The Dos & Don’t of Taking Liquid LSD

“Acid allows you to walk through the door to an alternate reality, but most people have no idea how to walk back through.” — Alexander Shulgin

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is typically consumed by placing a small piece of blotter paper soaked in a liquid solution of LSD under the tongue before swallowing it. A newer form of LSD gel tabs is also becoming more popular because they offer all the same benefits of blotters but are stronger and more shelf-stable.

Blotters or gels are the safest (and most convenient) methods of consuming LSD, but some prefer to use diluted liquid LSD droppers instead.

This guide covers everything you need to know about liquid LSD.

What is Liquid LSD?

Liquid LSD can sometimes refer to these two forms:

Pure LSD Crystals Dissolved in a Solvent

When LSD is first synthesized, it’s a white, odorless crystal. It is then ground into a fine powder before it’s dissolved in a solvent (usually ethanol alcohol or distilled water). This dilution is then painted onto blotter art and allowed to dry. The solvent evaporates, leaving behind a thin film of powdered LSD on the surface and inside the pores of the blotter paper.

This process helps standardize the dose and makes it easier to consume.

Some manufacturers will simply sell tincture bottles of LSD dilution instead. This is what most people mean when they say “liquid LSD.” It’s normally used by placing a drop or two of the liquid in water or juice.

Note that the concentration of liquid LSD can vary substantially depending on how diluted it is. This is the reason why most people prefer to use blotter paper instead. One drop of liquid LSD could contain significantly more active LSD than a single blotter square.

LSD Blotter Paper Diffused into a Solvent

“Liquid LSD” may refer to a liquid (usually a bottle of water or alcohol) that has one or more blotters of LSD infused in it — sort of like making tea, but without the heat.

This practice is also called “volumetric doses” and is one of the best ways to make LSD microdoses or to split acid tablets evenly between a group of people.

For example, imagine you had only five acid tabs to share among six people. Rather than cutting a section off each tab, the best method is to drop all of them into a bottle of water, allow it to infuse the water, and then portion out six equal amounts.

What’s The Dose Of Liquid LSD?

Because of the lack of standardization of black-market drugs, it can be hard to tell the concentration of the liquid LSD solutions — a single drop can range from 50 to 500 ugs.

A standard psychedelic dose of LSD can be felt with as little as 100 ugs (depending on the user’s weight and metabolism).

When buying a liquid LSD, look for a label that indicates the potency of each drop or specifies the ratio of crystalline LSD to the solvent.

Here’s a helpful calculator for finding the distal dosage of LSD for specific use types depending on the user’s weight.

Double-check the potency of the DXM you’re using, and look for the addition of other compounds such as acetaminophen which can cause severe liver-toxic side-effects at this dose.

How “Pure” is Liquid Acid (LSD)?

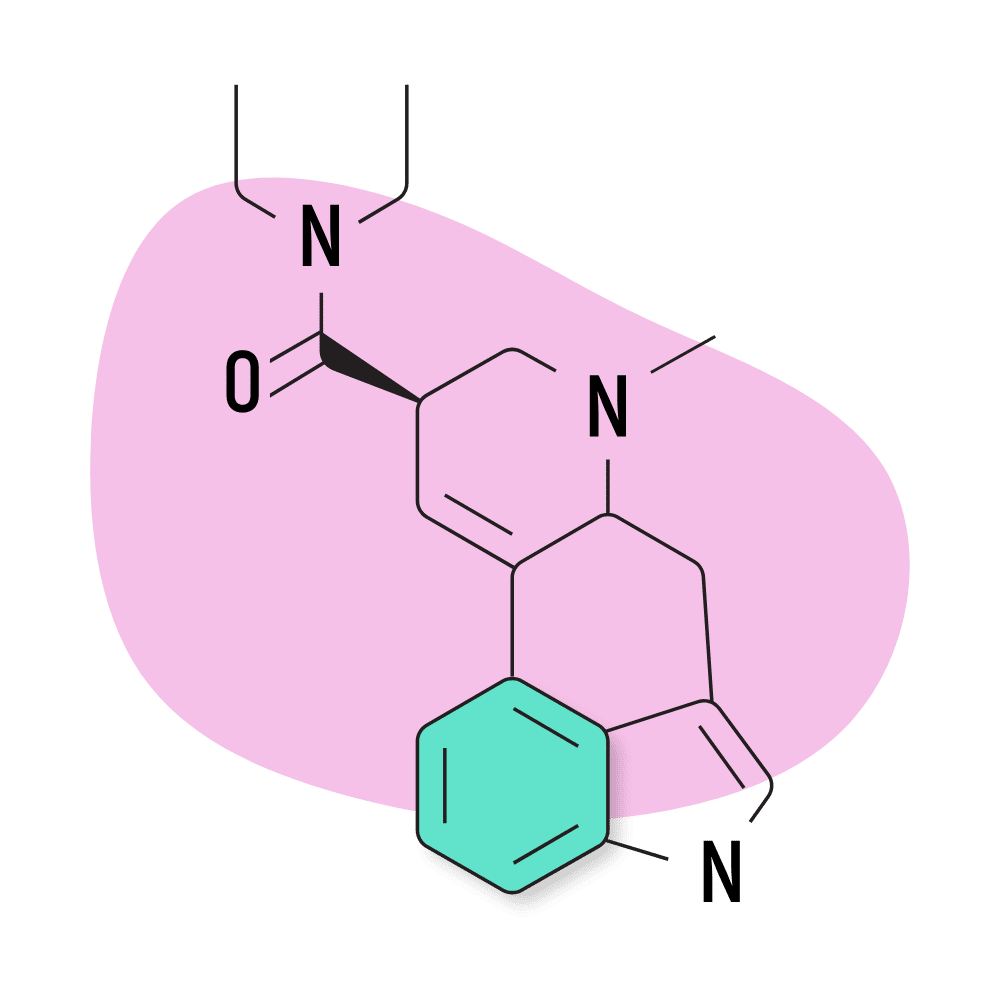

Lysergic acid diethylamide is synthesized from the ergot fungus into colorless, odorless, and tasteless crystals, which are then dissolved in alcohol or distilled water.

When Sandoz Laboratories marketed the drug under the name “Delysid” for use in psychiatry and psychotherapy, it was available as oral sugar-coated tablets that were easy to swallow.

However, Delysid was also available for clinicians in liquid form that could be taken orally by dropping the solution onto a sugar cube or mixing it into a beverage.

These forms of LSD were pharmaceutical-grade and intended for use in medical and scientific settings — not marketed for recreational use.

Today, LSD is a controlled substance only available for research under strict regulation. Using LSD in any form outside of a medical or scientific setting is illegal in many countries. Because of this, there is no standardization for the quality or purity of LSD products, including liquid LSD, on the black market.

The lack of standardization for illegal drugs can lead to significant safety risks for individuals who consume them.

Most of the time, it means that the potency and purity of LSD can vary greatly from one batch to the next, and there’s no way to guarantee that what’s sold as LSD is actually the drug it claims to be, which is why it’s essential to test your drugs.

How To Use Liquid LSD

Some people who regularly use LSD prefer the liquid form over blotters or gels.

This is because it can keep for many years (in an alcohol-based solution) when properly stored. The other reason is that it offers more versatility for different dosing situations (microdosing to a full psychedelic trip).

And if you manage to get ahold of a good source of liquid LSD, it winds up being more cost-effective overall than purchasing blotter tabs.

Most liquid LSD comes in a dropper bottle that administers about 0.05 mL of liquid per drop. Please note that this is not the rule, and every batch likely contains a different concentration of LSD.

You can calculate your dose based on the concentration of the LSD in the solution divided again by the drop.

Here are some methods people use to take liquid LSD:

Drop Some LSD Onto a Sugar Cube

This classic practice involved placing just one or two (depending on potency) drops of LSD liquid onto a sugar cube and holding it in your mouth until it fully dissolves.

Place a Drop of LSD Directly Under the Tongue

After placing the drop, hold it there to allow its absorption into the bloodstream through the microcapillaries.

We only recommend this if you’ve got steady hands. Dropping the solution right into the mouth adds the risk you accidentally administering too much. Just one drop too much can result in an entirely different experience.

Dilute With Some Water or Juice

A safer method of using liquid LSD is to dilute it in some other liquid first. This practice reduces your chances of taking too much because you can first add the drop(s) and then consume either the whole cup or leave some behind to control the dose.

LSD has no taste, so you won’t need to worry about masking it like other psychoactive substances. Be cautious about dropping your LSD into anything warmer than room temperature. So this leaves things like tea and coffee out of the equation.

DIY Blotter Papers Using Liquid LSD

We don’t suggest making blotters unless you’re a chemist or know what you’re doing. You can easily ruin large batches of LSD this way if you’re not careful.

Additionally, making LSD blotters efficiently requires large amounts of liquid LSD — more than most people can afford or have access to. Most people are better off sourcing tabs than making them at home.

The biggest issue with transferring liquid LSD to blotter paper — “laying tabs” — is that you can end up with inconsistent tabs if you’re using a syringe or a dropper applicator and dabbing your doses onto each square.

That means one dose might blow your mind, while the other nine won’t do anything at all. Consistency when making blotters is very important — in many ways, it’s the whole point of the operation.

If the LSD isn’t precisely laid in this manufacturing process, you can end up with uneven doses. And because we only need the tiniest amount of LSD to experience an out-of-this-world trip, precision dosing is key.

What tends to happen is that you’ll end up applying more liquid than the paper can hold. The liquid will bead off the paper, or the paper will become too wet and can’t fully absorb the solution, which creates a lot of waste.

Laying tabs is done by taking a stack of blotter paper and soaking it fully in the liquid LSD solution. The blotters are then stored at room temperature, away from light or dust, as the solvent evaporates. It’s important for there to be excellent airflow in this area to avoid the solvents filling the air with flammable or explosive fumes.

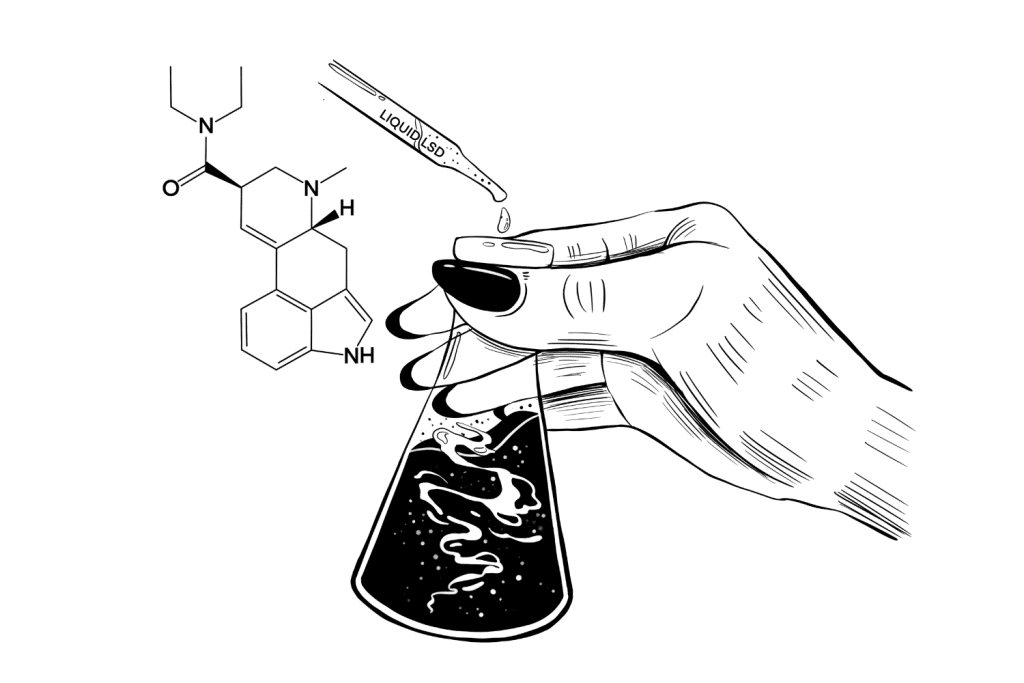

Making LSD Liquid From Blotter Paper (Volumetric Dosing)

Sometimes, you don’t want to do a full tab of acid.

While cutting a tiny piece of blotter paper in half to get the half dose seems like a logical solution, this isn’t the most accurate or the best way to split your dose of LSD.

Plus, you want to minimize how much you touch your tabs, as you could be removing and degrading the LSD potency on your fingers.

And it’s even worse of an option if you’re looking to microdose LSD to take advantage of its potential benefits for mental health, productivity, relaxation, and creativity without inducing a full-blown trip.

This is where volumetric LSD dosing comes in.

We recommend using an amber glass bottle with a dropper containing distilled water or alcohol (vodka works fine). Some people will recommend something with a higher alcohol content, like Everclear — but this will have an awful taste when you take it sublingually.

Alcohol preserves LSD better, but if you use water, make sure it’s distilled — not tap water or mineral water, as chlorine can degrade LSD.

A standard amber dropper bottle holds 1 oz (30 mL) of fluid, so fill your bottle and add three tabs to your bottle — each tab should have 100 ugs of LSD. You want to keep your bottle out of direct sunlight in a cool place for at least 48 hours before taking it.

The dropper bottles typically administer 1 mL of fluid, so you can easily calculate your dose this way.

In this instance, 1 mL will deliver 10 ugs of acid, which will be a much closer microdose than cutting a tiny tab of acid into ten pieces.

Other Forms Of LSD

LSD is one of the most popular psychedelics taken orally as blotter papers soaked in liquid LSD, which remains the most accessible method. Still, with new technologies and psychedelic use becoming more popular, you can now find other forms of LSD.

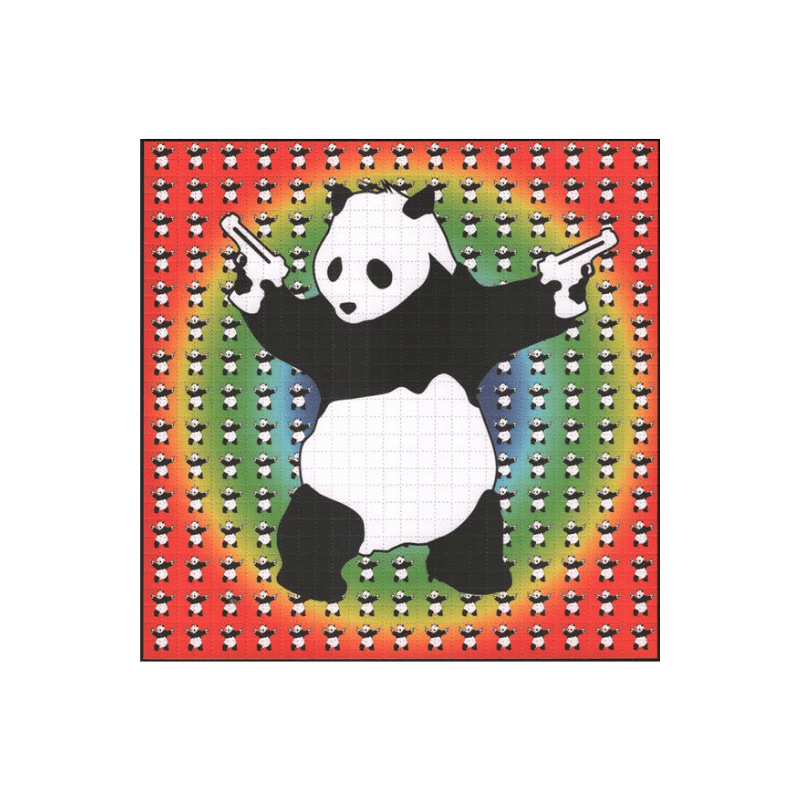

Blotter Paper

LSD blotters are absorbent papers that hold dried liquid LSD.

The paper squares are usually small and colorful and sometimes feature designs or logos printed on them.

Once the liquid has soaked into the paper and dried, the LSD-laced blotter papers are cut or perforated into small, individual doses, which are then consumed orally by placing the paper on or under the tongue, where the LSD is absorbed into the bloodstream.

Blotter papers are much easier to transport than a vial of liquid LSD, but they are sensitive to degrading quickly if they’re not handled with care. For transport and storage, blotter tabs are often wrapped in tinfoil and placed in a small baggy.

Microdots

Microdots aren’t as popular now as they were in the 60s and 70s.

They were made by taking liquid LSD and dropping it onto tiny sugar candies or gelatin cut into small round pieces. The name comes from the fact they’re so small they resemble tiny dots.

Gel Tabs

Gel tablets are newer to the scene, but they’re essentially revamped microdots of the 60s and 70s — these look like tiny pieces of Jell-O made of an LSD-infused gelatin square.

One square contains a single dose of LSD and is used the same way as conventional blotter tabs.

One of the advantages of these gel tabs is that they can hold higher doses of LSD — up to five times more than paper.

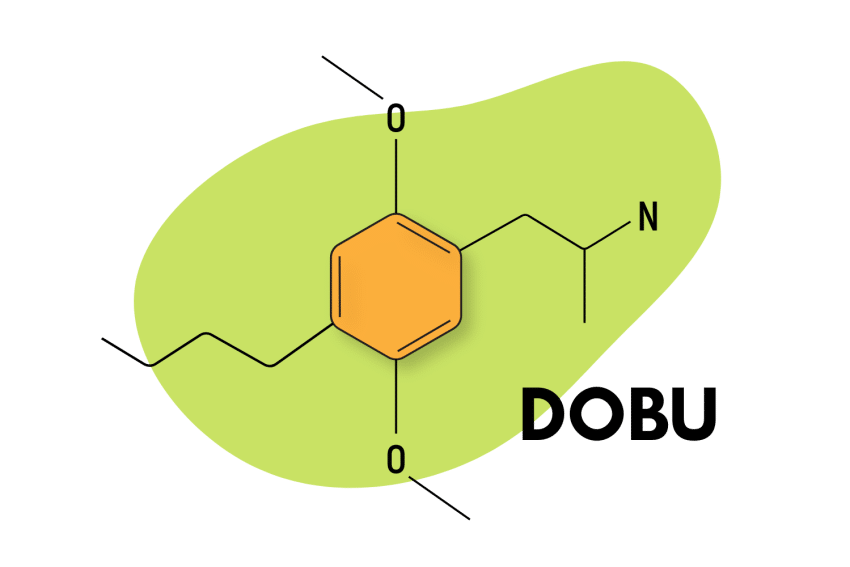

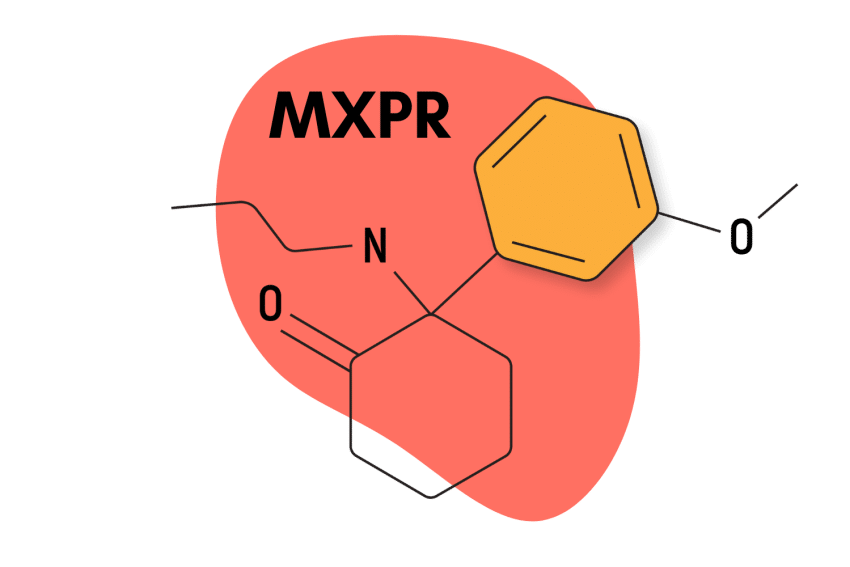

LSD-Alternatives Also Come in Liquid Form

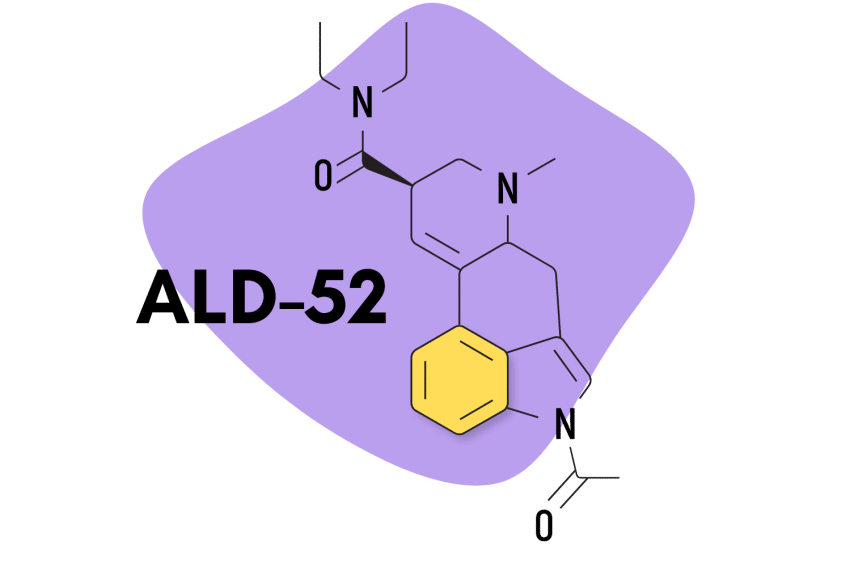

LSD is one of the many related compounds in the lysergamide family of drugs. Just about all of them come in blotter paper, gel tab, microdot, or liquid form.

Most of these substances share similar effects and dosage recommendations with LSD — but have their own unique psychedelic “flavor.”

Some popular examples include AL-LAD, PRO-LAD, ETH-LAD, 1P-LSD, ALD-52, LSZ, and PARGY-LAD.

LSD 101: Benefits, Risks, & Legal Status

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD, acid, Lucy, or yellow sunshine) is a synthetic drug accidentally discovered by a Swiss chemist, Albert Hofmann, in the 1930s while working with a fungus that grows on rye grains (Claviceps purpurea).

Nearly two decades after its discovery, it was refined into a pharmaceutical drug named “Delysid” by Sandoz Laboratories and used in a clinical setting for neuroses, alcoholism, and to enhance creativity [1].

While the drug showed much promise for supporting mental health conditions, it was eventually banned in the 1960s because of its association with government conspiracies and the rise of the United States counterculture movement.

Due to its controversial history, it was categorized as a Schedule I drug in the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Despite its past, LSD has since made a comeback in the psychedelic renaissance for its therapeutic potential for depression, alcoholism, post-traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Why You Should Test Your LSD

Pure LSD has decades of research to prove it’s non-toxic and not physically addictive; the issue is that LSD remains illegal in most countries, and sourcing a safe supply of LSD on the black market is a bit of a gamble since there is no standardization.

Testing your psychedelics before taking them is part of responsible drug use as it can help to reduce the risk of accidental overdose or adverse effects.

There are various testing methods for LSD, including test kits that use reagents to detect the presence of LSD or other tryptamines in a sample.

With blotters, the primary contaminant you’re on the lookout for is NBOMe substances, which have a similar potency to LSD but are much more dangerous.

With liquid LSD, the risk is much higher. Anything could be dissolved in solution, so it’s essential for users to test before assuming their liquid is pure.

The first test, using the Ehrlich reagent, will determine if an indole alkaloid is present (such as LSD, DMT, or psilocybin).

The Hofmann reagent is then used to differentiate LSD from other tryptamines like DMT or psilocybin.

The Mecke reagent will rule out more dangerous substances like opiates, and the Mandelin reagent can help rule out other psychedelics such as ketamine or other arylcyclohexylamines.

There are other forms of lysergamides, some of which may be stronger than what you expect with an acid tab, so it’s worth getting your drugs tested before taking them.

The Importance Of Set And Setting For Your Trip

Set and setting are important factors to consider when embarking on a psychedelic trip, as they can impact the quality of your experience.

The “set” is the internal factor of your trip. It’s the mood, mindset, and emotional state you’re in. Psychedelics like LSD tend to intensify your current emotions, so going in with a positive mindset helps ensure you have an enjoyable trip.

“Setting” refers to the physical environment of your trip. Choose a safe, comfortable, and familiar setting that puts you at ease. A peaceful environment can help reduce feelings of anxiety.

If it’s your first psychedelic trip, you may want to consider a trip sitter who is in charge of maintaining a safe environment for the duration of the trip.

Related Article: Tripsitter Safe Tripping Guidelines

Frequently Asked Questions

Let’s answer some of our most commonly asked questions about liquid LSD…

1. What does liquid acid taste like?

The crystals of LSD don’t have a flavor or scent of their own. If there is a flavor, it’ll be from whatever solvent was used.

2. How long does it take for liquid acid to kick in?

Most people will start to feel the effects of a standard dose of liquid acid within 10–40 minutes after taking it, with peak effects around the 3–4 hour mark.

3. How long do the effects of liquid LSD last?

The length of your trip can depend on the dose and your individual body chemistry. A full LSD dose typically lasts around 10–12 hours, but the intensity of hallucinogenic effects should dissipate after 8–9 hours.

4. Can you build a tolerance to LSD?

It’s possible to build a tolerance to LSD with consistent use, and it builds up very quickly. But it’s not physically addictive — likely because it is so easy to build tolerance.

Tolerance refers to how fast the body builds resistance to the same drug dose, producing a weaker effect.

LSD tolerance is not the same as the tolerance one builds to opioids and alcohol, where taking more of the substance is needed to achieve the same effects. With LSD, taking more doesn’t necessarily increase the intensity of the experiences. In most cases, it ends up being a waste because you might not feel anything at all.

5. What happens if you take too much LSD?

If you accidentally take too much LSD, you’re in for an intense trip — but thankfully, it’s a non-toxic compound. It might feel very intense, and you’ve no choice but to ride out the waves until the drug has run its course through your system.

6. Is it true that tap water neutralizes LSD?

The jury is out on this one, but many experts will advise you to avoid drinking tap water when taking LSD for at least an hour after ingesting it if you want to strongest effects. The idea is that the chlorine in tap water can neutralize some of the psychoactive effects of LSD. We’ve used tap water with our LSD without any problems in the past, but our tap water might contain less chlorine than yours. To be safe, we advise using filtered or distilled water if available.

7. What are the pros and cons of liquid LSD?

The pros of liquid LSD are cost-efficiency (it’s usually cheaper to order LSD liquid in bulk than individual tabs), more versatility (you can make tabs, mix with sugar or water, etc.), and a much longer shelf-life than blotter squares.

The cons are cost (the upfront cost can be very high) and the fact that it’s very easy to accidentally dose too much.

References

- Novak, S. J. (1997). LSD before Leary: Sidney Cohen’s critique of 1950s psychedelic drug research. Isis, 88(1), 87-110.

- Suzuki, O., Watanabe, K., & Suzuki, S. (2005). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Drugs and Poisons in Humans: A Handbook of Practical Analysis, 225-228.