Valium: What to Know & How to Stay Safe

Diazepam — sold under the brand name Valium — is a prescription benzodiazepine drug for managing anxiety-related disorders.

To a more limited degree, diazepam is also approved as a valuable adjunct for relieving skeletal muscle spasms and a treatment for acute alcohol withdrawal and convulsive disorders.

Many people use diazepam off-label (for purposes not approved by the FDA). Some use it for treating conditions such as insomnia, restless leg syndrome and as a recreational drug for its euphoric and intoxicating effects [1].

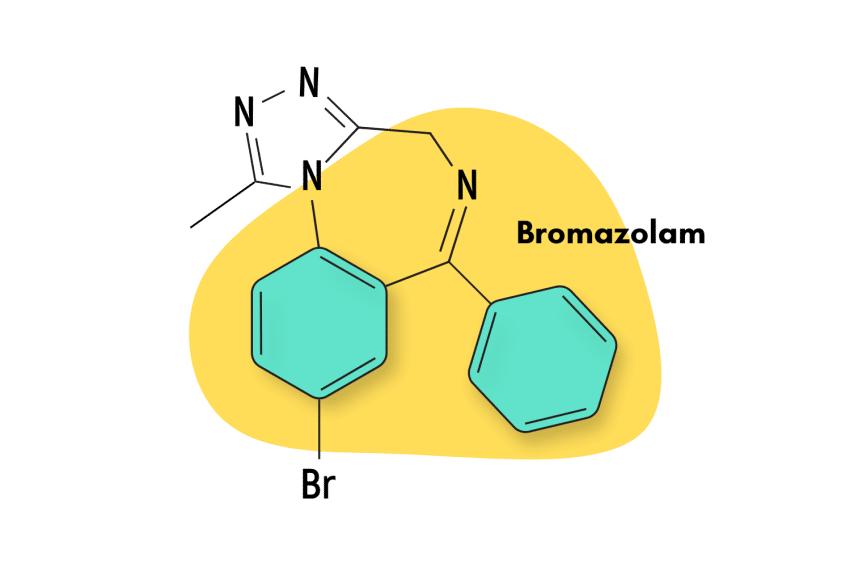

Diazepam is classified as a 1,4-benzodiazepine, which makes it closely related to other popular benzodiazepines, including clonazepam (Klonopin), lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), phenazepam (Phenazepam), and many others.

Here, we’ll examine diazepam’s effects, cover important safety and harm reduction information, and compare diazepam to other popular benzodiazepine derivatives and natural alternatives.

Diazepam Specs

| Status | Approved 💊 |

| Common Dosage | 5–25 mg |

| PubChem ID | 3106 |

| CAS# | 439-14-5 |

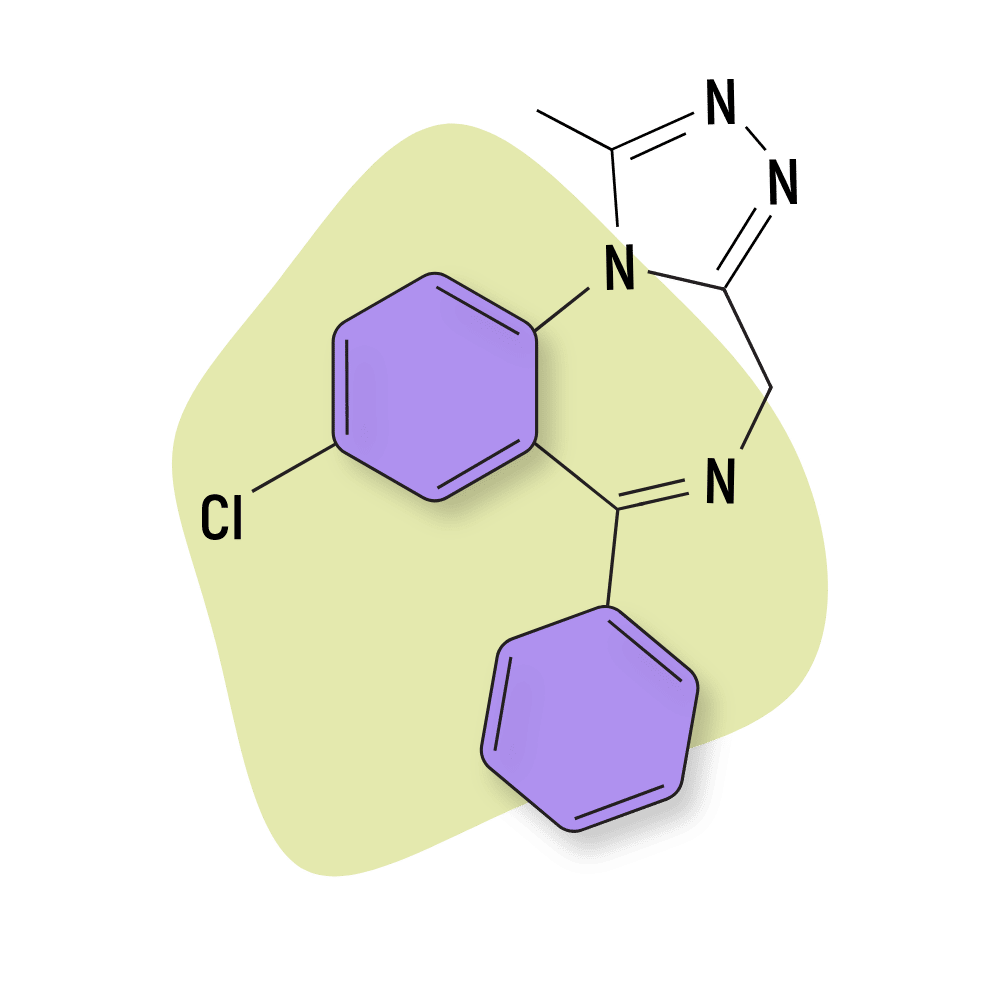

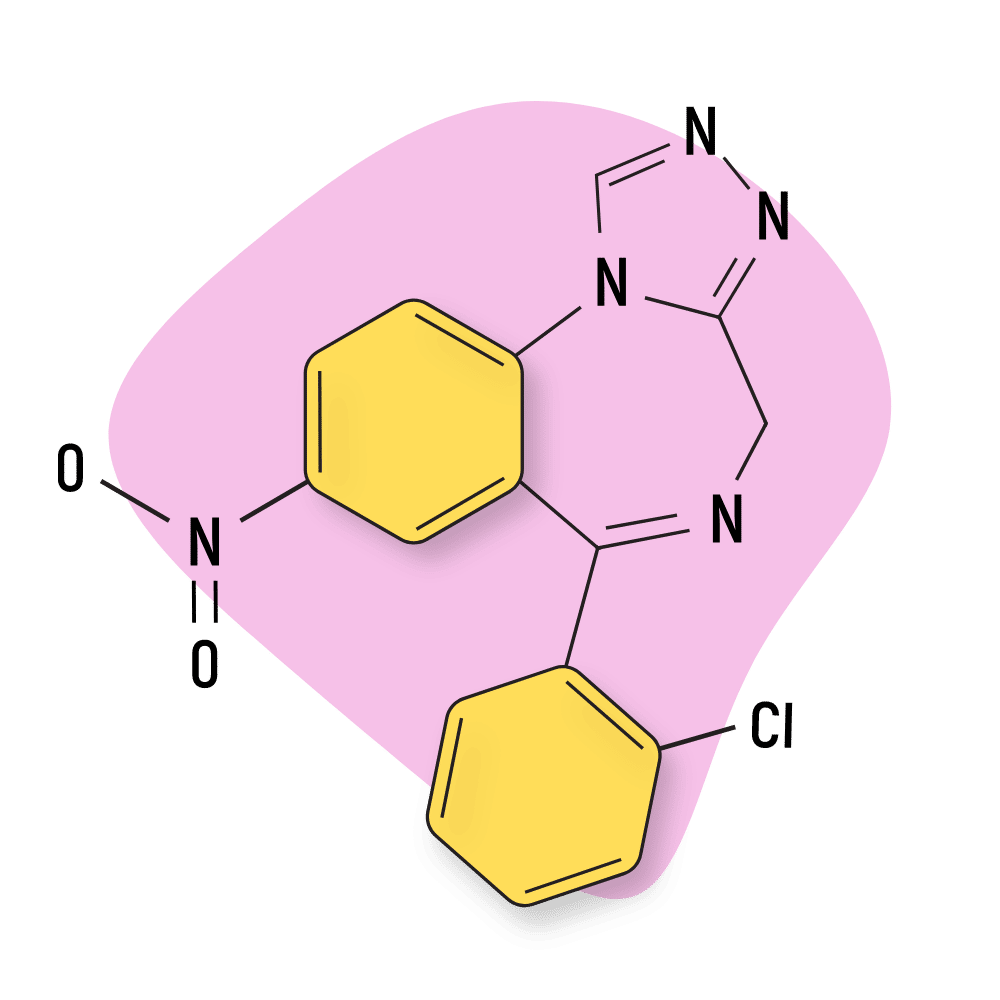

IUPAC Name: 7-chloro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-3H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one

Other Names: Antenex, Apaurin, Apzepam, Apozepam, Diazepan, Hexalid, Normabel, Pax, Stesolid, Stedon, Tranquirit, Valium, Vival, Valaxona

Metabolism

Diazepam is N-demethylated by CYP3A4 and 2C19 to the active metabolite N-desmethyldiazepam and is hydroxylated by CYP3A4 to the active metabolite temazepam.

Duration of Effects

Long-Acting (10–36 hours). Diazepam is long-lasting, with a duration of action of more than 12 hours.

How Strong is Diazepam?

Diazepam is considered about average in terms of dose. Other medications like triazolam (Halcion) or alprazolam (Xanax) are more potent. These drugs are active in doses below a single milligram. Other medications, such as flurazepam (Dalmadorm) or halazepam (Paxipam), are much weaker.

Diazepam is often used as the baseline when comparing the potency of benzodiazepine drugs. Other drugs are assessed by comparing their equivalent dose to 10 mg of diazepam.

Benzodiazepine Dosage Equivalency Calculator

**Caution:** Benzodiazepines have a narrow therapeutic window. Dose equivalents may not be accurate in higher doses.

This calculator does not substitute for clinical experience and is meant to serve only as a reference for determining oral benzodiazepine equivalence.

Please consult a medical practitioner before taking benzodiazepines.

Diazepam Dosages

Proper dosage will always be one of the critical factors in reducing risk. However, when you take into account all of the possible factors like body weight, indication, method of administration, and more, the proper dosage can start to become more complicated, and that’s why it’s crucial to always use your diazepam in strict accordance with your prescription.

According to the Mayo Clinic, these are proper dosages for diazepam (oral solution or tablets) include:

| Indication | Adults | Older Adults | Children (six months and older) | Children (up to six months |

| Anxiety | 2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 2 to 4 times a day | At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed | At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed | Use is not recommended |

| Alcohol Withdrawal | 10 milligrams (mg) 3 or 4 times for the first 24 hours, then 5 mg 3 to 4 times per day as needed | At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor will gradually increase your dose as needed | Your doctor must determine use and dose | N/A |

| Muscle Spasms | 2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 3 or 4 times a day | At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed | At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed | Use is not recommended |

| Seizures | 2 to 10 milligrams (mg) 2 to 4 times a day | At first, 2 to 2.5 mg 1 or 2 times a day. Your doctor may increase your dose if needed | At first, 1 to 2.5 mg 3 or 4 times per day. Your child’s doctor may increase the dose if needed | Use is not recommended |

How Does Diazepam Work?

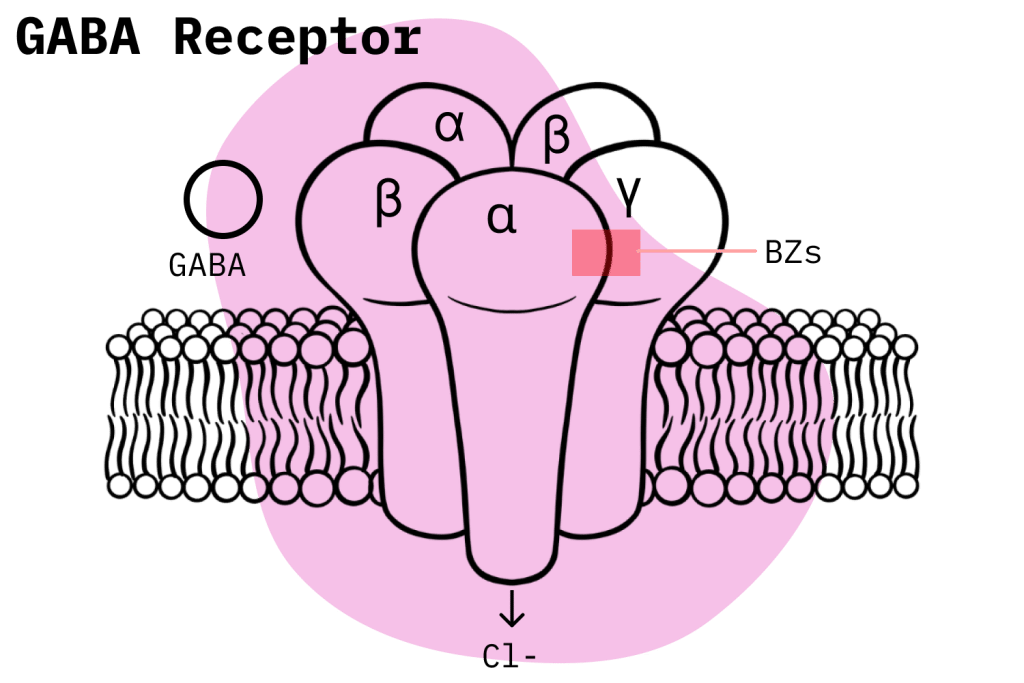

As a classical benzodiazepine — diazepam’s effects are mainly carried about by its action as a positive allosteric modulator for the GABA-A receptor [1].

GABA is the body’s primary neuroinhibitory molecule — it essentially acts like the brake pedal for the brain. When we experience stress and anxiety, GABA is used to slow electrical activity in the brain to slow us down and eliminate anxious thought patterns. The same is true during the evening as the body prepares the mind to fall asleep.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam force GABA to have a more substantial effect of inducing these states of calmness and tranquility. This action allows diazepam (and other benzos) to stop anxiety attacks in their tracks, cause the muscles to relax, and coax the mind to prepare for sleep.

All classical benzodiazepines share this exact mechanism of action. But diazepam also has some unique characteristics that differentiate it from other members of its class.

For example, there’s evidence suggesting that diazepam also binds to voltage-gated sodium channels and might contribute to some of its anticonvulsant properties [2].

Other studies suggest diazepam can also bind to a unique benzodiazepine receptor located on the mitochondrial membrane known as the “translocator protein (18 kDa)” [3].

Regarding its characteristics among the vast number of available benzodiazepines, diazepam’s potency, high bioavailability, and fast onset of action largely account for its clinical efficacy and commercial success.

Is Diazepam Safe? Risks & Side Effects

Diazepam, like all benzodiazepines, carries an inherent risk of developing physical and mental dependence. Withdrawal symptoms can become quite severe and, in rare cases, even become fatal. This risk accounts for diazepam’s classification as a Schedule IV medication under the Controlled Substances Act, but—in reality—the danger can be a lot more pervasive.

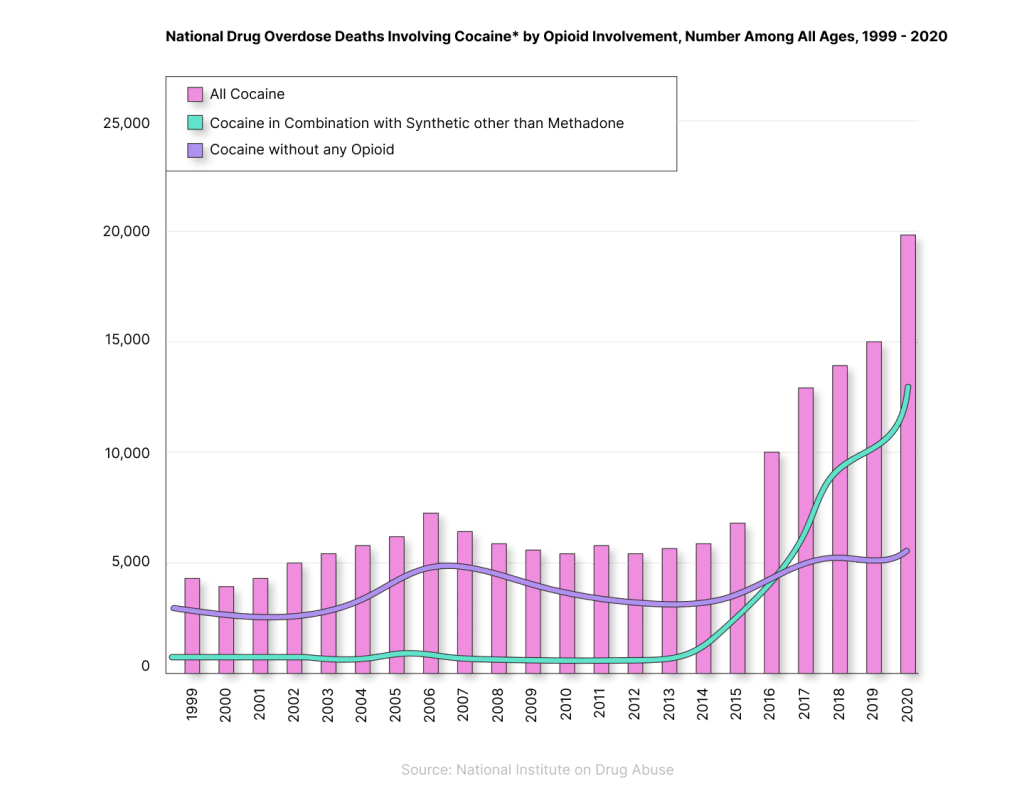

Recent trends in overdose fatalities and benzodiazepine misuse in the United States should be a grave cause for concern to anyone considering a possible benzodiazepine prescription. There is now a solid argument that a smaller but still significant benzodiazepine crisis has developed alongside the ongoing opioid epidemic.

A recent National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) study reveals some worrying statistics: 16% of opioid overdose deaths also involve benzodiazepine use. A 2020 survey by the CDC helps put these numbers in context; it showed how benzodiazepines were involved in a total of 12,190 deaths in the United States.

If we step back and look at the larger trend over the past twenty years, it becomes quite clear how benzodiazepine misuse has steadily risen since 1999.

For example, a graph put together by NIDA (shown below) illustrates the rise in deaths associated with benzodiazepine drugs over the past ten years.

An interesting fact to note is how fatalities involving benzodiazepines started to plateau in 2010, but when the opioid crisis kicked off in 2014, they began climbing once again. The trend shows how polydrug abuse is usually a significant contributing factor in drug fatalities.

When it comes to diazepam specifically, it is not easy to draw meaningful conclusions about the role individual benzodiazepines play in terms of their abuse potential and how they factor into the larger crisis. There are many reasons for this. For example, drug intoxication exams are usually not specific enough to determine which exact benzodiazepines are present in drug overdose deaths. Nevertheless, there are still some conclusions to be had.

Since diazepam is the fourth most prescribed benzodiazepine in the United States, comprising around 11% of prescriptions, it can be reasonably inferred that it contributes significantly to benzodiazepine misuse statistics and events. We can back up this generalized statement with some clinical evidence.

It is theorized that pharmacokinetic differences play an important role in the differences in abuse potential between benzodiazepines. In this sense, various chemical properties related to diazepam, in addition to medical experience and drug user testimony, point to diazepam as having a high potential for abuse [4]. For instance, the potent high and fast onset of effects related to diazepam is reported as a major cause of abuse. However, alprazolam and clonazepam, the #1 and #2 most prescribed benzodiazepines, respectively, still account for most ED (Emergency Department) visits [5].

Side Effects of Diazepam

As with all other benzodiazepines, diazepam’s most common side effects are drowsiness, fatigue, and muscle weakness.

According to the FDA, the following adverse effects of diazepam have been officially identified:

- Antegrade amnesia

- Anxiety

- Blurred vision

- Changes in libido

- Changes in salivation

- Confusion

- Constipation

- Depression

- Diplopia

- Dizziness

- Drowsiness

- Dysarthria

- Elevated transaminases and alkaline phosphatase

- Fatigue

- Gastrointestinal disturbances

- Hallucinations

- Headache

- Hypotension

- Incontinence

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Muscle weakness

- Nausea

- Skin reactions

- Slurred speech

- Tremors

- Urinary retention

- Vertigo

Benzodiazepine Withdrawal & Dependence

It’s widely recognized that benzodiazepine use can induce physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms in users. In the medical world, it is also common knowledge that the most dangerous drug withdrawal symptoms are related to benzodiazepines, alcohol, and opiates.

To minimize the risk stemming from physical dependence, it’s standard practice for doctors to assign benzodiazepine treatment for the shortest time frame possible, usually around four weeks. However, if physical dependence does develop, the sudden discontinuation of benzodiazepines, even after four weeks, can provoke severe withdrawal symptoms. In such cases, a slow drug tapering process is required to safely get off benzodiazepines. This can take as long as 24 weeks.

Anyone considering a benzodiazepine prescription should seriously consider the risks involved in dependence, as the preponderance of users who develop symptoms is not trivial. In this study, one-third of individuals who used benzodiazepines for longer than four weeks became physically dependent after concluding treatment [6].

When it comes to diazepam, its relatively long elimination half-life makes it less likely that it will produce withdrawal symptoms in users [7].

Harm Reduction Tips: Diazepam

Here are some tips and tricks for staying safe while using benzodiazepine drugs:

- 🥣 Don’t mix — Mixing benzodiazepines with other depressants (alcohol, GHB, phenibut, barbiturates, opiates) can be fatal.

- ⏳ Take frequent breaks or plan for a short treatment span — Benzodiazepines can form dependence quickly, so it’s important to stop using the drug periodically.

- 🥄 Always stick to the proper dose — The dosage of benzos can vary substantially. Some drugs require 20 or 30 mg; others can be fatal in doses as low as 3 mg.

- 💊 Be aware of contraindications — Benzodiazepines are significantly more dangerous in older people or those with certain medical conditions.

- 🧪 Test your drugs — If ordering benzos from unregistered vendors (online or street vendors), order a benzo test kit to ensure your pills contain what you think they do.

- 💉 Never snort or inject benzos — Not only does this provide no advantage, but it’s also extremely dangerous. Benzos should be taken orally.

- 🌧 Recognize the signs of addiction — Early warning signs are feeling like you’re not “yourself” without the drug or hiding your habits from loved ones.

- ⚖️ Understand the laws where you live — In most parts of the world, benzodiazepines are only considered legal if given a prescription by a medical doctor.

- 📞 Know where to go if you need help — Help is available for benzodiazepine addiction; you just have to ask for it. Look up “addiction hotline” for more information where you live. (USA: 1-800-662-4357; Canada: 1-866-585-0445; UK: 0300-999-1212).

General harm reduction recommendations for diazepam might appear obvious, but at the same time, they are the most effective at reducing risk.

In general terms, users should avoid benzodiazepine misuse through the responsible use of a legitimate prescription. If you have a history of abuse with regard to alcohol or drugs, then you are much more likely to engage in misuse if you acquire a benzodiazepine prescription. Most serious health events related to benzodiazepines happen because of misuse.

However, even if there’s no misuse, users could still wind up developing physical dependence symptoms, which is why it’s extremely important to weigh the risks against the benefits before seeking out a benzodiazepine prescription. The smart move is to try out non-pharmacological options beforehand.

Diazepam Drug Interactions

Recent trends in misuse have revealed the immense dangers of abusing benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants like opioids, GHB, phenibut, barbiturates, and alcohol.

Users should avoid all recreational drug use but should take special precautions regarding the concomitant use of CNS depressants. Research has shown that this combination has a high potential to cause respiratory depression: the leading cause of death in drug overdoses.

This combination has become such a prevalent issue that the FDA has issued several warnings about it, including a box warning.

Users should also be aware of CYP drug interactions that might affect the proper metabolization of diazepam within the body. CYP inhibitors and inducers can, respectively, slow down clearance to the point diazepam starts building up in the body, leading to increased risk, or they can speed up the clearance and thus make the drug less effective. Diazepam is largely metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzymes, which are also responsible for metabolizing more than 50% of all prescription drugs currently on the market [10]. This means many other prescription medications could indirectly result in side effects if used in conjunction with diazepam.

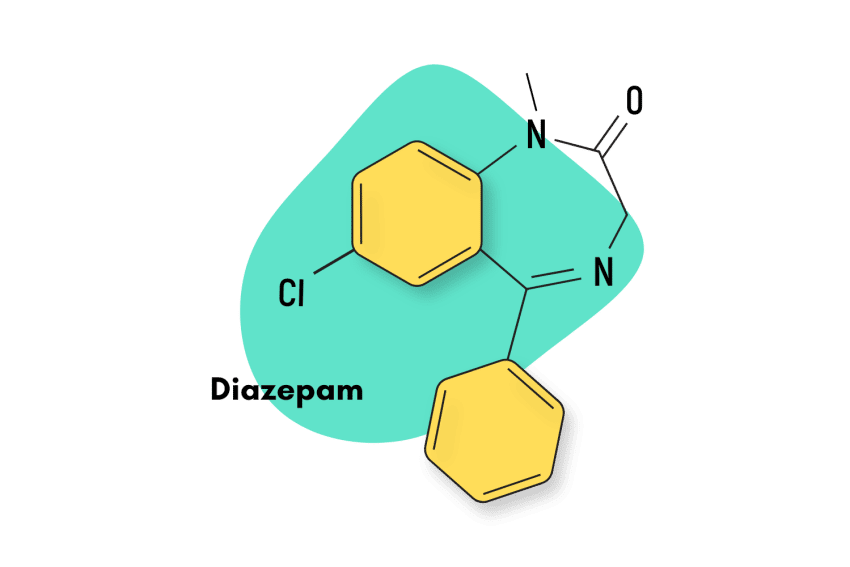

Similar Benzodiazepines

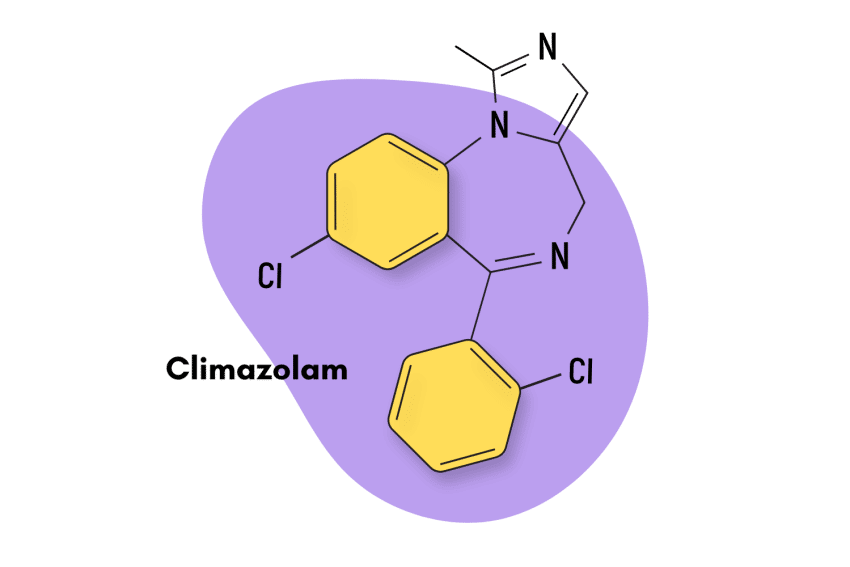

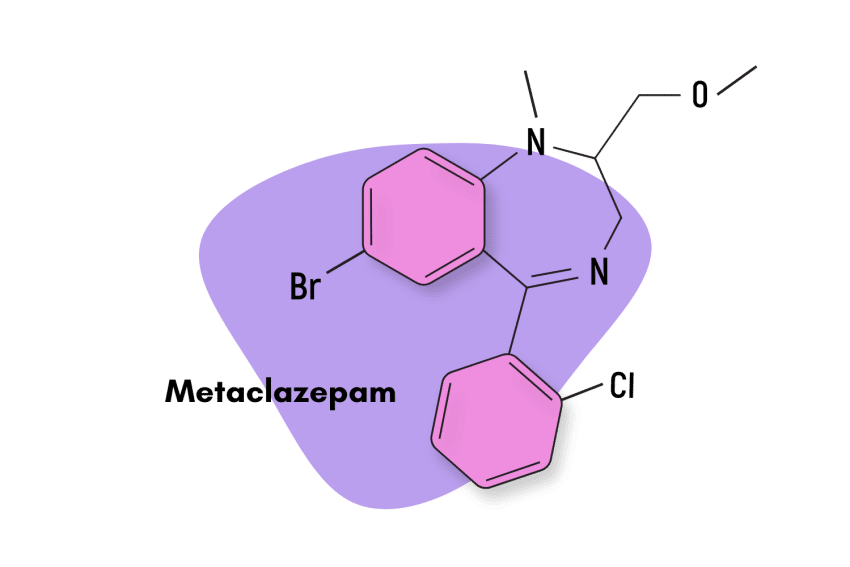

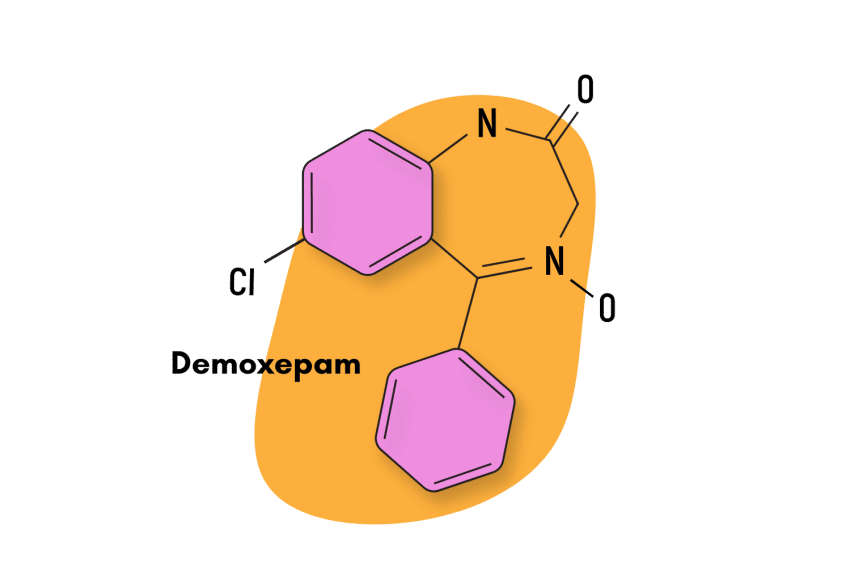

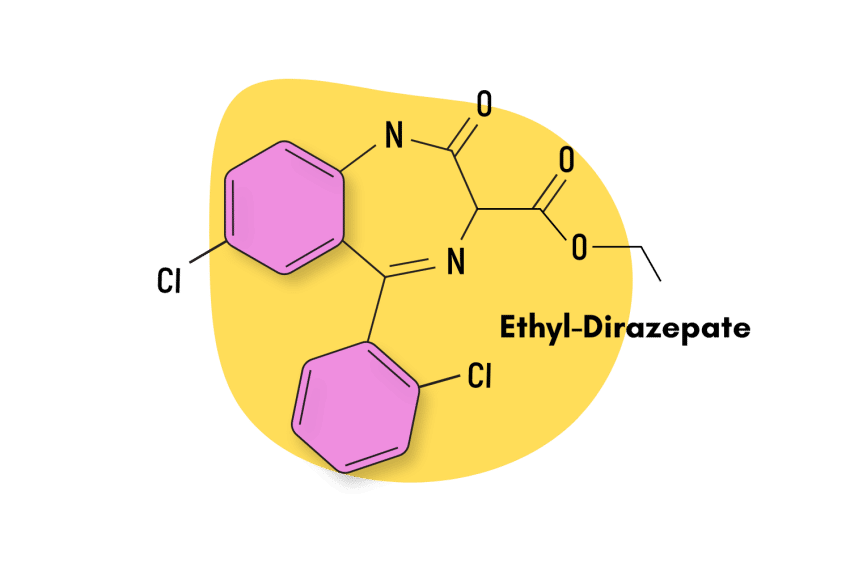

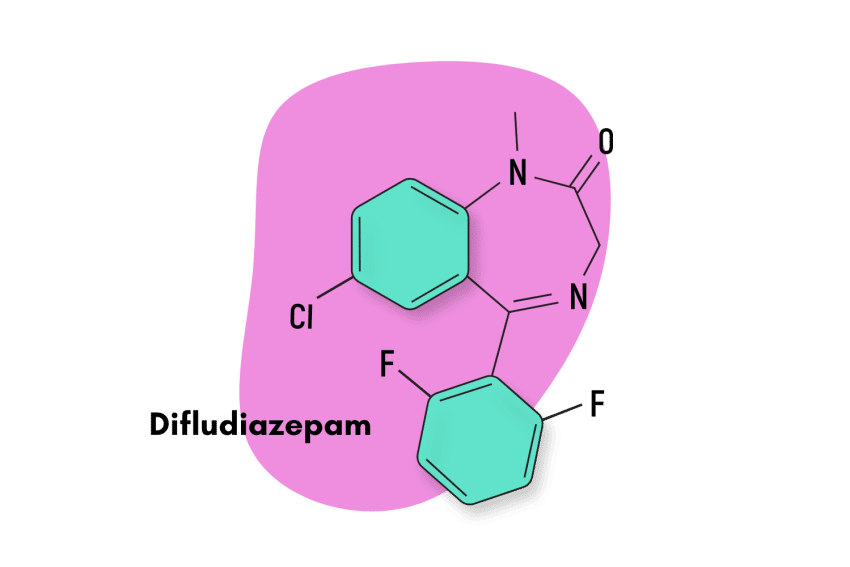

Diazepam is considered the “standard” benzodiazepine. It’s the simplest member of the group from which all other benzodiazepines are built. The very definition of a benzodiazepine is a benzene ring fused to a diazepine ring.

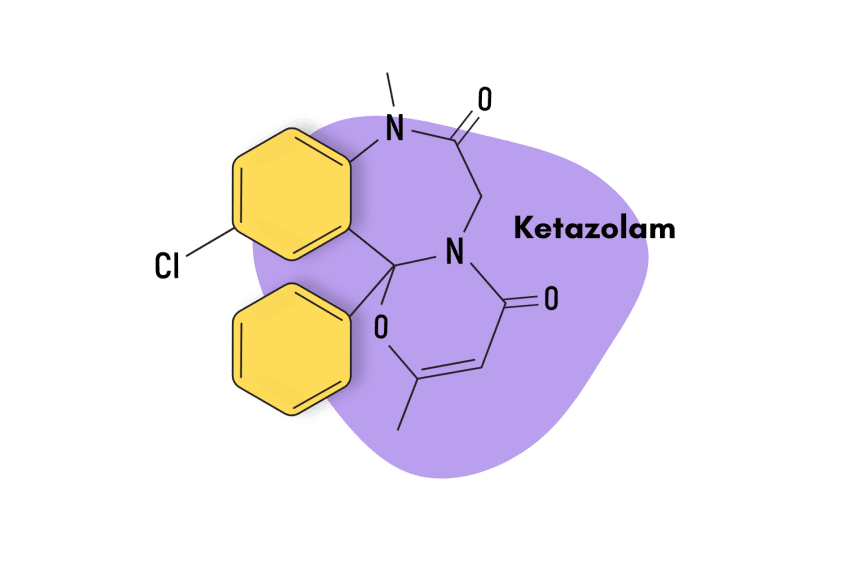

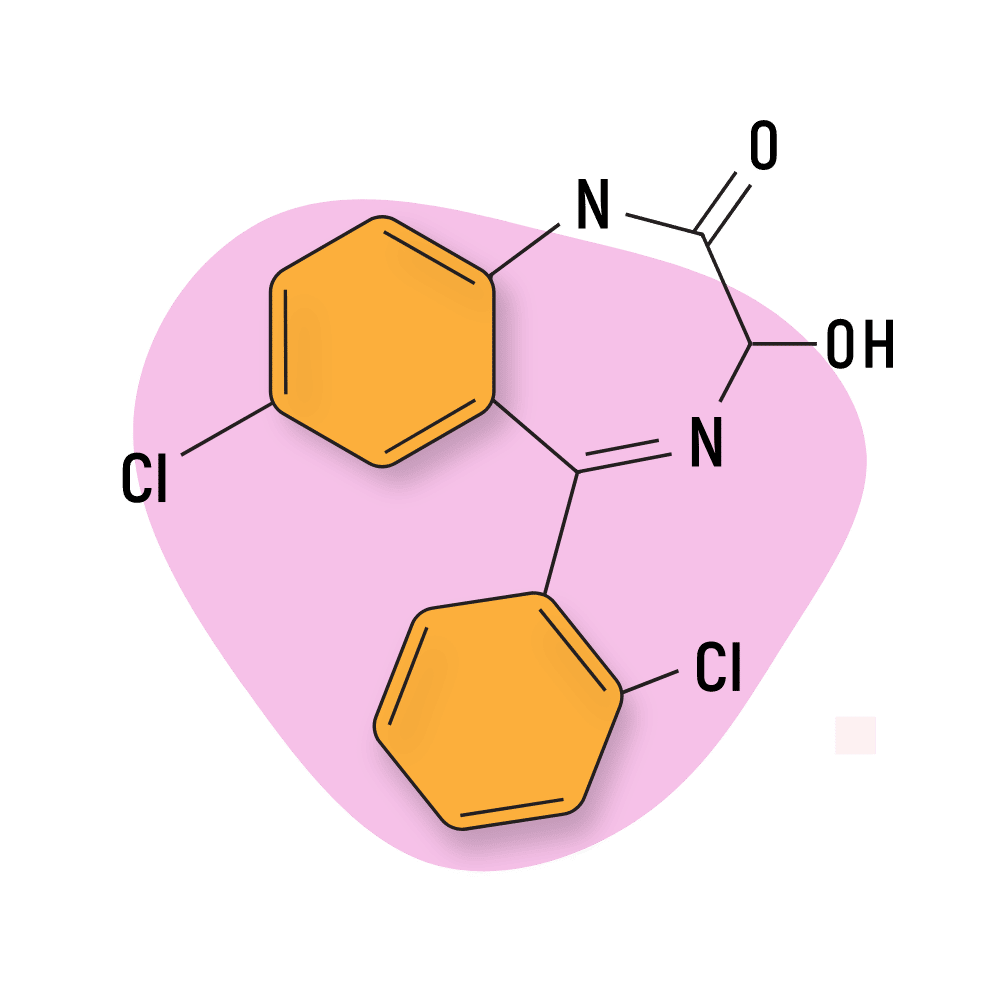

Regarding specific qualities, diazepam is a long-acting, 1,4-benzodiazepine with about average potency. Other drugs that fit this description include chlordiazepoxide (Librium), halazepam (Paxipam), ketazolam (Anseren), and phenazepam (Phenazepam).

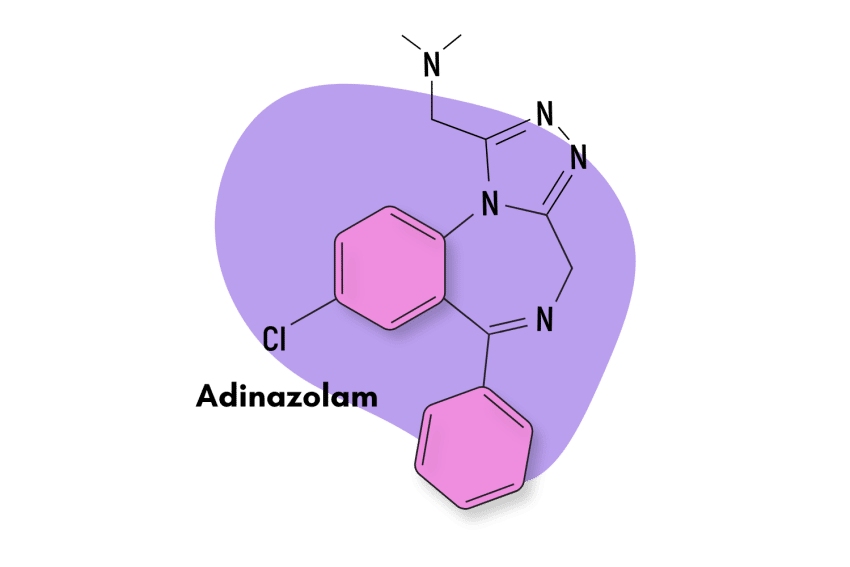

In terms of effects, drugs like alprazolam (Xanax), clonazolam (Klonopin), lorazepam (Ativan), etizolam, bromazepam (Lectopam), and bretazenil are all decent alternatives.

Let’s cover some of the alternatives that share the most in common with diazepam in terms of effects:

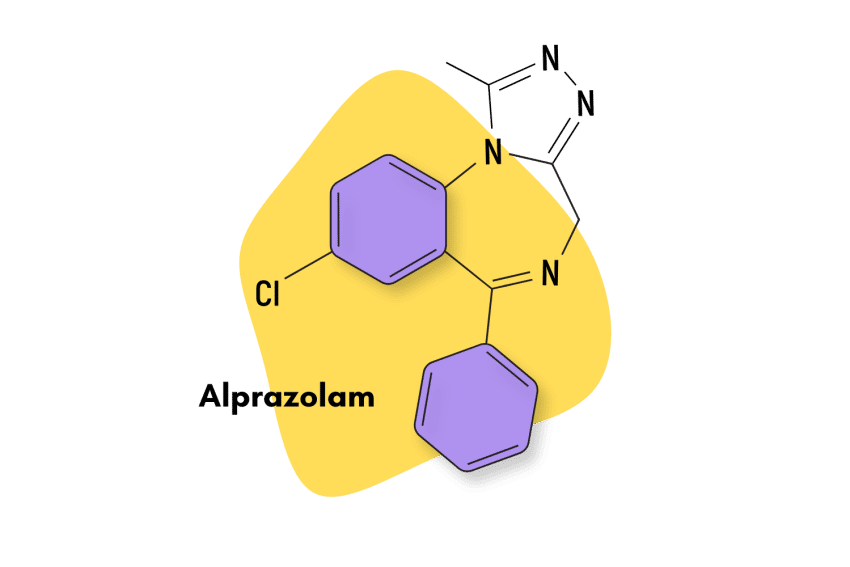

Alprazolam (Xanax)

Despite having meaningful differences, alprazolam — sold commercially as Xanax — has many similarities with diazepam.

Both of these benzodiazepines are commercially successful and are indicated for the treatment of anxiety-related disorders. They’re also both popular options among recreational users.

Meaningful differences between alprazolam and diazepam include onset times (alprazolam takes longer to kick in), duration of effects (alprazolam doesn’t last as long), and potency (alprazolam is significantly stronger than diazepam).

Clonazolam (Klonopin)

Klonopin is another classical 1,4-benzodiazepine that, like diazepam, has achieved great market popularity. Generally speaking, both compounds are quite similar, but there are certain differences that users should be aware of.

For instance, Klonopin is vastly more potent than diazepam, with 0.75 mg being roughly equal to 10 mg of diazepam. Diazepam is longer-lasting, too, with an elimination half-life of 24-36 hours. Klonopin has one of 9.5 to 30 hours.

Lastly, these compounds also have different indications. Diazepam is best at managing anxiety, while Klonopin is indicated for panic disorders (a more extreme form of anxiety).

Lorazepam (Ativan)

Lorazepam, also known as Ativan, is one of the most effective benzodiazepines in the world and is utilized for basically all of the traditional benzodiazepine-related treatments like insomnia, anxiety, muscle tension, etc.

It’s largely comparable to diazepam, but some differences stand out. Namely, Ativan is more potent and has a short duration of effects.

Natural Alternatives to Benzodiazepines

In the last couple of years, several plant-based, non-pharmaceutical alternatives have gained prominence as people become more educated about the downsides of prescription benzodiazepines and their potential for addiction.

There are several plants and a few nutrients that may serve as viable alternatives for many people — but it’s important to note that natural products aren’t going to be as strong as concentrated synthetic molecules. This is a double-edged sword because this reduced potency also comes with substantially higher safety levels.

One of the best natural alternatives to benzodiazepines is the kava plant (Piper methysticum), which contains a series of active ingredients called kavalactones. Many of these compounds work through the same mechanism of action as benzos — they bind and modulate the body’s GABA receptors to produce a marked relaxant and sedative action.

Other useful herbs with similar effects include valerian, chamomile, and L-theanine (one of the active ingredients in green tea).

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is another excellent option for providing anxiety and sleep support (when used in higher doses). Unlike the other herbs on this list, kratom only has a minor impact on GABA. It works instead by interacting with glutamate, dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, but the end results are very similar.

Diazepam FAQs

What formulations is diazepam available in?

As Valium, diazepam is available in oral administration tables containing either 2 mg, 5 mg, or 10 mg of diazepam.

Does diazepam have high bioavailability?

Yes, after oral administration,>90% of diazepam is absorbed.

How long is diazepam’s elimination half-life?

Diazepam has a long elimination half of around 24-48 hours. The terminal elimination half-life of the active metabolite N-desmethyldiazepam is up to 100 hours [1].

References

- Calcaterra, N. E., & Barrow, J. C. (2014). Classics in chemical neuroscience: diazepam (Valium). ACS chemical neuroscience, 5(4), 253-260.

- Willow, M., Kuenzel, E. A., & Catterall, W. A. (1984). Inhibition of voltage-sensitive sodium channels in neuroblastoma cells and synaptosomes by the anticonvulsant drugs diphenylhydantoin and carbamazepine. Molecular pharmacology, 25(2), 228-234.

- Papadopoulos, V., Baraldi, M., Guilarte, T. R., Knudsen, T. B., Lacapère, J. J., Lindemann, P., … & Gavish, M. (2006). Translocator protein (18 kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 27(8), 402-409.

- Griffiths, R. R., & Wolf, B. (1990). Relative abuse liability of different benzodiazepines in drug abusers. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology.

- Schmitz, A. (2016). Benzodiazepine use, misuse, and abuse: a review. Mental Health Clinician, 6(3), 120-126.

- Riss, J., Cloyd, J ., Gates, J., & Collins, S. (2008). Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Acta neurologica scandinavica, 118(2), 69-86.

- Weintraub, S. J. (2017). Diazepam in the treatment of moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal. CNS drugs, 31(2), 87-95.

- Cairney, S., Clough, A. R., Maruff, P., Collie, A., Currie, B. J., & Currie, J. (2003). Saccade and cognitive function in chronic kava users. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(2), 389-396.

- Swogger, M. T., & Walsh, Z. (2018). Kratom use and mental health: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 134-140.

- Williams, J. A., Ring, B. J., Cantrell, V. E., Jones, D. R., Eckstein, J., Ruterbories, K., … & Wrighton, S. A. (2002). Comparative metabolic capabilities of CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 30(8), 883-891.