The Story of LSD, Its Inventor, & Fun but Now Questionable History

LSD has a long history of controversy in America — even the long-celebrated story of Hofmann’s first discovery of its potential is now in question.

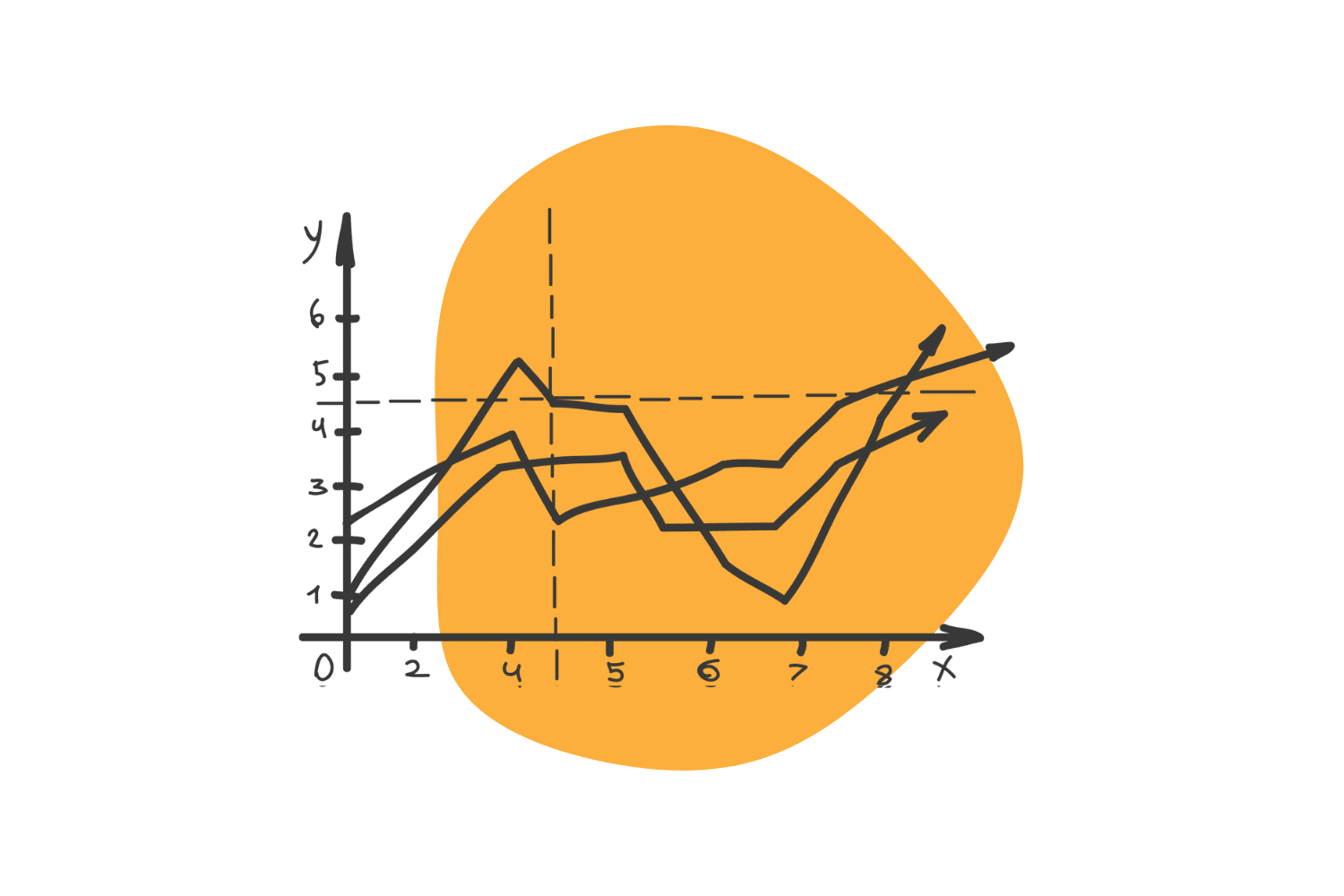

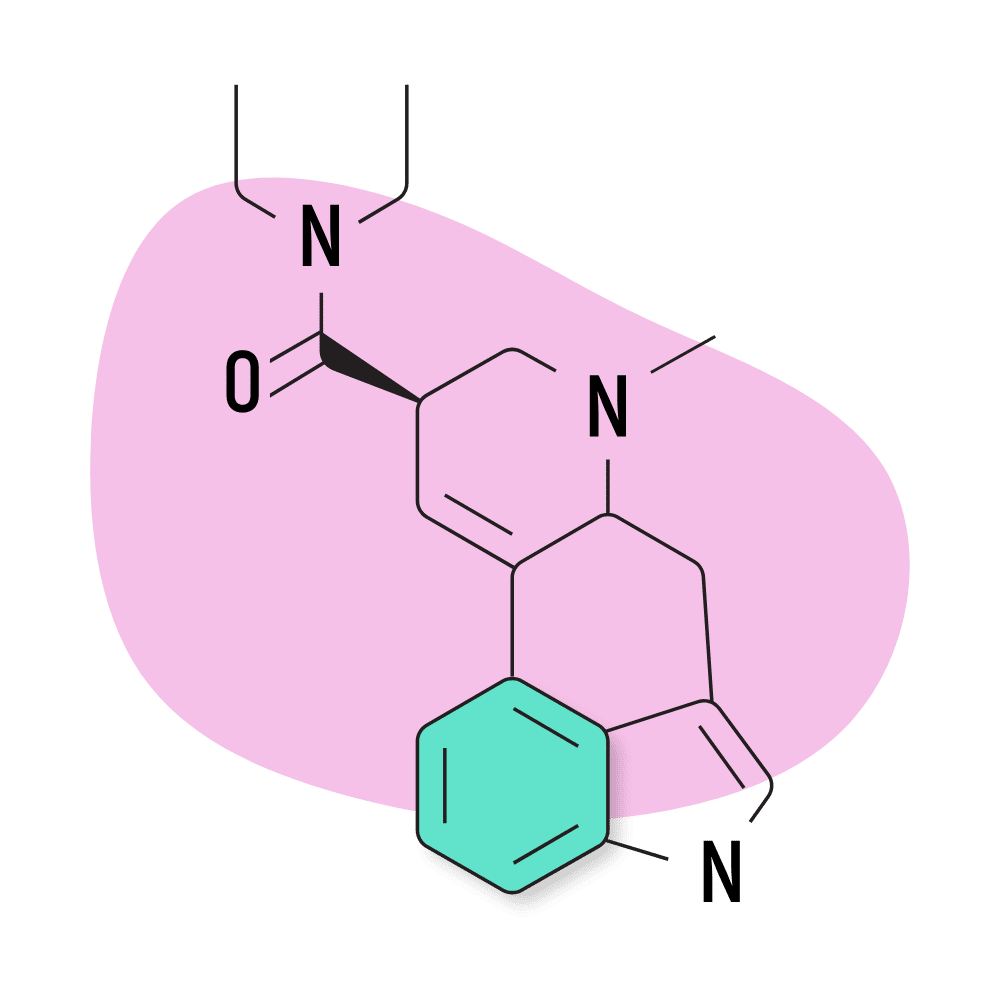

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) is one of the most beloved psychedelics available — not to mention one of the most potent. An active threshold dose of LSD is just 80–100 μg (or 0.08 – 0.1 mg), and the effects can last for 12 or more hours.

Since psychedelics often make people reflect on the past, it’s no wonder many are interested in how this powerful psychedelic came to exist.

The story surrounding its invention has recently come into some controversy, but we’ll take you through the different possibilities out there and talk about the man who pulled it all off.

Who Invented LSD?

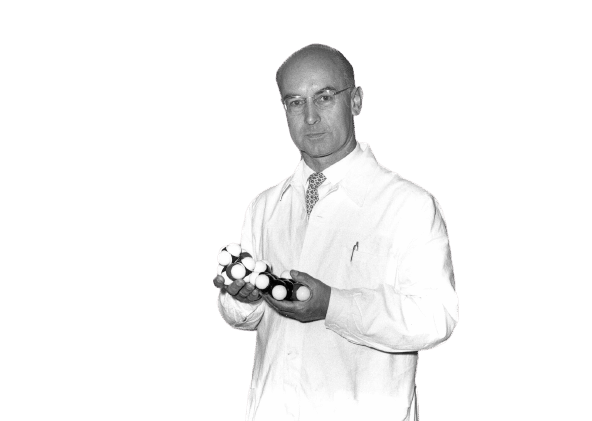

Albert Hofmann was the man who invented LSD.

He first synthesized it in 1938 while working for Sandoz Laboratories on a project identifying the active alkaloids within ergot fungus (Claviceps spp.). The 25th chemical he would synthesize in the lysergamide family was LSD-25, the psychedelic many know and love.

Initial tests didn’t seem to show much (if any) activity in the drug, so Hofmann moved on from it. Until — as the story goes — he revisited the synthesis five years later, telling a group in 1996 that “it was no more than a hunch!”

Who Was Albert Hofmann Before LSD?

Hofmann was a Swiss chemist born on January 11, 1906. He received a degree in Chemistry from the University of Zurich, taking an interest in psychoactive substances and biological structures of animals and plants.

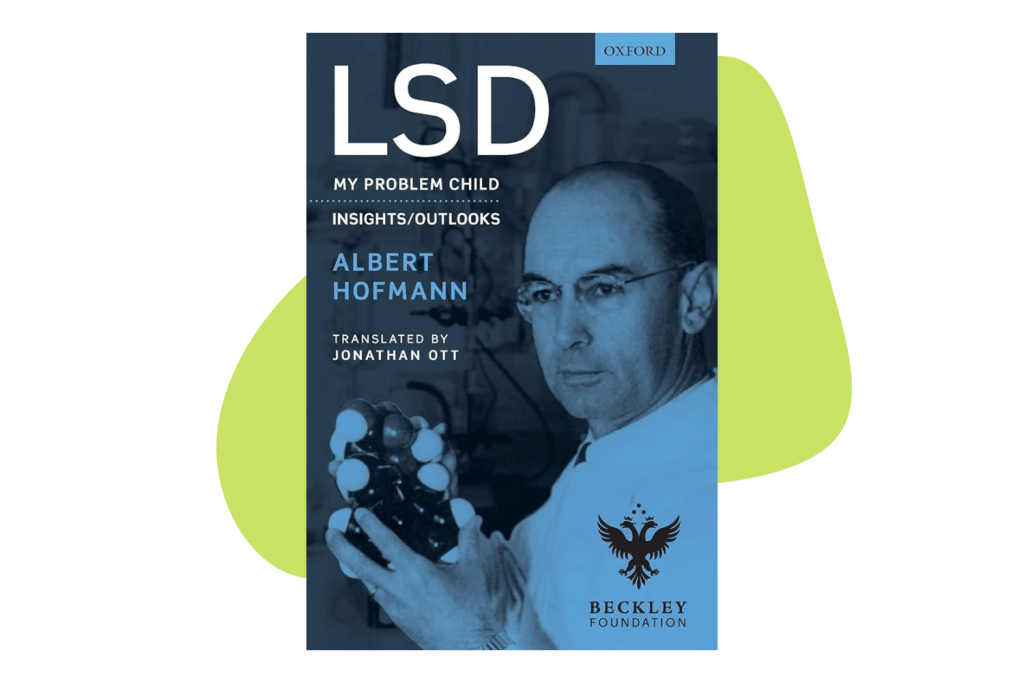

In his book LSD: My Problem Child, Hofmann states he was able to make “use of the gastrointestinal juice of the vineyard snail” to degrade chitin — “the structural material … [of] shells, wings, and claws,” among other things.

This accomplishment was enough to land him his job at Sandoz, where he first began working with Drimia maritima (“Sea Squill”), native to the Mediterranean. His work centered on determining the chemical structure of an alkaloid from the plant, which, after the shuttering of his research, he requested to apply to ergot.

Hofmann was fascinated by ergot and wrote extensively on the history of it in 1978 [2]. He reports several reasons for researching this particular alkaloid, stating it was “a remedy used by midwives for quickening childbirth.”

According to his paper, the discovery of a particular alkaloid — ergonovine — with toxic principles “simultaneously in four separate laboratories” fueled the research.

His interest was two-fold interest in the fungus:

- To determine how best to isolate and synthesize the expensive, hard-to-obtain ergot alkaloids.

- The creation of new ergot-derived alkaloids “from which other types of interesting pharmacological properties could be expected based on their chemical structure. [1]

Through this, Hofmann created several ergot derivatives — including his 25th chemical, Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD-25). In the five years between first creating LSD and discovering its properties, he also produced three medications, including:

- Methergine — Prevents post-partum bleeding

- Hydergine — For “circulation and cerebral function” in elderly patients

- Dihydroergotamine — A “circulation- and blood-pressure-stabilizing” medication

Controversy Surrounding Hofmann’s Invention of LSD

The situation surrounding how Hofmann first came to understand the power of LSD has come under some scrutiny recently. We cover the prevailing story in more detail in our article on Albert Hofmann, but briefly, the story goes:

Hofmann discovered LSD in 1938 while researching different alkaloids of ergot fungus. Initially, he didn’t believe it had any activity, so he set it aside for five years only to accidentally absorb some of it through his skin and intentionally ingest a rather large dosage (250 μg) before taking the most famous bicycle ride in history, now referred to as Bicycle Day.

Recent efforts to look into this have thrown some questions into the validity of the story. Some suggest the story was a fabrication to promote LSD as a tool to combat the effects of WWII.

A post by High and Mighty breaks this theory down further, but here’s a rundown based on a couple of obscure sources and interesting leads:

- Hofmann knew the effects of LSD after he first discovered it but believed it was too powerful to release to the public

- After WWII, “when Europe was in really bad shape,” according to CIA-linked Dr. Willis Harman, Hofmann decided the positives outweighed the potential negatives.

- The “bicycle day” story (which may or may not have a historical basis at all) served the purpose of making LSD seem like a beautiful drug with few side effects

As Rado states: “This could be entirely irrelevant, or it could be pretty important — exactly which will vary from reader to reader.”

What Did Albert Hofmann Do After Inventing LSD?

Hofmann would go on to patent several findings after discovering LSD’s activity in humans in 1943. Some of these included methods of synthesizing, storing, or otherwise manipulating alkaloids — but his most notable other contributions were isolating psilocin and psilocybin.

Hofmann and his team would be responsible for isolating, naming, and synthesizing both of these compounds, which contribute to the effects of magic mushrooms.

He also became an integral part of psychedelic culture — albeit a role he didn’t necessarily always want. His newest edition of LSD: My Problem Child has a forward by Stanislav Grof and details meetings with Ernst Junger, Aldous Huxley, Walter Vogt, and other “various visitors.”

This includes a somewhat contentious interaction with Timothy Leary and a cordial meeting later in life.

How Did Albert Hofmann Feel About LSD?

Hofmann spoke extensively on his role in creating LSD and how he felt regarding the consequences of doing so. He felt LSD was a miraculous discovery with tremendous potential but had regrets about it leaving the research labs.

At nearly 100 years old, just before his death, Hofmann spoke with the New York Times and had this to say:

I was completely astonished by the beauty of nature … It’s very, very dangerous to lose contact with living nature. In the big cities, there are people who have never seen living nature, all things are products of humans. The bigger the town, the less they see and understand nature.

His point, which aligns with that of his book, was regret in the rapid expansion of LSD use leading to a diminishing of how seriously people were taking it. He felt this ultimately killed the drug’s momentum in its earlier years.

Hofmann was irritated by the prohibitive measures taken against LSD and considered the party culture surrounding it to be largely responsible for this.

References

- LSD My Problem Child (4th Edition): Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism and Science: Hofmann PhD, Albert: 9780979862229: Amazon.com: Books. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2023,

- Hofmann, A. (1978). Historical view on ergot alkaloids. Pharmacology, 16 Suppl 1, 1–11.