode Network

Strong connectivity in the default mode network perpetuates thought patterns of negative rumination and negative self-thought. This hyperconnectivity is linked to depression and anxiety [5].

For those who are dealing with the effects of a traumatic experience, the default mode network rumination pattern can present itself in recurring thoughts of self-blame, shame, fear, and mistrust stemming from the trauma-inducing event or series of events.

C) Increased Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to adapt and modify connections.

Poor or abnormal neuroplasticity is a physiological characteristic of mood disorders, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. This can lead to reduced learning and concentration capacity, as well as a hindered capacity to reframe thought patterns and adapt to new situations.

Chronic stress (commonly present in PTSD patients and those dealing with different degrees of trauma) can contribute to abnormalities in cognitive function, including mechanisms of neuroplasticity [6].

Substances like psilocybin and ketamine have shown the potential to increase neuroplasticity due to their ability to increase levels of glutamate in the brain’s prefrontal cortex and limbic system circuit [7].

This ability can help patients create new pathways that can lead to new earned ways of coping and responding to stressors. Increased neuroplasticity can help patients develop and integrate new self-soothing and resilience techniques that are a key part of recovery.

D) Memory Reconsolidation

Memory reconsolidation is the process of memories being recalled and then stored again. This is used as a means to ensure the information we keep is as reliable as possible.

In a normal state, this helps us carry out daily activities and remember past learnings like a sort of rehearsal or review. But when traumatic memories resurface and reconsolidate, the feelings of threat have the potential of becoming stronger as the memory goes through loops of reconsolidation.

Treatments that have the potential to disrupt memory reconsolidation may have the ability to support PTSD treatment [8], and several psychedelic substances may facilitate memory reconsolidation interventions.

E) Fear Extinction

Fear extinction is the process of progressively reducing stress responses to a specific trigger.

Exposure therapy or systematic desensitization work on this premise to treat different anxiety disorders by slowly exposing a patient to different degrees of the triggering situation while guaranteeing safety. This can slowly reduce the activation of emotional stress responses by the nervous system.

Because of the reduced fear response that some psychedelics have shown to have as an effect, exposure in a safe and controlled manner can support processes of coping with triggering experiences.

Many psychedelic substances have been shown to support fear extinction processes. If done in a regulated and safe way to reduce the risk of re-traumatizing or triggering the patient, these methods may have the potential to help trauma patients regain the ability to respond in a healthier manner to intrusive memories or triggering situations that may interfere with day-to-day life.

Which Psychedelics Can Help With Trauma Recovery?

Research on the use of psychedelics in the psychotherapeutic context is fairly new and has seen a fair amount of obstacles since its boom in the 60s.

Although many of these substances have been used for centuries and even millennia, modern scientific research and standardization of their safe use still have ways to go, and certain substances have far more substantial research than others.

Here is a brief review of some of the most commonly used and observed psychedelics in the realm of trauma processing and recovery.

A) LSD For Healing Trauma

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) was one of the most researched and explored substances in the 40s-60s.

Since the synthesis of LSD in 1938, thanks to the work of Albert Hoffman, its use for psychotherapy has been studied and experimented with by some of the biggest names in the psychedelic space.

LSD has made itself a name for the ability to retrieve repressed memories. In traditional psychoanalysis, accessing the entirety of the traumatic memories was believed to be a key part of the recovery process. Therapists like Groff considered it a tool to confront past traumatic experiences and believed that combined with therapy, it could help retrieve and organize painful memories to create an accurate, organized, and detailed picture of the events [9].

This approach has since been abandoned by many contemporary therapists, given the high risk of re-traumatizing and further hurting a patient’s psyche. While accessing memories can help understand and integrate painful experiences, the repression of overwhelming memories is the psyche’s defense mechanism to keep us safe, therefore accessing these memories does not come free of risk.

It is imperative then that those who have a history of trauma (known or unknown) and choose to use LSD as a means of recovery do so within a safe container where resources and support are available in order to bear and process the experience. This is why LSD-assisted psychotherapy is normally done as an immersive session with the necessary preparations and follow-up therapeutic integration.

In addition to its potential to retrieve repressed memories, LSD is also known to be a catalyst of spiritual or mystical experiences. Users frequently report a feeling of unity and universal interconnectedness. As we explored earlier in the article, the mystical experience can be a catalyst for healing, and the peak experience and its following afterglow can enhance the therapeutic process.

Neurologically, LSD has been shown to reduce strong emotional activation in the amygdala when people are faced with a fear-inducing stimulus [10]. This mitigation of fear response can create a stronger frame in order to face emotionally challenging memories such as those tainted by trauma.

Though research on LSD-assisted therapy has just recently rekindled in the last decade, current clinical trials are being conducted by organizations like MAPS, which has now successfully completed their phase 2 pilot study showing positive results in anxiety management in subjects after only 2 sessions of LSD assisted psychotherapy.

As with most of these substances, more research is needed before these treatments make it safely into the mainstream of psychotherapeutic work, but more trials are underway, and the field is moving faster than it has since the ban in the 60s.

B) MDMA For Healing Trauma

MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is prised in the therapeutic field due to its ability to reduce fear response in triggering situations and support introspection [11]. Because of this, the potential use of MDMA in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has piqued the interest of the psychiatry realm.

The first line of treatment for PTSD is psychotherapy, which has proven to be more effective than a pharmacological approach relying on SSRIs [12]. However, full recovery is challenging and often not achieved.

Different types of trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and exposure therapies, have shown in clinical studies a recovery rate of 67% for those who have completed a full treatment round. Conversely, the recovery rate was only 54% for those who only partially completed it [13]. This leaves a large population, at least 33% of patients, without any improvement of symptoms throughout the therapeutic processes.

In MAPS’ first clinical trial with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, patients with PTSD showed promising results. After a series of clinical administrations paired with psychotherapy sessions, 83% of participants in the MDMA group showed clinically significant improvement while only 25% percent in the placebo group did [14].

While both of these groups still received high-quality therapeutic support, the group that was receiving the MDMA dose had a significantly higher rate of reduction of symptoms. This data alone should warrant further studies in the use of MDMA for trauma healing.

MAPS has now finished a successful phase 3 trial, which was a stepping stone for the FDA’s eventual approval of MDMA-assisted therapy to be administered to patients with PTSD.

MDMA also seems to have effects on emotional processing brain mechanisms. In fMRI images, the effects of MDMA in the brain appear to be most active in the amygdala and hippocampus, two of the areas that are heavily involved with emotional processes and memory.

This suggests that it has the potential to alter the way memories are perceived. In fact, study participants reported perceiving bad memories as less negative and good memories as more euphoric, vivid, and intensified while on MDMA [15]. This could be a great tool in trauma processing and the reframing of traumatic memories.

MDMA has also been shown to increase the activity in the frontal cortex, which is often impaired in patients with complex trauma or PTSD [16].

C) Psilocybin For Healing Trauma

Psilocybin, the active compound in magic mushrooms, has also been successfully used to reduce anxiety and alleviate depression.

Although research in psilocybin efficiency in trauma recovery is still in its infancy, previous studies have shown increased neurogenesis and synaptogenesis with the therapeutic use of magic mushrooms. This can lead to quick antidepressant effects due to the facilitated neuroplasticity [7].

Like LSD and MDMA, psilocybin seems to decrease activity in the amygdala. Since people with PTSD often have increased activity in the amygdala, this effect may support nervous and emotional regulation and aid the process of trauma integration [17].

D) Ketamine For Healing Trauma

Although not really a psychedelic drug, the use of ketamine has fallen under the umbrella of psychedelic therapy due to its similar effects on the brain, especially its strong effects on neuroplasticity.

The study for ketamine use in psychiatric settings has been ongoing since the early 2000s, and in March 2019, ketamine was approved by the FDA to be used to combat treatment-resistant depression.

Ketamine is extremely fast-acting, and patients see results after only one dose. It quickly crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts through several signal pathways. It mostly binds to glutamate receptors which are involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity, as well as memory and new learning. As we’ve seen before with LSD and psilocybin, this enhanced synaptic plasticity can support therapeutic processes and help the re-processing of emotionally challenging experiences.

Research on ketamine for trauma-specific purposes is fairly new. In 2014 studies similar to those assessing the use of ketamine for depression showed that ketamine could also have a positive effect on patients with diagnosed PTSD showing significant relief of symptoms for up to two weeks [18].

Ketamine may also be used to target traumatic memories directly. The effects that ketamine has in glutamate signaling can interfere with the accessing and processing of memories. Some studies have observed ketamine can block memory reconsolidation [11,19].

Although ketamine has shown promising short-term results in clinical use for treatment-resistant depression, research on this substance as an aid for trauma recovery is in its infancy and so far mostly observed in animal testing.

It is important to note that the therapeutic use of ketamine mostly relies on the rapidly enhanced synaptic plasticity that allows for the rewiring of neural pathways; however, the window of this intense receptiveness to new neural pathways and connections is small (a week or two), and the positive effects of the treatment may wear off almost entirely if intervention and proper therapeutic support are not promptly administered.

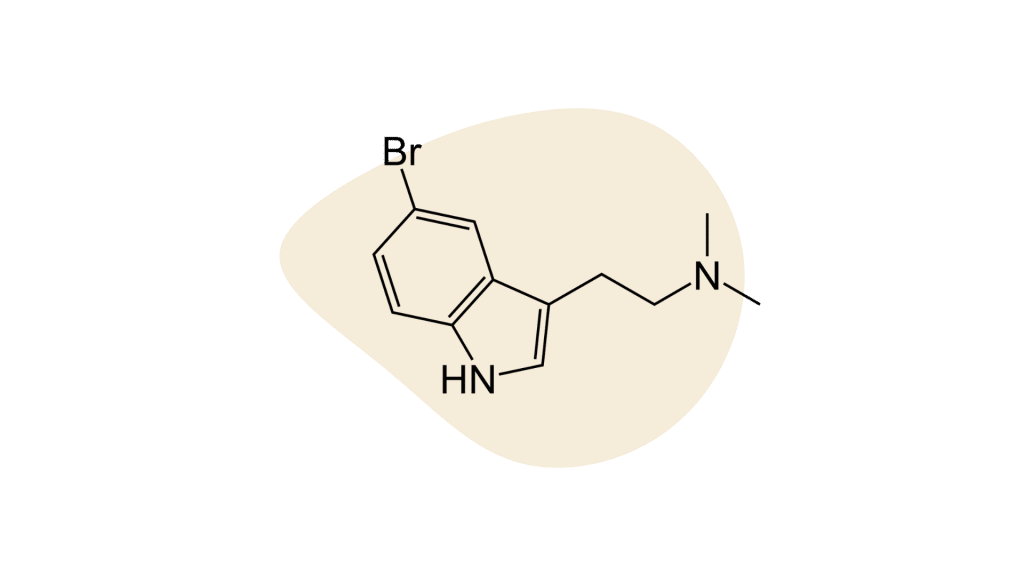

E) DMT For Healing Trauma

DMT (dimethyltryptamine) has been used for centuries in South American indigenous communities as a path of healing and knowledge seeing. It plays a significant role in the spiritual practices of many of these groups.

Experiences with DMT in different settings are known for their intense effects not only during the ceremony itself but spanning out for an afterglow that can last roughly a month.

Though DMT, like other classic psychedelics, is known to have antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, research in this area is very limited.

Ayahuasca and bufo toad venom (5-MeO-DMT) are two forms of DMT preparation that have piqued the interest of psychiatrists, neurologists, and mental health professionals.

DMT, just like psilocybin and LSD, is a serotonin receptor agonist and has shown to have quick antidepressant and mood-enhancing effects. Several studies have observed a significant reduction of subjective depression scales after participation in ayahuasca or Bufo toad ceremonies [20,21,22].

Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a plant brew traditional of Amazonian indigenous groups and used in rituals and ceremonies normally under the guidance of a shaman. Although ayahuasca ceremonies have gained more and more popularity and have brought a large influx of tourism to the Amazon rainforest, clinical studies on its safety and efficacy are limited, partly due to international laws that restrict its use.

In terms of therapeutic use for trauma recovery, ayahuasca is hypothesized to affect memory reconsolidation and enhance fear extinction leading to a decreased intensity of traumatic memories during memory updating [23].

5-meO-DMT (Bufo Toad Venom)

Another common practice in spiritual and healing settings is the inhalation of 5-meO-DMT.

Local to southwestern states, including Arizona, Colorado, and California, as well as northern Mexico, the Bufo alvarius toad secretes a toxic venom that has been harvested and used for centuries for its strong hallucinogenic effects.

It has been suggested that on top of its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, a single dose of 5-meO-DMT can significantly strengthen mindfulness skills [23]. This could support trauma recovery through mindfulness-based, cognitive-behavioral approaches that help the patient decenter from the traumatic experience and observe it as an experience from the past while not identifying with it or physiologically reliving the experience when triggered.

Like ayahuasca, 5-meO-DMT is a schedule 1 substance across North America, and clinical research on its effects is limited, but it has promising potential for further research of its therapeutic properties.

A Brief History of Psychedelics in Healing Spaces

Although psychedelic therapy is increasingly popular in mainstream culture today, mind-altering substances are not new to healing spaces. The use of plant medicines to access altered states of consciousness dates back millennia and has been a part of cultural practices since time immemorial.

The Vedas, a set of ancient Hindu texts dating back to 1500-800 BCE, mention “Soma”, a hallucinogenic drink used in Vedic spiritual rituals. Researchers have debated the exact nature of the drink, first speculating it could be made from the Amanita muscaria mushroom.

Centuries later, Terence Mckenna would suggest that this ancient mystical drink was more likely to be made from Psilocybe cubensis mushroom, aka magic mushrooms.

Ancient Greeks offered young men a wheat drink in rites of initiation that is believed to have been inoculated with Ergot fungus, a compound that closely resembles LSD.

The Americas certainly didn’t stay behind. The ceremonial use of cacti native to central America like mescaline has archeological evidence that dates back around 5000 years, and native communities around the Amazon rainforest are known for their Ayahuasca ceremonies, a practice that has evidence to date back at least 1000 years.

Needless to say, the use of psychedelics far preceded their use in post-colonial western cultures, but throughout the last centuries, they have permeated into all cultures, and the use of psychedelics is widespread worldwide now.

Counterculture Movement & Changing Paradigms

The ’60s marked the boom of psychedelia. The hippie counterculture was heavily influenced by not only the use of psychedelic substances but also by reminisces of ancient cultures that used them as part of their spiritual practices.

During this time of shifting paradigms, psychiatric research was flourishing with promising observations about the efficacy of psychedelics to treat psychiatric concerns.

Between 1950 and 1967, psychedelic research was rampant, and big names like Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (Ram Dass), and Stanislav Grof were leading the conversation on the use of psychedelics (mainly LSD) as a powerful tool to assist psychotherapy.

USA Bans Psychedelics & Psychedelic Research

Amidst the civil rights movement, anti-war protests, sexual liberation activism, and general counterculture rebellion, the U.S government pushed back on the use of recreational drugs (especially marijuana and LSD) under the argument that they perpetuate disobedience, violence, and harm.

MK Ultra was a decades-long experiment using LSD as a possible intelligence weapon to alter the minds of their targets. This project only led to an even more sour taste after it was discovered the feds were dosing unsuspecting citizens seemingly willy-nilly. In 1967 the U.S government banned the use of LSD and recalled all previous government grants to study its psychiatric benefits.

Countries around the world followed the steps of the U.S., and LSD (as well as many other psychedelics) became a schedule 1 substance despite little evidence of risk involved.

Research came to a screeching halt with the criminalization of psychedelic drugs.

Current Efforts in Psychedelic Therapy For Healing Trauma

The past decade has been a sort of rebirth of psychedelic research since the start of the war on drugs in the late 60s.

Substance decriminalization and the reopening of legal avenues for psychedelic research have allowed space to rekindle the halted research.

Organizations like MAPS, Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, and Stanford Psychedelic Group, to name a few, have dived back into research with the promise of improved psychiatric treatments.

Renowned names in the health and psychotherapy fields like Gabor Mate, Bessel van der Kolk, and Peter Levine, among many others, are proponents of psychedelic use within a therapeutic context and recognized educational institutions like Naropa University, CIIS, Fluence, and MAPS now offer programs in psychedelic-assisted therapy and psychedelic integration counseling.

Current Legal Status of Psychedelics in the US

What’s Next for Psychedelics & Trauma?

As stated before, research in psychedelic therapy is generally limited and still has a way to go. While many studies and efforts have shown strong evidence to support the use of psychedelics to treat anxiety and depression, not a lot of research has gone into trauma-specific uses of these substances.

As of now, MDMA is the only substance that has been approved by the FDA as a breakthrough therapy for PTSD, but other substances, while still used in therapeutic spaces around the world with promising reported effects, are still behind on research specific to their efficacy and safety in trauma healing.

The use of psychedelics as a way of self-discovery and healing is still rampant in the shadows, and people around the world, including mental health professionals, are still advocating for their use, getting trained in modalities like psychedelic integration and psychedelic-assisted therapy, and even facilitating guided experiences as part of their practices.

The field definitely warrants more research, and organizations like Compass Pathways, MAPS, and others around the world are beginning to tap into the potential that other psychedelic substances may have in trauma recovery.

The interest in this field is booming, to say the least, and new research and efforts are starting to respond.

References

- Healy, C. J., Lee, K. A., & D’Andrea, W. (2021). Using psychedelics with therapeutic intent is associated with lower shame and complex trauma symptoms in adults with histories of child maltreatment. Chronic Stress, 5, 24705470211029881.

- Ludwig, A. M. (1966). Altered States of Consciousness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 15(3), 225.

- Pahnke, W. N. (1969). The psychedelic mystical experience in the human encounter with death. Harvard Theological Review, 62(1), 1-21.

- Majić, T., Schmidt, T. T., & Gallinat, J. (2015). Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: when and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences?. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 241-253.

- Muttoni, S., Ardissino, M., & John, C. (2019). Classical psychedelics for the treatment of depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders.

- Pittenger, C., & Duman, R. S. (2008). Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 88-109.

- Ly, C., Greb, A. C., Cameron, L. P., Wong, J. M., Barragan, E. V., Wilson, P. C., … & Olson, D. E. (2018). Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell reports, 23(11), 3170-3182.

- Alberini, C. M., & LeDoux, J. E. (2013). Memory reconsolidation. Current Biology, 23(17), R746-R750.

- Jacobs, A. (2008). Acid redux: revisiting LSD use in therapy. Contemporary Justice Review, 11(4), 427-439.

- Mueller, F., Lenz, C., Dolder, P. C., Harder, S., Schmid, Y., Lang, U. E., … & Borgwardt, S. (2017). Acute effects of LSD on amygdala activity during processing of fearful stimuli in healthy subjects. Translational psychiatry, 7(4), e1084-e1084.

- Krediet, E., Bostoen, T., Breeksema, J., van Schagen, A., Passie, T., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Reviewing the potential of psychedelics for the treatment of PTSD. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(6), 385-400.

- Merz, J., Schwarzer, G., & Gerger, H. (2019). Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological, Psychotherapeutic, and Combination Treatments in Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(9), 904–913.

- Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Westen, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214-227.

- Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. (2011). The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 25(4), 439–452.

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Wall, M. B., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Ferguson, B., De Meer, I., … & Nutt, D. J. (2014). The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD-fMRI responses to favorite and worst autobiographical memories. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(4), 527-540.

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Murphy, K., Leech, R., Erritzoe, D., Wall, M. B., Ferguson, B., … & Nutt, D. J. (2015). The effects of acutely administered 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on spontaneous brain function in healthy volunteers measured with arterial spin labeling and blood oxygen level-dependent resting-state functional connectivity. Biological psychiatry, 78(8), 554-562.

- Francati, V., Vermetten, E., & Bremner, J. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging studies inpost-traumatic stress disorder: review of current methods and findings. Depression and Anxiety, 24(3), 202–218.

- Feder A, Parides MK, Murrough JW, Perez AM, Morgan JE, Saxena S et al (2014) Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat 71(6):681–688.

- Veen, C., Jacobs, G., Philippens, I., & Vermetten, E. (2018). Subanesthetic dose ketamine inpost-traumatic stress disorder: a role for reconsolidation during trauma-focused psychotherapy?. In Behavioral Neurobiology of PTSD (pp. 137-162). Springer, Cham.

- Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Osório, F. L., Sanches, R., Dos Santos, R. G., Tófoli, L. F., de Oliveira Silveira, G., Yonamine, M., Riba, J., Santos, F. R., Silva-Junior, A. A., Alchieri, J. C., Galvão-Coelho, N. L., Lobão-Soares, B., Hallak, J., … Araújo, D. B. (2019). Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological medicine, 49(4), 655–663.

- Sanches, R. F., de Lima Osório, F., Dos Santos, R. G., Macedo, L. R., Maia-de-Oliveira, J. P., Wichert-Ana, L., de Araujo, D. B., Riba, J., Crippa, J. A., & Hallak, J. E. (2016). Antidepressant Effects of a Single Dose of Ayahuasca in Patients With Recurrent Depression: A SPECT Study. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 36(1), 77–81.

- Uthaug, M. V., Lancelotta, R., van Oorsouw, K., Kuypers, K., Mason, N., Rak, J., Šuláková, A., Jurok, R., Maryška, M., Kuchař, M., Páleníček, T., Riba, J., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2019). A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness-related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology, 236(9), 2653–2666.

- Inserra A. (2018). Hypothesis: The Psychedelic Ayahuasca Heals Traumatic Memories via a Sigma 1 Receptor-Mediated Epigenetic-Mnemonic Process. Frontiers in pharmacology, 9, 330.

- Nutt, D. (2019). Psychedelic drugs—a new era in psychiatry?. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 21(2), 139.

- Vollenweider, F. X., & Kometer, M. (2010). The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(9), 642–651.